THE VISION OF A LITERATE WORLD: THE LOCAL, NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL IMPACT OF THE BAYLOR LITERACY CENTER

By Kevin Singer, PhD Student in Higher Education Studies and Leadership

Every night the lights burn, and illiterates become new literates. It has been exhilarating. But then literistics always is. We have seen the vision of a literate world…

Richard W. Cortright, Director of the Baylor Literacy Center, 1957-1961

On May 25, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave the commencement address at Baylor University. He emphasized the need for educational advancement in America. The 1950 US census showed that 10,000,000 Americans were functionally illiterate, having less than five years of formal education. Eisenhower anticipated that if the great universities throughout America devoted themselves to advancing education, “the prospects for a peaceful and prosperous world would be mightily enhanced” (Waco News-Tribune, 1957 18 October, p. 2-B). Eisenhower worried that the militant, aggressive Communistic doctrine beginning to dominate millions was an imminent threat that only educated people devoted to freedom could counteract. Following Eisenhower’s visit, a conference of educators, Baylor administrators and ministers met to discuss the implementation of his proposals. The conference recommended that a literacy program be established at Baylor to equip its students to teach others how to read, and the Baylor Literacy Center soon opened its doors in September of 1957. For the next eleven years, the Baylor literacy center would provide thousands of Baylor students and everyday citizens across McLennan County, Texas with literacy training. These teachers then taught thousands of people across McLennan County how to read. The early success of the Center prompted the establishment of numerous literacy initiatives in Texas and across the United States.

For the Baylor Literacy Center, however, literacy was a means to an end. Their strategy was what Roger M. Francis, a graduate student working for the Center in 1961, termed “Literacy Evangelism” (Baptist Standard, 1961 5 April, p. 6). If people were taught to read, they could read the Bible. If they could read the Bible, they could come to know Jesus. In coming to know Jesus, they might accept Jesus as the Lord and Savior of their lives and share Him with others. Given the staggering number of illiterates residing in McLennan County, across the United States and throughout the world, literacy evangelism had the potential to become a global evangelistic movement, and the Baylor Literacy Center hoped to be the center of this movement. For the next eleven years, the Center worked relentlessly to make this so, and their efforts were met with remarkable success. In this paper, the early history of the Baylor Literacy Center will be detailed with a distinct emphasis on their rationale, vision and strategy for literacy evangelism. The various aims they hoped to accomplish through literacy evangelism will also be explored, including the impact they hoped to make on international students during their time at Baylor. In all of this, I will demonstrate that the Baylor Literacy Center became far more than a noble effort to implement the commencement recommendations of a President; it became the center of a regional, national and international movement that sought to better the world and perhaps even change the course of its history. However, despite its accelerated success and wide-reaching impact, the Center only operated for decade. Thus, concluding comments will also be offered regarding the challenges that contributed to the Center’s closing in 1968.

Pre-Cursors: Frank Laubach, Communism, and the Call for Technical Missionaries

The Baylor Literacy Center’s secret weapon was its easy, replicable method for teaching people how to read. “Each One Teach One” was conceived by Frank C. Laubach, a missionary to the Philippines whose literacy tours to over 90 countries around the world resulted in nicknames like “Mr. Literacy” or “The Apostle to the Illiterates.” The boast of Laubach’s method was that it could quickly be paid forward; in just half an hour, someone could learn a lesson and then immediately teach that same lesson to someone else. Laubach’s method also emphasized the importance of the teacher-student relationship in literacy training. Both the act of admitting that one could not read and the process of learning how to read could be embarrassing, and would often deter people from starting the process altogether. However, if a trusting and confidential one-on-one relationship was established between the student and their teacher, there was a much greater chance of success. Journals from the Center’s teachers detail the impressive lengths they would go to in order to meet the unique needs of each student and build a relationship of trust. The students responded positively in kind; The Center’s Literary News in January 1961 documented the experience of Mrs. Rosa Vera, an immigrant who came to Texas from Mexico:

To begin with, I came to the U.S. less than three years ago, and if any of you have been in a completely different country without knowing the particular language of that country, I am sure you must know how I felt when I just came here. Then after being here for about six months…I met this very good friend who was my teacher: Mrs. Louise Whitehead, a lovely lady whom I am sure many of you know. I was so lucky that she was my teacher because she had so much patience and enthusiasm in teaching me that in a few months I learned to speak and understand English, which made my life much happier here. So, now I am teaching somebody else to read English and I only hope that, with God’s help, I can do for other people what Mrs. Louise Whitehead did for me. Since I’ll never thank her enough, I can always say, “God Bless Her.”

