Racial Dilemna

African-American soldiers in the Spanish American War, 1898. Photo courtesy of LEARN NC, all rights reserved.

Perhaps the most interesting topic that is covered in the Spencer Collection is how race is discussed in wartime. Whenever a country has deep roots of prejudice about one race it takes hundreds of years and several progressive generations of citizens to allow acceptance. Another way to expedite this process is through the shared experience of combat. One impact of allowing African American soldiers into the army in the Civil War was a greater sense of self worth among those that served. They had fought and died beside their white brethren, and their courage and poise under fire could no longer be questioned. For a short time after the Civil War ended, the Reconstruction era went well for African Americans. Unfortunately, politics and racism derailed most of this progress so when the Spanish American War and First World War arrived, race relations had not changed much since the Civil War.

What makes the music fascinating during this time is that roughly half of the songs are in favor of letting African American soldiers fight for their country while the other half mock the supposed ineptitude and laziness of these same soldiers. This insight reveals a country that was still deeply divided over race, a topic that this country is still addressing to this day.

This song, composed by Harry DeCosta in 1918, is strongly in favor of allowing African American soldiers to fight for their country. A common theme in early African American culture was to reference how God would not judge a person based on their skin and the title of this song appeals to that sentiment.

Also noteworthy is the first line of the chorus which claims that, “Your Granddad did his duty in the Civil War he fell by his master’s side.” While songs such as this were progressive for their time, many would still have offhand remarks about the social stratification that was prevalent in the United States. African American soldiers who fought for the North in the Civil War were all free men and certainly did not have a master. While there is some evidence to support the fact that blacks fought for the Confederacy, their numbers were vastly smaller and rarely served as “official” soldiers.

Offensive cover art aside, this song composed by Harry Carroll in 1918 is another example of the songwriter happy with the idea of African American soldiers fighting for freedom and the opportunity to, “Give the whole world liberty, just like Lincoln did for me.”

It is ironic the song claims that Dixie will be proud of their old black Joe, especially because the protagonist claims to have fought in the Civil War for the North in 1861 and gained his freedom from people that wanted him enslaved.

You’ll Find Old Dixieland in France was composed by George Meyer in 1918 and is a perfect example of a song being simultaneously sympathetic and racist towards African Americans. It is perhaps best encapsulated in the line, “Instead of pickin’ melons off the vine, they’re picking Germans off the Rhine.”

This duality expressed by white American citizens (being happy that African Americans are fighting for their country while also perpetuating harmful stereotypes of these same soldiers) is indicative of the struggles faced by African Americans for hundreds of years.

Jigadeer Johnson was composed by Seneca Lewis in 1918. Described as a “comic” song, it relies heavily on racist phrases and stereotypes such as the myth of the lazy “Sambo” character. These characters were heavily used in minstrel shows and some of these stereotypes can, regrettably, be seen in modern culture as well.

Henry Murtagh composed this song in 1918. Private “Stonewall Jackson Lee,” an obvious reference to the two most well-known Confederate Generals of the Civil War, is accused of falling asleep on duty, another allusion to the lazy Sambo stereotype. The song continues its parade of ignorance by claiming the soldier was thinking of all the Christmas gifts he would be receiving, such as a trombone and watermelon.

Songs such as these reveal the contradictory relationship between African Americans and their fellow countrymen. Most of the songs agreed that these soldiers were just as brave as their white companions, especially in battle, but all too often they claim that these men are the exception to the rule.

Return to the homepage here.

- Robert L. Douglas, “Myth or Truth: A White and Black View of Slavery,” Journal of Black Studies vol. 19 (1989): 348. ↩

Patriotism

Before television and radio became the main forms of entertainment in America, music was the primary outlet that U.S. citizens had for entertainment. This means that the themes discussed in the music had a tremendous amount of impact on how U.S. citizens viewed certain topics. Patriotism is a subject that can be easily manipulated. It is rare when a war fought by the United States is viewed with criticism, and all too often any dissent is silenced or ignored. Abraham Lincoln, commonly viewed as our staunchest supporter of liberty, suspended the right of Habeas Corpus on several journalists whom he felt did not support the American Civil War. In this light, the music of WWI and the Spanish American War provides an intriguing case study on how music can be used for propaganda purposes to support or, in rare situations, criticize war.

Minnie Lee Jeffords composed this song in 1917, the year the United States went to war in Europe. Typical of songs of the time, this is extremely supportive of the war and President Wilon’s decision to become involved. The lyrics claim that, “When foreign nations threaten to destroy our land…We are with you Mr. Wilson, it is up to you.”

This form of patriotism is dangerously close to jingoism: aggressive foreign policy fueled by extreme patriotism. The United States was not threatened by the Germans in WWI like the songs claims, but songs like these spurred on the populace to fight.

