By: Sarah Pullin

Homecoming is one of the most precious and time-honored traditions at Baylor University. It started in 1909, and is still carried out in the present day over 100 years later. Baylor had the very first homecomings, which has now evolved into one of the largest. Homecoming is something that united both the current students, and invited the alumni to come back and reminisce on their college years. This weekend of events is something that even over the many years has changed little to none. It is something that is so loved and cherished by both alumni and current students and encouraged collaboration between the two. However precious this tradition, it was not consistent right after it first began. Baylor had to choose between tradition or patriotism.

The First Homecoming

This first homecoming was November 24 & 25, 1909. This was Thanksgiving weekend. Homecoming was a much-anticipated event. “It has been the dream for years of many of the former students and graduates of Baylor University to have some time a reunion of the large Baylor family” (Guittard, Pool, & Ragland). The “purpose of Home-coming was to give and opportunity for the joyful meeting of former student friends, an occasion when old classmates could again feel the warm hand-clasp of their fellows, recall old memories and associations, and catch the Baylor spirit again” (Hargrove, 1909). Professors F.G. Guittard, W.H. Pool, and George Ragland, who composed the general committee of arrangement, wanted to make sure that the alumni knew that they were not inviting them back for fundraising. “The purpose of the home-coming is to be purely social and fraternal” (Guittard, Pool, & Ragland). Baylor launched a massive outreach to their alumni publicizing this event. They sent out personal invitations written by students, which included signatures of several faculty members (As shown in the picture).

Homecoming also presented opportunities for different societies to have reunions. Excitement for this event reached the city of Waco, the state, and beyond. “Baylor’s campus was never a livelier scene than Wednesday and Thursday of Home-Coming. Hundreds of old and new students were meeting, renewing acquaintances, re-forming “ties” and sharing in the old-day college spirit and geniality (Minatra, 1909, p.4). Not only did Baylor bloom with anticipation and enthusiasm, but so did the city of Waco. “Not in many years was the city so generally decorated in honor of any occasion” (The Round Up of 1910, p. 154). By the time the weekend of homecoming finally came, spirit was at an all-time high. Alumni had come in from all over; “all parts of the State were represented by Baylor’s loyal sons and daughters” (The Round Up of 1910, p. 154). Some even came in as early as a week before. “The home-coming was probably the greatest affair of its kind ever pulled of in the state of Texas. This is true from every standpoint and in every phase of University life” (Minatra, 1909, p.4). Homecoming was not only an exciting event for the alumni, but it also unified the campus producing an event to be extremely proud of. “All hearts throbbed in unison of every glimpse of Green and Gold, and were bound by golden cord of love for our ‘Alma Mater dear’” (Minatra, 1909, p.4).

Program

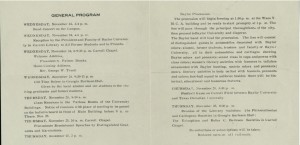

The weekend began on Wednesday November 24, at 3 p.m. with a band concert and lead immediately into a reception by the president and faculty. Following this was prominent ex-students speaking in Carroll Chapel. After the students spoke President S. Palmer Brooks gave a welcome address, and Rev. George W. Truett gave a Homecoming address. Extending late into the night was an “old time soirée” in Georgia Burleson Hall. “Given by the local alumni and old student to the visiting graduates and students” (Minatra, 1909, p. 2). Events began again at 9 a.m. Thursday morning with class reunions. After reunions, they allowed time for ex-students to give reminisce all together back in Carroll Chapel. At 2 p.m. was the Baylor Procession which went all the through the city and then through the campus. There were over 130 entries in the parade; about half of these were in automobiles and carriages. The rest were student organizations that walked on foot. Not only were some of the cars decorated, but local residences and business joined in the Baylor spirit as well. The Baylor Band led the parade, followed by alumni, students, trustees, faculty, staff and literary societies. The senior class marched in their cap and gown, and the football team was in their uniforms. The football team had to head over to the field quickly, because the game against TCU was only a half of an hour later. After the game was the final event of the weekend. This was the literary societies reunions in Georgia Burleson Hall (Odie, 1909, p.4). Below is a picture of the Homecoming program from 1910.

The Football Game

TCU was Baylor’s biggest rival. Because of this they thought it would be an extra incentive for alumni to come back to Waco. “Yet when it comes right down to the students themselves, there is no game like the Thanksgiving game; no contest appeals to them so much as does this last game of the season when amidst the smell of turkey and cranberry sauce” (Minatra, 1909, p.1). Baylor was correct in assuming that it would draw a large crowd. The crowd was nearly 5,000 people. This game became a tradition. It was usually very exciting because neither team was a clear underdog. It varied from year to year who was this winner of the rivalry. Baylor actually won their first homecoming game against TCU 6-3. “Hardly ever was there such rejoicing on Baylor Campus. Even certain of the visitors, who were inclined to think that football is a doubtful sport for college youth, caught the spirit and helped to swell the shout of victory”(The Round-Up of 1910, p. 154).