Laubach originally developed his method to build a stronger connection with the Moros, an Islamic tribe who lived on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. He learned to read in their language (Marahaw), and hoped that by using his method they might also learn to read as well. To jumpstart the process, he started producing a local newspaper in February 1930 and included tales of the tribe’s ancestors, current events going on in Mecca and the prices of local foodstuffs. Additionally, Laubach helped one of the Moros men to successfully complete the Hajj, the sacred pilgrimage made by Muslims to Mecca once in their lifetime. Because he was one of only a few Moros to accomplish this feat, he would come to be seen as a very important person in the tribe. From then on, he was called “Hadji.” The people of Mindanao developed a great love for Laubach, and the mere mention of his name could be a passport to safety among the less friendly Moros. Future missionaries to Mindanao noted that the Moros “changed from a hostile, distrusting, unlawful people to friendly, cooperative citizens” due to Laubach’s efforts (The Christian Science Monitor, 1956 14 November).

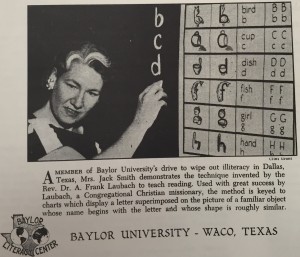

The “Each One Teach One” method begins with letters of the alphabet superimposed on the picture of a familiar object.

While on subsequent missions throughout Asia, Laubach began to notice two trends. First, he noticed that Communism was beginning to take hold across the continent. In a marketing brochure entitled “The Bible and Literacy” published in 1946, Laubach details the remarkable rise of literacy rates in Soviet Russia that began in the early 1930’s. From 1932-1944, 100 million people in Russia were taught to read, lifting the literacy rate from 13 to 90 percent. Russia then began printing more books, magazines and newspapers than any other country, and the rising literacy rate ensured that the Russian people could read them. Laubach attributed the impressive solidarity between the Russian government and its people to the rising literacy rates: “They read and believe Soviet teaching” (“The Bible and Literacy,” p. 2). This two-punch strategy of literacy and pro-Soviet reading was a force to be reckoned with, and it was spreading at an astonishing pace. Downtrodden people were particularly susceptible; they desired special skills in order that they might begin to help themselves. Whereas they considered the mere handouts of Western nations to be insulting and superficial, they considered the offer of literacy by the Communists to be practical and productive toward their cause.

Laubach began to recognize the urgency for a literacy movement to arise out the Christian West to counteract that of the Communists. Communism’s oppressive ideology and systematic effort to eliminate religion were legitimate threats to the very existence of Christianity in Asia. Laubach observed that as the literacy rate rose to 80% in Communist China, for example, “Christianity was practically crushed out” (The Daily Lariat, 1960 29 March). To incite buy-in, he sought to redefine the ideal missionary as a “technical missionary.” A technical missionary is one who not only shares the Gospel, but hands off technical skills along with the ability to read. He imagined that the thousands of young people graduating from American colleges every year would be ideal candidates, given their diverse skills from engineering to agriculture. To join in the mission, students simply needed to add the “Each One Teach One” method to their repertoire. In a speech given to supporters in Chautauqua, New York in 1958, Laubach exclaimed, “We have all the money we need, and all the technical skill we need. Thousands of young college graduates are chafing for the chance to go” (The Christian Answer to the Communist Threat, 1958). College graduates, after all, were looking for meaningful work and were eager to see the world. They also desired to be part of something revolutionary, something far bigger than themselves. Laubach hoped that American universities, especially those with Christian roots and commitments like Baylor, would buy into his vision and begin training students for the task of lifting a billion illiterates across the world out of illiteracy and poverty.

Laubach’s renown and calls for action quickly caught the attention of Baylor University leadership, and his influence at Baylor would have a sustained impact throughout the 1950’s and early 60s. Baylor President Dr. W. R. White voiced agreement with Laubach’s view that it is higher education that should provide the leadership for literacy. He commended the vision of those who were implementing university curriculum so that adult education specialists could obtain this kind of effective training (Oversea Education, Volume XXXIII: No. 2 – 1961 July). The Vice President of Baylor in 1961, Abner V. McCall, is quoted in the Center’s April 1961 issue of Literary News speaking similarly to Laubach regarding the worldwide political implications of literacy training: “In the struggle with Communist Russia and China for the new countries of Africa, Asia, and the rest of the world, we can win in the long run only if the citizens of these countries can read and thereby govern themselves to freedom.” When the “Each One Teach One” idea first occurred to Paul Geren, Executive Vice President of Baylor, it had “staggering grandeur” (Newsweek, 1958 7 July). Geren saw in Laubach’s method the capacity to fulfill the old Baptist dream of teaching everyone in the world to read well enough to understand the Bible. When Abner McCall was promoted to President of Baylor in 1961, his support for the Laubach-inspired literacy initiative did not waiver. Despite a complete reorganization of the Literacy Center in 1963, the Center’s new president J.B. Adair reported receiving “the approval and whole-hearted support from President McCall to propose that we conduct a state-wide literacy workshop on our campus to prepare leaders and workers for a state-wide emphasis on the removal of illiteracy” (Adair, J.B., 1963 25 September, Letter to Dr. T.A. Patterson, Executive Strategist – Baptist General Convention).