One facet of patriotism is distaste for foreign countries. The Spanish American War, perhaps best known for the advent of “yellow journalism,” yielded many fascinating songs. This song, If They’d Only Fought with Razors in the War, was composed by Irving Jones in 1898. The most memorable lyric of the song is when the protagonist claims that, “If they’d only fought with razors in the war, I’d certainly spilled a lot of Spanish gore.” Musical composers had no qualms with describing vivid, brutal scenes if it involved the enemies of America.

Patriotism comes in many forms, and this song composed by John F. Carroll in 1922 takes a different approach to the more bombastic songs shown above. Soldiers are well-respected while fighting enemies foreign and abroad but after the fighting ends they can be forgotten and tossed aside. Soldier Bonus Blues discusses this issue, and the lyrics are just as poignant today as they were in 1922.

“We’ve got the blues, the soldiers’ bonus blues, for we don’t think they’ll ever pay. We would not shirk if we could get work. We would do the ‘heavy’ every day.”

Return to the homepage here.

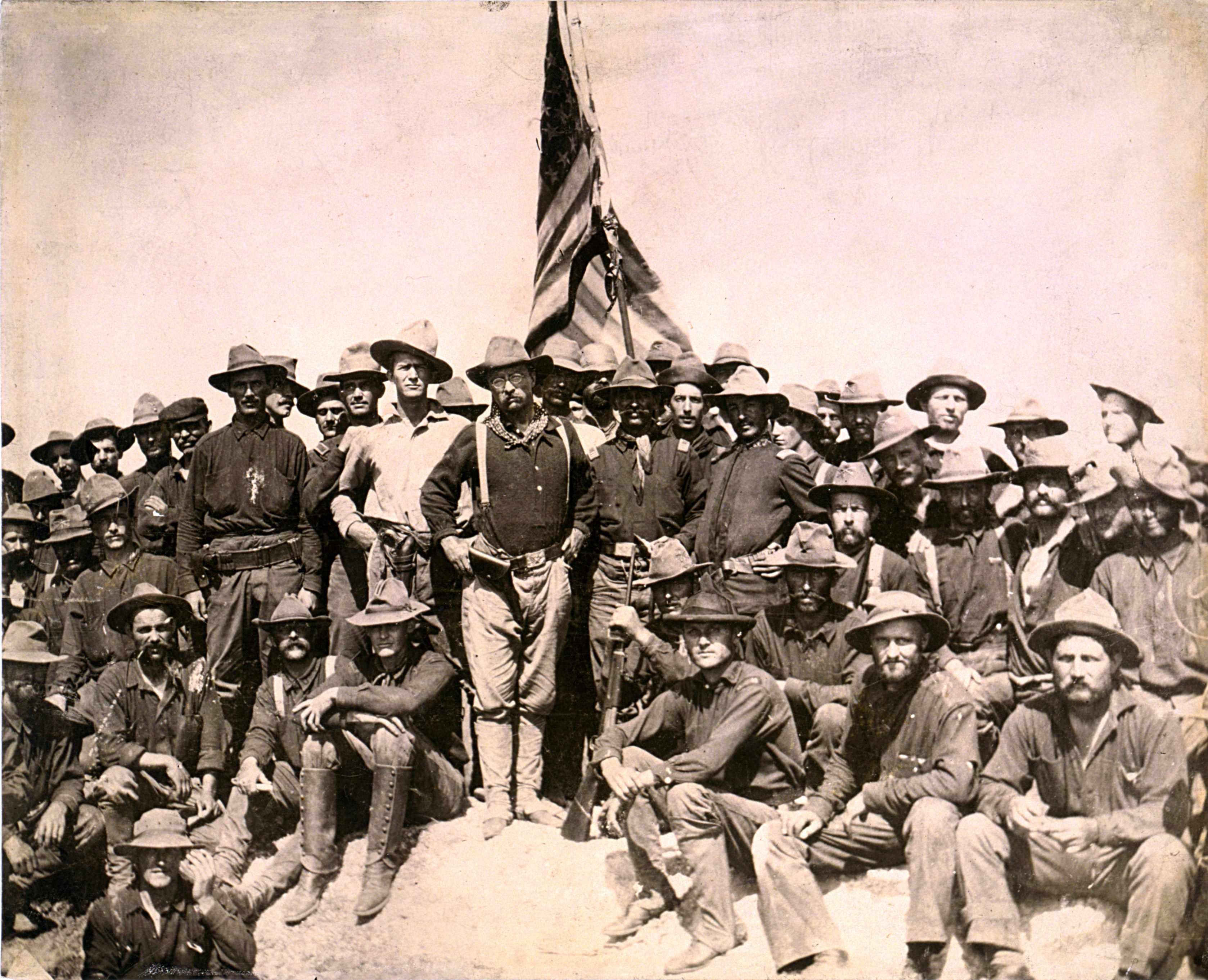

Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, 1898

Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, 1898