by Sarah B Caldwell

During the 1930’s, institutions of higher education were faced with many obstacles, especially due to the historical context. Specifically, external factors such as the Great Depression had a major influence on these institutions and the decisions being made within them. In many ways, colleges and universities adapted to the culture and environment of the times.

In particular, Baylor University experienced dramatic fluctuation in enrollment numbers during the first years of the decade. Specifically, Baylor experienced a significant drop in enrollment within the first two years. However, by 1935, the institution had reached a record enrollment of 2,209 (author unknown, enrollment numbers, 1937). The sudden growth in numbers prompted discussions about expansion and led the university to consider ways it could improve the student experience. In particular, Baylor experienced the challenge of meeting the needs of its expanding population of students.

In regards to curriculum, the physical education department remained a stable part of the undergraduate requirements. As the student population grew, so did the need of support for this department. In order to provide each student with adequate resources, the physical education department was in need of development and university support. More specifically, the program at Baylor fell behind those at other institutions. For instance, when sending recommendations to Baylor president Pat Neff, department chair Lowell Douglas notes, “if we desire a program on par with other institutions I should say that such improvements are essential” (Letter to Pat Neff, February 2, 1937). In order for Baylor’s program to compare adequately to those at other institutions and to meet the needs of its many students, the department began a process of expansion.

Thus, the erection of the Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education Building was a direct result of this time of growth and development at Baylor. In addition, the development of the physical education program as a whole reflected the university’s care for student health and marked the beginning of the university’s efforts to promote overall wellness.

The Foundation

Baylor’s enrollment during the 1930’s was anything but steady, as the Great Depression caused a fall and rise in the number of students pursuing post-secondary education. Entering the 1930’s with an enrollment of 1,579, Baylor soon experienced the effects of the depression when enrollment dropped to 1,307 within two academic years (author unknown, enrollment numbers, 1937). Fortunately, the nation’s trials soon gave students a reason to attend higher education institutions and promoted enrollment, which caused Baylor’s enrollment to reach a record high (author unknown, enrollment numbers, 1937). The rising number of students choosing to attend Baylor caused faculty and staff to question the ways in which Baylor could uphold its mission and support a large number of students and their individual needs.

Even before plans for a new physical education building emerged, Baylor established a pattern of promoting physical health and wellness by requiring both male and female students to participate in two years of physical education courses, including a required course for freshmen students in Health Education. Trustee Earl B. Smyth noted such a longstanding commitment when he said, “through all of her illustrious history of nearly a century, Baylor University has stood for the spiritual, mental and physical development of her sons and daughters” (Dedicatory address, October 22, 1938).

The Creation of the Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education Building

As early as 1936, the Physical Education Department at Baylor had begun to submit requests for the growth and development of the department whether through the addition of faculty and programs for students. For instance, the rising number of female students, who were required to take physical education courses, validated Lucille Douglass’ request for additional faculty members to teach the classes (Letter to Pat Neff, October 16, 1936). Though seemingly large numbers at the time, the enrollment in the physical education department would only rise higher in the coming years, causing an even greater need for facilities and faculty support.

The creation of an athletic committee within the Board of Trustees provided an opportunity for trustees to weigh in on the presence of collegiate athletics and the promotion of such activities and programs on Baylor’s campus. Meanwhile, president Pat Neff’s idea to build a temporary gymnasium structure inspired several trustees to raise money for a permanent building (Blodgett, D., Blodgett, T., & Scott, 2007). Ultimately, the finances for the building were primarily provided through donations, and the decision to establish the new Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education facility was approved in early 1937 (Neff, Pat, letter to Trustees, August 28, 1937).