Richard Cortright Founds the Baylor Literacy Center

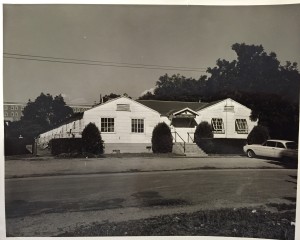

Despite the confidence of Baylor’s leadership, it would be difficult to imagine that anyone had as high a view of Laubach as Richard Cortright. Cortright, a graduate of the University of Michigan and the University of Indiana, traveled on a world literacy tour through 20 countries with Laubach. Along with applauding his pioneer international leadership in literacy, he called Laubach “one of the great religious leaders of our time” (Baylor Literacy Center Studies Number 7 – Writings By and About Dr. Frank C. Laubach, p. 2) After the tour concluded, Cortright was hired by Baylor in 1957 under the auspices of the department of foreign service studies. He was present when the conference on Eisenhower’s recommendations voted to start a literacy program, and on account of his experience with Laubach the conference promptly appointed him to be the program’s first president. They allocated a space for the new Center at 1318 South 9th street in Waco, a white-frame pre-fab that served as a storage room for 26 old refrigerators. Despite the humble character of the space, Cortright was enthusiastic and eager to get started. He resolved that the space would be “the sire for the first university literacy center. And it was” (Literary News, 1961 May). Cortright’s affections for Laubach inspired a relentless entrepreneurial spirit.

The Baylor Literacy Center at 1318 South 9th street in Waco.

The Baylor Literacy Center at 1318 South 9th street in Waco.

Dr. Richard Cortright at the front of the Center.

Cortright (right) and Laubach.

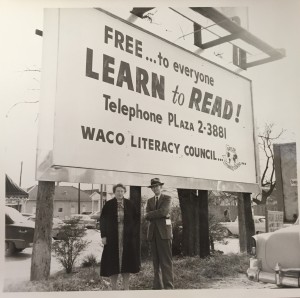

Cortright soon accepted his first students and promptly began training them to use the “Each One Teach One” method. He also began building partnerships with local churches, civic groups, businesses, schools and the Waco Farm Bureau. Baylor’s own McLennan County had 15,000 functionally illiterate individuals among its 73,950 residents according to the Waco Census, so Cortright decided that they would be the Center’s first priority. He distributed marketing pamphlets entitled “You Can Read This, But 10,000-15,000 Waco Area Citizens Cannot” and “Many of Your Neighbors Cannot Read” (1958 August). He also rented fifteen Waco billboards to advertise free reading classes. The first people to accept the offer were predominantly middle-aged and blue-collar, and their participation would remain consistent throughout the life of the Center. The popularity of the Center among middle-aged people confirmed that those who grew up during the Great Depression tended to be less educated due to the struggles and insecurities of that time period (Houston Post, 1959 18 October). Many of the students that came from McLennan County were also Hispanic or Black. Minority and immigrant populations tended to have greater difficulty gaining access to adequate educational resources, and thus were at a greater risk for life-long illiteracy. Several Literacy Center publications cite the story of one 80-year old African American woman who simply wanted to read the Bible in its entirety before she died. She was the first of many students who would come to the Center in hopes that they might learn to read the Bible. Susan Smith, one of the staff members at the Center in 1961, cited that “Reading the Bible is the reason nine out of 10 of the people are giving me as their goal for learning to read” (Baptist Standard, 1961 5 April, p. 6).

One of fifteen Waco billboards to advertise free reading classes.

Members of the Center’s staff share a meal with Black McLennan County residents.

One of the pamphlets that the Center distributed throughout McLennan County.

The “Each One Teach One” method begins with letters of the alphabet superimposed on the picture of a familiar object, in addition to combining phonetic sounds with sight objects. The goal, however, was for students to advance to the Bible reading stage which was accompanied by Laubach’s reading aid The Story of Jesus. This booklet contained simple stories about Jesus adapted from the four Gospels and was littered with reoccurring words to improve the reader’s confidence. However, it was not anticipated or expected that evangelism would begin in the Bible reading stage. Even in the earlier stages of the process, Laubach’s method anticipated that student learners would ask their teachers what compels them to be so helpful and generous with their time. Roger M. Francis, a graduate student who worked at the Center, recalled the way these interactions would typically take place.

While working with his friend through these early lessons, opportunities come to the Christian teacher to explain his faith. Such questions as these from new reasons open the way: “How do you get paid for this?” “Why are you teaching me?” The answer to the first question is, “I do not want money for pay. To be able to teach you makes me happy”…The second question is answered with, “I have a Friend who spent His life helping other people. He taught me the joy of helping people. I like to help you because Jesus taught me to love you. I want you to know Jesus like I do. You will soon be able to read about Jesus for yourself. See! Here is The Story of Jesus. When you have read these booklets then you will be able to read your Bible” (Baptist Standard, 1961 5 April, p. 6).