When Baylor played TCU in 1915, they won with a score of 51-0 “displaying a brand of football that would make the old Homecomers glance back into the past and compare the present eleven with the famous historic ones” (Walker, 1915, p.1). It was said that everyone on the team played like a champion, giving the whole team credit for the victory instead of one particular player. Baylor had gone without a mascot until 1914, when President Brooks let the students help to choose the mascot. For the second homecoming game fans actually say that “The Bears” won.

The Parade

The Round-Up of 1910 described the homecoming parade this way:

“One of the most interesting an even remarkable events of Homecoming was the procession…At 2 p.m. the procession started west on Washington Street, then proceeded on Eight to Austin Street, and traversed the principal thoroughfares of the city. It was a sight long to be remembered. The line extended a distance of twenty-five blocks, and all automobiles, carriage, buggied, and other vehicles were tastefully decorated with green and gold bunting and pennants; some automobiles were even profusely ornamented with yellow chrysanthemums; while the students on foot were adorned to suit individual tastes” (p.160).

When homecoming was brought back in 1915, the parade was referred to as a pageant. The third parade wasn’t until 1924, after World War I. It didn’t become an annual part of homecoming until 1945. Every class, society, and association participated in the pageant. The Baylor Band was usually the group leading the parade through Waco. “More time was spent on the Home-Coming Pageant than any other single part of the Home-Coming entertainment” (Walker, 1915, p.1). When floats first appeared in the parade, they were regulated by the Baylor Chamber of Commerce. One of the floats that stood out portrayed a freshman entering a main hall and coming out a dignified senior. This started the trend of themed floats that has continued even into the present day. However, it was not until the 1950’s that the floats started showing the homecoming opponents.

The Bonfire

There are aspects of homecoming that have remained almost exactly the same, and there are some elements that have evolved over time. The bonfire has been one of homecoming’s longest traditions that has not changed. The first bonfire was held in 1909 the night before the parade and game, which is the same as present day. However, in the beginning there were many bonfires around campus that the freshmen had to guard. This aspect had changed quite a bit over the years. At first TCU was the enemy who they were guarding the flame from. Tradition then involved stopping every car that drover through campus. The rule was that the person driving the car did not kiss their date, their date had to kiss everyone who was guarding the flame. This tradition did not last. The tradition then became for the freshmen to guard the flame from the upperclassmen. However, Baylor had to stop this tradition all together. The bonfire is still a tradition that has stood the test of time. However, now there is much more build up and show that go into lighting the bonfire.

A Time Between

After the first homecoming in 1909, there were six years that went by without a homecoming on Baylor’s campus. There is no clear explanation why it did not continue. However in 1911, Samuel Palmer Brooks gave a speech to the Third National Peace Congress in Baltimore. It was clear from his speech that there was unrest around the globe. He addressed how a university should respond by saying, “The school room is no longer a place for timid souls who fear to smack the images and traditions. Teachers may well learn to teach what ought to be, as well as what has been. Service to country is not opposition to others” (Brooks, 1911, May 5). Although America would not enter the war until 1917, many countries had already declared war on each other at that point. Brooks was very vocal about his feelings towards war and the proper reaction to it. “In theory all men prefer peace to war; in practice most men do. All good men are willing to pay the price of peace. All men do not agree as to the best means to its attainment” (Brooks, 1913). One of the many things that had to compromise during this time was homecoming.

The Next Homecomings

After the first homecoming in 1909, the next homecoming was not until 1915. When homecoming resumed in 1915 all classes since 1870 were represented. It was said that homecoming was to celebrate Baylor’s 70th anniversary. Homecoming’s planning was different this year. It was taken over by the alumni association this year. It seemed as though both the alumni and the student both missed homecoming while it was gone. A very conservative estimate of the expected attendance is placed at five thousands. “Letters, asking for further information and voicing the heartiest approval are coming from all parts of the United States” (Walker, 1915, p.1) The Round-Up added a special homecoming section to appeal to the alumni. Alumni also brought back the tradition of the TCU game over Thanksgiving. Another aspect they knew would appeal is having reunions with organizations and hearing some of the prominent Baylor alumni speak. “The eagerness is not confined to the Alumni. The present student body waits impatiently to extend Baylor’s hospitality to those who knew it first” (Walker, 1915, p.1). According to the Baylor Lariat published on January 28, 1915:

“The lovers of football will be assured of a fast and snappy game on this date, for the Purple and White tribe always in the running for the championship of the South. Coach Mosley last year welded together a winning combination and next year, if all the old men return, the Green and Gold team will stack up strong in the T.I.A.A. Everything being equal, the home-coming alumni will be greeted by a regular 1910 team in strength and ability.” (Roy, p.1).