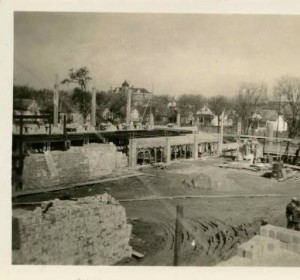

Plans for the building included descriptions as well as appropriate dimensions for gymnasiums, dressing rooms, and a swimming pool, among other features. The building plan also included office facilities for athletic coaches and physical education directors, which would promote student-faculty interaction within the department (Author unknown, RENA MARRS MCLEAN PHYSICAL EDUCATION BUILDING, April 26, 1937). Projected to open in June of 1938, the facility also featured equal arrangements for male and female students, as both genders had their own dressing rooms and private gymnasiums. “The building was the first permanent building Baylor itself had built since Brooks Hall in 1921” (Blodgett et al., 2007). That being said, the university took much pride in creating a facility that would later be acclaimed for its efficiency and “one of the most beautiful [swimming pools] in the Southwest” (Century, 1938).

The Celebrations

The construction and completion of the physical education building provided a time of celebration for the Baylor community. This is primarily seen within the cornerstone laying and dedication ceremonies, which took place in 1938. In addition to the structure itself, these ceremonies facilitated a time for the community to express its desire for student success and dedication to the wellness of its student body.

The laying of the cornerstone took place on Baylor’s Founder’s Day, February 1st, 1938. Many individuals were invited to attend the cornerstone laying ceremony. President Pat Neff even extended his own invitation to the greater Waco community (Neff, Pat, letter to readers of the Waco News-Tribune, undated). The cornerstone-laying program, steeped in religion and tradition, featured the university band and choir as well as an address from Dr. George W. Truett (author unknown, Program for Laying of Corner Stone of Baylor University Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education Building, February 1, 1938). Following, the audience gathered at the site of the new building in order to take part in the actual laying of the cornerstone “with the hope that the things deposited therein will be for the enlightenment of coming generations” (author unknown, Program for Laying of Corner Stone of Baylor University Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education Building, February 1, 1938).

After the facility had officially opened, the university gathered once again to celebrate with a dedication of the Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education Building on October 22, 1938. The dedication featured songs written for the McLean family in addition to other celebratory gestures (Grove, Roxy, song lyrics, October 22, 1938). The dedicatory address, given by Trustee Earl B. Smyth, featured remarks about the facility itself as well as his thoughts about the future of Baylor as an institution (Dedicatory address, October 22, 1938). In particular, Smyth notes, “not until the completion of this great building have we had here the facilities for providing for the proper physical development of the entire student body. Thus, this magnificent structure has ushered in a new day for Baylor” (Dedicatory address, October 22, 1938).

In simple terms, the building of this facility ensured appropriate consideration and support for the improvement of student health and wellness. Thus, it served as a turning point in the University’s ability to provide proper physical education and recreation services for students. It provided students with yet another means for improving their college experience, both inside and outside of the classroom. Woods even noted a correlation between the two, saying “the mind works better, thinks more clearly, and recalls more vividly when it is housed in a strong and healthy body” (Woods, L.W., Housing Healthy Minds in Healthy Bodies, undated). This simple remark illuminates the values of Baylor faculty and administrators and provides a starting point for promoting holistic education at Baylor.

The Development of the Physical Education Department

The presence of a stable curriculum and faculty support was vital for bringing this new facility to the Baylor community. The addition of the facility prompted the development of the curriculum, programs, and services offered by the department. The university-wide requirement for all students to complete courses in physical education provided a foundation for the advances made during this time. For example, the department expanded its degree plan to require 65 quarter hours (Bulletin, 1943). Coursework included multiple subject areas including kinesiology, health, athletic injury care, sports techniques, coaching, and theory. The 1939 Round-Up notes that the department reached “such a point in advancement that it now includes all of the major divisions usually recognized in this field” (Round Up, 1939).

The faculty also proved to be supportive of the development of the department. Many were vying for the installation of more faculty members in order to provide students with the best classroom experiences, while others were also engaged in the field’s latest research. For instance, Lowell Douglas was specifically interested in how health influences academic achievement (letter to Pat Neff, August 7, 1937). Given this and other expressions from faculty at the time, one can see how the development of the department as well as the university’s student body was valued.