Francis perceived that the early stages of “Each One Teach One” presented opportunities for expressing faith and service in a natural, personal way. Nevertheless, it was more common for students to begin inquiring about Jesus during the Bible reading phase. Executive Vice President of Baylor Paul Geren, in his proposal to the Baptist General Convention on July 24 1968, described the Center’s philosophy well: “If a Bible is placed in the hands of a new reader by the Christian teacher who taught him to read, he will be more receptive its message.” This philosophy engendered successful results. Francis writes:

The readers are inspired by Jesus and challenged by His teachings! Jesus’ love and compassion draws them. They may tell their teacher: “I want to follow Jesus.” Or they may ask, “How do you become like Jesus?” That is the God-given time for the teacher to tell his own Christian experiences and to sow the seeds of faith.

In addition to taking advantage of these opportunities, teachers were also instructed to invite and encourage new readers to attend Sunday school and church. It was not uncommon for an illiterate to avoid these functions because of their inability to read the church bulletin or the Bible. Now that they could, it was anticipated that their interest might be rekindled. Attending these functions was also recommended as a good first step toward reentering some of the societal circles that they previously lacked the confidence to participate in.

After The Story of Jesus was completed, the student could proceed to learning how to read the four Gospels in the King James or Revised Standard Versions. From there, they could proceed to reading the book of Acts, the Epistles, the book of Revelation, and the Old Testament. If the student still had not expressed a desire be saved, the teacher was to present the way of salvation by using Scripture verses that the new reader could read for themselves. If the teacher felt untrained in this area, they could ask a fellow Christian or a pastor to go with them for a visit with the new reader’s permission.

Though introducing new readers to Jesus was certainly a high priority, this could not happen if not for a steady stream of teachers buying into the vision of literacy evangelism and participating in the mission. Cortright made sure to take time each year to revisit the Biblical basis for literacy evangelism and the spiritual rationale of reading in general. In one of his most popular studies, “Sharing the Saviour by Teaching Those Who Cannot Read,” Cortright cites a variety of Scripture passages from both the Old and New Testaments that emphasize reading as an important and worthy skill in the eyes of God. By thinking on these passages, Cortright hoped that a prospective teacher would gain valuable insight into how important it is to develop a concern for sharing the Gospel with those who are unable to read. He begins the study by citing Revelation 1:1-3, which reads “Blessed is he that readeth…” He then proceeds to cite passages in the Old Testament such as Exodus 24:12, which emphasize how important reading was to the ancient Hebrews; the law of Moses was written down and served as the basis of their religious beliefs. Cortright explains that in the time of the Old Testament, only a few could read. It was a great achievement and an honor to be among the literate. In 1950’s America, however, society scorned the illiterate rather than taking compassion on them and helping them learn.

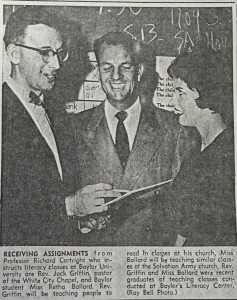

Cortright teaching the “Each One Teach One” method to a local Waco pastor (center) and a Baylor student (right).

Cortright hoped that this trend would be overcome by the love and compassion of Jesus. Turning to the New Testament, he cites passages such as Luke 4:16 that showcase Jesus reading, or passages like Matthew 12:4-8 in which Jesus tells his followers to read the Hebrew Scriptures and see their fulfillment in His words and deeds. Cortright also drew support from Church history, citing the persistent gratefulness of Christians throughout the centuries for the invention of the printing press. The printing press allowed them to make Bibles for all of the people in their own languages. This translation effort stemmed from the conviction that when a person reads the Bible for themselves, they come to know Jesus. Without Jesus’s own words readily at hand, one was vulnerable to temptation and even apostasy. Cortright tells the story of Christians in North Africa who could not read. When conquered by Muslim invaders and forced to submit to Islam, they could hardly continue in their Christian faith. He points to the fact that very few Christians still lived in North Africa at that time. In contrast, Cortright cites a group of Egyptian Christians who learned to read the Scriptures. They hid their Bibles in caves along the Nile to protect them from the invaders. Despite the persecution, they had their Bibles and constantly read them. Unlike the North Africans, their descendants remained Christians even at that time.

Cortright concluded his lesson by reinforcing the importance of teaching people how to read the Bible. When one reads the Bible, the Spirit of God dwells in them. They can learn what God wills and are then afforded the opportunity to follow Him. When one teaches an illiterate to read the Bible, it is as if they are sharing the knowledge of Jesus with them directly; and by sharing this knowledge of Jesus, one is also following Him. Cortright reminds his teachers that in reading the Bible, they should not reduce this exercise to merely sounding out some letters or spelling some words, but “reading to act” in the manner prescribed by the journey with Jesus through the Bible, a journey made possible by learning what is meant by “reading.” He concluded with a word of encouragement to take action: “We are now ready to set forth and teach others to read the Bible and thereby let them read Jesus’ own words by themselves” (p. 4).