Another Time Between

Baylor’s campus changed in many ways after America entered the war. Baylor participated in work drives and military training. “Chapel will take on a new appearance with four or five hundred men to khaki and the campus will be alive with soldiers all our own. Baylor tried to help out with the burden of the war in any way that they could. “’This war’ declared Mr. Thompson, ‘is no longer a war. It is a crusade for it is upholding the holy cause of liberty, justice, and democracy. The allies are fighting for conscience. They have morale’” (Youngblood, 1918, p.1) Baylor students had a shift of mindset. They say patriotism to their country as a duty. A lot of young men chose this duty over going to or finishing college. “All young men anxious to get to be officers as soon as they are eligible for war service should enter college and get the preliminary steps and then they will enter training camps vastly better equipped than the man who has not had this college military training” (Armstrong, 1918, p. 1).

After the second homecoming in 1915 another nine years passed before the third homecoming occurred. This elapsed time was due to America entering World War I in 1917. The third homecoming was not until 1924 when the alumni committee got back together and finalized plans for homecoming to be a permanent event. However, this homecoming was different. Instead of playing our traditional rival, TCU, Baylor changed their homecoming game to the game where Baylor played Texas A&M. This was mainly due to the fact that Texas A&M also held an important football game in Thanksgiving weekend. “Fifteen hundred old Baylor Exes will gather on Baylor campus Saturday, the day of the game, and arouse such a volume of enthusiasm among the Baylor students and the athletes, as well as themselves that the Farmer boys will go to the contest with a doubt” (The Lariat, 1924, p.4). They were going to come from miles away to support Baylor no matter when it was, where it was, or whom they were playing.

Conclusion

Baylor’s homecoming is claimed to be the oldest homecoming starting in 1909. It was somewhat sporadic when it first began. Students and Alumni both felt that homecoming was something they were willing to sacrifice when America entered the war. America citizens felt the weight of the war in their every day lives, which changed how their every day like looked. Homecoming eventually evolved into an annual event that has lasted over 100 years to current day. This weekend of events: parade, bonfire, and football games have all played a significant role in uniting past and current students. It unified students, alumni, and even the city of Waco. Homecoming was, and still is, one of Baylor’s most precious traditions that influenced students and student life

References:

Armstrong, A.J. (Ed.) (1918, August 22). Military Training. The Lariat. p.1

Baylor University Senior Class. (1910). The Round Up of 1910 (vol. 9). p. 154

Brooks, S.P. (1913). Newspapers and International Peace. A letter to the Galveston-Dallas News.

Brooks, S.P. (1911, May 5). The Schoolroom In The Peace Propoganda. Part of an Address Delivered at the Third National Peace Congress. Baltimore, MD

Guittard, F.G. , Pool, W.H. , Ragland, G. (Year Unknown). Baylor Home-Coming. Baylor University Home Coming.

Hargrove, H.L. (Ed.) (1910). The Home-Coming. Baylor University Bulletin, XIII (1), 1.

(1924, October 24). Homecoming Day to Be Made Annual Event: Work is Continued. The Lariat, p.4.

Minatra, O. (Ed.) (1909, November 26). Campus Scenes. The Lariat, p. 4

Minatra, O. (Ed.) (1909, October 30). The Homecoming Edition. The Lariat, p.1

Minatra, O. (Ed.) (1909, November 26). Old Folk Soirée. The Lariat, p. 2

Minatra, O. (Ed.) (1909, November 26). Opening Programs. The Lariat, p. 1

Roy, C.W. (1915, January 28). Strongest Football Schedule of Bear’s History Promised. The Lariat, p.1

Walker, H.W. (Ed.) (1915, December 2). Homecoming is Continual Gala Celebration of Many Features. The Lariat, p. 1

Walker, H.W. (Ed.) (1915, September 30). Member of Class of ’50 Will Be at Home-Coming. The Lariat, p. 1

Walker, H.W. (Ed.) (1915, November 18). Pageant to Be Feature Stunt of Homecoming. The Lariat, p. 1.

Youngblood, M. (Ed.) (1918, November 7). Baylor Takes Initial Step in United War Work Drive. The Lariat, p.1

I am writing an article on the origins of homecoming and the actual college website has nothing! thank you for writing this