In particular, faculty were interested in the ways that physical education and health influence the overall wellness of students. In a letter regarding the dedication of the new building, some faculty remarked, “we of the Faculty feel also a great concern over the mental and spiritual health of these same students” (dedication letter from faculty, February 1, 1938). In this letter, the faculty expressed the value of a holistic approach, taking into consideration all areas of student wellness. Ultimately, the faculty showed a desire to promote this type of holistic wellness at Baylor during this particular time period and in the future.

The Results

The new physical education building had positive effects for the department of physical education and students alike. In his letter to Pat Neff, trustee Hankamer notes, “the Physical Education Department, because of our new building, is rapidly becoming one of the major departments of Baylor” (Hankamer, Earl, letter to Pat Neff, May 29, 1939). Though students were required to take courses in physical education, the enrollment numbers within the Department of Physical Education still appeared larger than any year prior, given that the department had the second highest enrollment average of any campus department in 1939 with 739 men and 568 women enrolled, implying that student interest in the courses grew tremendously over a short time period (Bulletin, 1941).

Not only did the department reap benefits from this development, but also did the students. For example, the Women’s Athletic Association, an organization promoting women’s involvement in sports, “met with greater success during the past year than at any time since it was founded” (Round Up, 1939). In addition, it is noted that the new facility became responsible for “capacity crowds to watch intercollegiate competition” and “record-breaking student participation in the athletic program” (Round Up, 1939).

After the establishment of the new facility, the options for and variety of activities for students expanded tremendously. The number of students completing a Bachelor of Science in Physical Education also began to grow, and the degree attained a more stable presence within the university (Bulletin, 1943). “In addition to the program for students the department with its new facilities [developed] a large number of additional classes for both professional and business men and women” (Round Up, 1939).

These resulting advancements prove that the Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education Building served as a tremendous benefit for Baylor and her students. With the support of the university community, the installation of this new facility and the resulting development of the physical education program structure addressed student needs and promoted the holistic development of the student population at Baylor. These advancements are some of the many ways Baylor took action to improve the student experience and curriculum at the time. As Woods notes, “it is not enough to have worthy thoughts and attractive personalities. The thought and personality must be put into action. ‘Be ye doers of the word and not hearers only.’” (Woods, Housing Healthy Minds in Healthy Bodies, undated).

References

Author unknown. (1937 April 26). NUMBER STUDENTS ENROLLED IN BAYLOR UNIVERSITY IN THE LAST TEN YEARS. [Enrollment numbers]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 104, Folder 1). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Author unknown. (1938 February 1). [dedication letter from faculty]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 110, Folder 15). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Author unknown. (1938 February 1). Program for Laying Corner Stone of Baylor University Rena Marrs McLean Physical Education Building. [cornerstone laying program]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 110, Folder 11). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Author unknown. (undated). RENA MARRS MCLEAN PHYSICAL EDUCATION BUILDING. Pat Neff Collection (Box, Folder). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Baylor University. (1941). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor University. (1943). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor University. (1938). Baylor Century. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Blodgett, D., Blodgett, T., & Scott, D. L. (2007). The land, the law, and the lord: The life of Pat Neff. Austin: Home Place Publishers.

Douglas, Lowell N. (1937 February 2). [Letter to Pat Neff]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 151, Folder 4). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Douglas, Lowell N. (1937 August 7). [Letter to Pat Neff]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 151, Folder 4). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Douglass, Lucille. (1936 October 16). [Letter to Pat Neff]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 151, Folder 5). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Grove, Roxy. (1938 October 22). [song lyrics] Pat Neff Collection (Box 110, Folder 15). Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Hankamer, Earl C. (1939 May 29). [Letter to Pat Neff]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 139, Folder 13). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, Pat. (1937 April 28). [Letter to Board of Trustees]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 136, Folder 8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, Pat. (undated). [Letter to readers of the Waco News-Tribune]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 110, Folder 11). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Smyth, Earl B. (1938 October 22). [Dedicatory address]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 110, Folder 15). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

The Round-Up, (1938-1939). Waco, Texas: Baylor University.

Woods, L. W. (undated). Housing Healthy Minds in Healthy Bodies. [speech]. Pat Neff Collection (Box 110, Folder 16). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.