Due to the evangelistic underpinnings of the “Each One Teach One” method, it was imperative that Cortright continued to resupply the Center with Christian teachers. His motto around Baylor was “Wherever there is a Baptist there is a potential teacher of illiterates” (Cortright, Richard, Many of Your Neighbors Cannot Read, 1958 August). His motto and his motivating presence seemed to catch on even long after he was gone. After the Center closed in 1968, the Baptist Student Union picked up the slack; they initiated a new literacy mission program that aimed to involve scores of Baylor students. The withdrawal of funding from the Baptist General Convention of Texas did not stop the BSU. They planned to run their program at no cost to the university (The Daily Lariat, 1968 25 September).

Global Scope

Increasing the McLennan County literacy rate was just one part of the overall vision for the Literacy Center. From its conception, the Center also intended to have a global impact. An article entitled “Literacy Center Meets Needs of World’s Urgent Problems” revealed that American students who enrolled at the Center’s literary studies program expected to be trained as literary specialists for work in the United States and abroad, in programs sponsored by governments, missions, foundations or other organizations (The Daily Lariat, 1958 25 November, p.3). Students from abroad who desired to return to their homeland to serve as officers in literary programs were also eligible and encouraged to enroll.

The Center’s global aspirations were informed first by Laubach’s growing international acclaim and his unwavering commitment to combat Communism in Asia. In a December 1959 article published in the Southern Baptist Educator entitled “Meeting 20th Century Needs,” Cortright writes, “The American and international students trained at the Baylor Literacy Center will be able to take active part in the vast ideological struggle between Christianity and communism by meeting the felt needs of the uncommitted millions who are still illiterate.” The Center’s global aspirations were also informed by the long-standing Baptist commitment to teach the Bible to all nations. In this way, Baptists regarded illiteracy as both a problem and an opportunity to reach the uttermost ends of the earth.

The Literacy Center adopted a multi-faceted strategy to address the concerns about communism and Baptist missionary ambitions. First, they would work diligently to identify and engage with international students at Baylor. In a letter dated November 18 1959, Cortright writes to W.R. Gooch, Baylor’s Administrative Vice President, that in order to better serve the international students on campus, they wrote individual letters to every one of them putting the Center’s facilities for teaching English as a foreign language at their disposal. They did this in hopes that some of these students might oblige to be trained at the Center and then return home upon graduation to teach and promote literacy in their home countries. In an article entitled “The War Against World Illiteracy,” Cortright explains,

What the foreign student learns in an American university will, hopefully, return with him to Asia, Africa or Latin America. His newly-acquired knowledge is bound to influence the national illiteracy, directly or indirectly, because whether he be an engineer, doctor or teacher, the foreign student will be in a position of leadership in his home land. He can, if he will, through his new status, help the village illiterate, a possibility that has not often been apparent to the foreign student while is working for his degree at an American university (Overseas, 1963 April, p. 1).

Cortright anticipated that a large number of international students would respond to the call. He cites that in his experience, international students are highly motivated to learn about literacy and do something about it, even if they are their interests lie in another discipline. His excitement about international students even led him to assert that “The foreign student of today is the leader of tomorrow” (p.3). They are the ones that bear the mantle of leadership for waging war against illiteracy. His suspicions were correct; by April 1963, the Center had completed some form of literacy training with 418 international students (Texas Literary Progress, September 1957-March 1961).

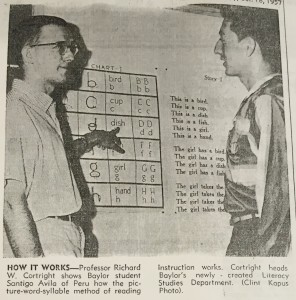

Cortright works with Baylor student Santigo Avila of Peru.

A second strategy that the Center enacted to achieve their global aims was to invite representatives from around the world to visit the Center and discuss the status of literacy in their countries. The purpose of these visits was also to explore how the Center might incite students from these countries to come to Baylor and be trained in literistics. A few months before Cortright stepped down as director of the Center, he recalls that during his tenure, a stream of people had visited from Malaya, Cambodia, Indonesia, Jordan, Hong Kong, Tanganyika and India (Literacy News, 1961 May). Sometimes, these visitors would stay for a longer duration to study and teach. One of the more noteworthy visitors was N. Bhadraiah, a well-known education theorist from India. Bhadraiah visited the center in hopes that Baylor might offer scholarships to students from India.

A third strategy was to offer foreign language courses to students who desired to do mission work. This included a course in Arabic, which Baylor asked an international student from Jordan to teach. Eventually, the Center adopted a fourth strategy for achieving their global aims that turned out to be the most effective. They created a system in which students could take the Center’s basic literistics course from their home countries and send in their completed assignments, culminating in an official certificate of completion. Hundreds of students from around the world took advantage of this opportunity. Using this multi-faceted strategy, the Baylor Literacy Center remained loyal and committed throughout its lifespan to making an impact on illiteracy beyond the United States.

Pro Ecclesia, Pro Texana

In addition to making an impact in McLennan County and around the world, some of the most impressive initiatives inspired by the Baylor Literacy Center came about in Texas and in churches across America. Richard Cortright was instrumental in founding the Texas Literary Council, the first of its kind in the United States. It was made up of university administrators, educators, and influential leaders from across Texas. Its annual conferences drew popular and innovative speakers from across the country, including Abner McCall when he was the President of Baylor. It also inspired the founding of literacy councils in Mississippi, Arkansas, New Mexico, Georgia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Tennessee, California and Colorado, in addition to the 35 literacy councils that would be established in Texas alone.

Another significant initiative inspired by the Literacy Center was a systematic effort to reach Latin Americans that had immigrated to Texas. Out of the 76 counties in Texas that had an illiteracy rate of 10% or more, a majority of them had a high percentage of Latin Americans who could not read. The Literacy Center partnered with Baptist churches and mission organizations across Texas to distribute Bibles and other reading materials to them. The Center also set out to equip Latin American pastors to start their own literacy centers and councils. Latin American countries possessed staging illiteracy statistics at the time. Haiti, for example, had at 90% illiteracy rate. The Center was compelled to take action, but did not need to go across the ocean to make an impact; Latin Americans had already settled in Texas.

Cortright was persistent in encouraging churches inside and outside of Texas to host or sponsor literacy workshops to train their members in literacy evangelism. He encouraged this route as the best in-road for Christians who were impressed by the Laubach method or were simply curious about it. He hoped that churches would begin to view literacy not as “something for foreign missions,” but a cutting edge method to be used by today’s awakened churchmen (Religious Education, 1961 January-February, p. 62). He envisioned that literacy workshops could be incorporated into on-going plans of adult religious education. He presented his case for literacy programs in a 1961 article entitled “Religious Education for 10,000,000 Americans.” He writes,

Literacy programs provide an opportunity for lay leadership to play a vital role in church life. There is no reason why the use of Literary Workshops could not be sponsored by any church in any community in America to carry on a proper educational responsibility. To this end, local groups of churches, whether they be synods or associations or dioceses or conferences, have rich new experiences in store for them as they watch the enlightened faces of New Readers reading their Bible for themselves. (p. 62)

Perhaps his most effective selling point, however, was the reality that many of functionally illiterate people did not belong to a church because they were too ashamed to attend due to their illiteracy. His message caught on quickly, such that churches across the nation from all major denominations were adopting literacy training as a major part of their evangelistic strategy. Cortright testified of Methodists working among the Spanish-speaking migrants in the West, Presbyterians sponsoring literacy workshops in the Central states, and Episcopalians opening literary programs in the Southwest. Some churches even built bridges across denominational boundaries to host workshops. One newspaper clipping tells of an orientation course in Austin that was sponsored by Colegio Biblico: First Methodist Church, La Trinidad Methodist Church, First Baptist Church, Mexican Baptist Church, Our Lady of Refuge Church and Church of the Redeemer (Unknown, 1958 16 October).

Undeniably, the Center was most effective in its efforts to mobilize the churches of the Southern Baptist Convention. This is due in large part to the intercessory work of Paul Geren. He wrote on behalf of the Literacy Center to the Baptist General Convention of Texas, in hopes that he might galvanize them to offer their full allegiance and support. In his address, he sought to provide assurance that the mission of the Center is cohesive with the mission of the Convention and with the mission of the Gospel:

The program is to be based at Baylor University but is not to be confined there. With one of its arms it will reach all across the state. With another it may reach to the uttermost ends of the earth. This is a sign of the attempt of Texas Baptists to be true to the spirit of the Gospel. It would hardly be in keeping with the Gospel to be concerned for illiterates 10,000 miles away and to have no compassion for the man next door who cannot read (Baptist Standard, 1957 14 September, p. 8).

He also appealed to one of the foundational principles of Baptist salvation doctrine, the responsibility of each believer to be their own priest. To be faithful to this responsibility, one needs to be able to read the Bible for themselves. Geren also quelled the Convention’s fear that literacy would be fighting fire with fire, seeing as the Communists were producing new literates and literature for them to read at a remarkable pace. He wrote, “We are not to refuse to teach literacy because Communists are turning out books” (Baptist Standard, 1957 14 September, p. 8). More importantly, Geren insisted, was the fact that “the peoples of Asia and Africa hunger and thirst for literacy and this may be a means to meet the blessed hunger for righteousness” (Baptist Standard, 1957 14 September, p. 8). If the Convention would only fixate their lens on the exciting possibilities literacy evangelism presented for Gospel growth, they would see its enormous potential to help them accomplish their mission.

Geren’s address was effective, as it helped to ensure that half of the Center’s funding would continue to be provided by the Baptist General Conference of Texas (BGCT) for years to come. It also inspired the Convention to undertake literacy programs in the Appalachian Mountains among some of the most undereducated people in the United States. The SBC’s Women’s Missionary Union (WMU) also joined the cause. One of the most staggering displays of support for literacy evangelism in America occurred when Mrs. B.W. Medlock, president of the Atlanta Baptist Woman’s Missionary Union, led the Union’s 20,000 members in sponsoring Georgia’s first Literacy Workshop. Her vision was that Atlanta’s 50,000 adult illiterates could be taught to read and write in five years using the Laubach method (Home Missions, If I Could Only Read, p. 21).

In addition to assisting with church literary programs in Texas and around the nation, the Center produced brochures, short films, slides, church bulletin blurbs, sermon ideas for pastors, and suggestions for incorporating literacy missions in Sunday School and other programs. A center staffer could also be made available for personal appearances if desired. All of this was performed in hopes that literacy training would become a coordinated nation-wide effort to reach those who were not only blind to the printed page, but blind to the great spiritual truths that God wanted them to know.

The Baylor Literacy Center logo, developed by Cortright.

The Literacy Worldview

In just four years between 1957-1961, the Baylor Literacy Center trained 1,956 Baylor students and Waco residents to be literacy teachers (2,200 by 1963). 1,345 adults were taught how to read in Waco, and 3,261 adults throughout Texas in all. 61 workshops were held in 41 Texas locations, in addition to the 23 workshops held in other states (Texas Literary Progress, September 1957-March 1961). Numerous international students were equipped to return home as literacy leaders, in addition to the hundreds of international students who participated in the Center’s basic literistics course from their home countries. Dozens of literacy councils were started in Texas and across the United States. Hundreds of churches from a variety of denominations began engaging their mission fields with Laubach’s method. Richard Cortright, however, came to believe that “Each One Teach One” was more than just a method; it was a “literacy world view” (Elementary English, 1963 March, p. 299).

This term effectively communicates the kind of impact the Baylor Literacy Center had throughout its pivotal early years. It was not just a noble effort to implement the commencement recommendations of a President; it became the center of a regional, national and international movement that sought to better the world and change the course of its history. Founded on the principles of political and religious freedom, the Literacy Center provided an alternative to Communism for the world’s most vulnerable. Founded on the love and compassion of Christ, the Literacy Center provided the theological resources for people to carry the burdens of their illiterate neighbors rather than looking down upon them. Founded on Einsenhower’s call for a revolution in American education, the Literacy Center widened its scope to reach the children of the Great Depression, Latin American immigrants, African Americans and Hispanics, the elderly, adherents of non-Christian religions, and churches from every major denomination. The Center did more than merely propagate a clever method for teaching people how to read; it introduced what Cortright called “the vision of a literate world” (Literary News, 1961 May). In a literate world, people would be free to help themselves in every way including spiritually. They could read the Bible for themselves and commune with Jesus Christ. They would no longer be slaves to exploitive practices, but priests who steward their own destinies. They would pay what they have been given forward for the common good of their regional, national and international neighbors.

This vision, though compelling, was short lived. Cortright admitted that despite the Center’s early success, they had not yet scratched the surface. Though 10,000 Wacoans could not read the newspaper, the Center struggled to solicit an attendance greater than 30 in their literistics class each semester. Cortright also admitted that although illiteracy was decreasing gradually through the Center’s efforts, it was not decreasing rapidly enough to demonstrate a formidable dent; every year, 60,000 new functional illiterates had to be accounted for. Perhaps the greatest challenge, however, was sustaining a charitable public attitude toward illiterate persons. For every person who felt compassion for someone who couldn’t read, there were two people who believed that illiterates were having an adverse effect on the nation’s economy, slowing technological progress and increasing safety hazards. Cortright explains, “Our industrial society is becoming increasingly inhospitable to the illiterate. As more businesses industrialize, and agricultural activities depend on the written word in their operation, the illiterate becomes less and less wanted” (Adult Leadership, 1959 June, p. 1).

A crippling blow was effectively dealt when Richard Cortright resigned from his position as President of the Literacy Center to work for Laubach’s literary foundation in Washington D.C. The Center struggled to maintain the energy and enthusiasm that Cortright invested throughout his tenure, and it subsequently became harder and harder to convince Baylor and BGCT leadership to continue funding the project. Finally, the Center closed its doors in September of 1968. Despite the university’s inability to continue financing the project, President McCall remained hopeful that some organization would step forward and attempt to sponsor the Center with a substantial sum of money, or at least the $10,000 or $15,000 that Baylor previously budgeted for it (The Daily Lariat, 1968 20 September, p. 1). By that time, however, the “literacy worldview” was beginning to lose its luster and the momentum that it engendered in its early years.

Conclusion

The relatively short life of the Baylor Literacy Center does not diminish the fact that the initial advancements made by the Center were swift and impressive. They provided the fuel to ensure the Center’s continued relevance and sustained impact throughout the next decade. What began as a lofty recommendation in a Presidential commencement speech came to fruition in exhilarating and unexpected ways, not just locally in McLennan Country but nationally and internationally. What resulted was the compelling vision of a literate world, and the accommodation of a “literacy worldview” by individuals, churches and mission organizations. Seldom does one expect a social or ecclesial movement of this caliber to come out of a Presidential commencement speech, and one that far exceeds the expectations of the President himself.

Works Cited

15,000 Adults Here Can’t Read Papers. (1958 January 23). [Clipping]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #1). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Adair, J.B. (1963 September 25). [Letter to Dr. T.A. Patterson]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #1, Folder #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Baylor Center to Lose Two Staff Members. (1961 August 11). The Daily Lariat, p. 1. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/15210/rec/7.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1957 September-1961 March). Texas Literacy Progress. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1958 July 7). “How to Make President.” Newsweek.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1960 March). Literacy News.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1960 September). Literacy News.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1961 April). Literacy News.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1961 January). Literacy News.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1961 May). Literacy News.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1961 October). Literacy News.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1963 May). Literacy News.

Baylor Literacy Center. (1968 July 24). A Proposal to the Baptist General Convention of Texas. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #1, Folder #1). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Baylor Literacy Center. (n.d.). “You Can Read This but 10,000-15,000 Waco Area Citizens Cannot” [Advertisement]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Baylor Literacy Center. (Reprinted from 1958 August Royal Service). “Many of Your Neighbors Cannot Read” [Pamphlet]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #6). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Belden, Tom. (1968 September 20). “Baylor Literacy Center Closes After 12 Years.” The Daily Lariat, p. 1. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/28956/rec/2.

Cline, William. (1967 November 22). “Literacy Center.” Baylor News Bureau, p. 1-3.

Collins, Emmet. (1959 October 18). “Illiteracy: A Texas Problem.” The Houston Post, p. 1-3.

Cortright, Mabel M. (1956 November 14). “Pilgrimage to Dansalan on Lake Lanao.” The Christian Science Monitor.

Cortright, Richard W. (n.d.). Writings By and About Dr. Frank C. Laubach. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #4). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Cortright, Richard W. (1957 November-December). “So Everybody Will Know.” The Baylor Line, p. 6-7.

Cortright, Richard W. (1959 December). “Meeting 20th Century Needs: The Baylor Literacy Center.” The Southern Baptist Educator, p. 12.

Cortright, Richard W. (1961 April 22). “The First University Literacy Center.” Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #3). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Cortright, Richard W. (1961 January-February). “Religious Education for 10,000,000 Americans.” Religious Education, p.61-62.

Cortright, Richard W. (1963 April). “War Against World Illiteracy.” Overseas.

Cortright, Richard W. (1963 March). “‘Each One Teach One’: The Right to Read.” Elementary English, p. 301-302.

Cortright, Richard W. (n.d.). “Sharing the Saviour by Teaching Those Who Cannot Read.” Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Cortright, Richard W. and Douglass L. Kelley. (1960 June). “‘I’m Tired of Looking at Blank Signs: The Story of the Texas Literacy Council.’” The Texas Outlook, p. 14-15.

Cortright, Richard. W. (1958 April 14). [Letter to Grover]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #1, Folder #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Cortright, Richard. W. (1959 November 18). [Letter to Dr. W.T. Gooch]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #1, Folder #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Dr. Cortright to Open Literacy School Tonight. (n.d.). [Clipping]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #3). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Durham, Jacqueline. (n.d.). “If I Could Only Read.” Home Missions, p.20-23. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #3). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Editorial. (1961 July). Oversea Education, Volume XXXIII; No. 2.

Francis, Roger M. (1961 April 5). “Literacy Evangelism.” Baptist Standard, 6-7.

Geren, Paul. (1957 September 14). “That More May Read.” Baptist Standard, p. 8.

Hoosier Native Heads Baylor’s New Department of Literacy Studies. (1957 October 18). The Waco News-Tribune, p. 2-B.

Johnson, D. Edwin. (n.d.). “Unusual Program at Good Street Church.” [Clipping]. Churches. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Johnson, Eve. (1958 November 25). “Literacy Center Meets Needs of World’s Urgent Problems.” The Daily Lariat, p. 3. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/18593/rec/1.

Laubach, Frank C. (1946). “The Bible and Literacy.” 130th Annual Meeting of the American Bible Society.

Laubach, Frank C. (1958). “The Christian Answer to the Communist Threat.” The Koinonia Magazine.

Learn to Read. (1959 February 5). [Clipping]. The Waco Times-Herald, pg. 8-A. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #5). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Lee, Dallas P. (1963 October 30). [Letter to J.B. Adair]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #1, Folder #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

“Literacy Class Asks For Helpers.” (1958 October 21). [Clipping]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #4). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Literacy Studies. (n.d.). [Clipping]. The Waco Times-Herald. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #4). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

McBeth, Mona. (1957 December 11). “Baylor Literacy Plan First in Southwest.” The Daily Lariat, p. 3. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/12933/rec/2.

Rotary Hears Chief of Literacy Council. (1958 December 12). [Clipping]. Baylor Literacy Center Collection (Box #11, Folder #7). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX.

Simple Challenge Results in 2,500 Learning to Read. (1963 December 12). The Waco Times-Herald, p. 2-B.

Taylor, Larry. (1968 September 25). “BSU to Sponsor Literacy Mission: Program for Waco Illiterates One Phase of BSU Activites.” The Daily Lariat, p. 1. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/29059/rec/4.

Waco Editor Offers Awareness. (1960 March 29). The Daily Lariat, p. 2. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/13916/rec/4.