By: Cara Allen

“Photo Courtesy of Baylor Texas Collection”

During the 1920s religious work dominated the student organization scene on Baylor’s campus. Every time the Baylor newspaper went to print it featured the religious section that reported on what was happening within the religious life of the campus. The yearbook was littered with religious undertones such as labeling the library as “the place we take our daily pilgrimage” (Round Up, 1922). The formation of the Baptist Student Union perpetuated the strengthening religious culture on Baylor’s campus. Many students’ long time desire for a Baptist-specific religious organization finally came into fruition at the beginning of the era. Though many perceived the creation of the Baptist Student Union as a success, the organization’s existence resulted in a dominating presence of the Baptist Student Union on campus. The religious programs previously represented on Baylor’s campus through the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Young Women’s Association were ended. The reaction against interdenominational groups that contributed to the creation of the Baptist Student Union also resulted in the neglect of students that were not affiliated with the Baptist tradition.

The Need for Christian Organizations on College Campuses

During the early 1900s the growth of state schools and their increased secularization provoked the need to start religious organizations on college campuses that did not have roots within the church. The Christian students attending these schools wished for a community of believers to unite with, and the vision for religious programs grew (Boone, 1953). Organizations, such as the Y.M.C.A., were concerned with creating interdenominational religious organizations on campuses (Boone 1953). Many Baptist students joined these initiatives and eventually went on to work for these programs. Though interdenominational organizations were popular across the nation on college campuses, a group of Baptist students at Baylor University sought to create a Baptist Student Program that would serve to oversee all religious functions on campus.

Baylor Students’ Desire for a Baptist Student Union

From 1904-1920 students at Baylor began to earnestly seek the opportunity to create a Baptist denominational religious program on campus, and both students and faculty began to pray that one would emerge (Boone, 1953). Students and faculty in support of the Baptist organization were concerned that “groups of strong students were influenced by the interdenominational student religious programs” (Boone, 1953, p. 4). Consequently, many men and women “were lost to our [Baptist] churches and our denomination because we [Baylor] did not have a strong Baptist student religious program” (Boone, 1953, p.4). The statement suggests that problem on Baylor’s campus emerged from the concern that the interdenominational programs at Baylor, such as the Y.M.C.A. and the Y.W.C.A., were leading students away from the Baptist tradition towards other denominations.

In 1904, Joseph Boone, along with five other students, began to pray daily that God would lead the campus in launching a Baptist Student Program (Boone, 1953). During this time, the Y.M.C.A. began an interdenominational program in Texas and asked if Baylor’s Joseph Boone would be secretary. Despite urges from President Samuel Palmer Brooks, Boone turned down the offer because of his commitment to the creation of a Baptist student program at Baylor (Boone, 1953). Boone and his friends, even more than Baylor’s president, wished for a Baptist student program. Boone’s rejection of the position with the Y.M.C.A. reveals his deep desire for a Baptist-specific organization. Select Baptist students wanted to see the will of God emerge through the Baptist tradition on Baylor’s campus, not through work with other denominations. Their primary concern was that Baylor began as a Baptist institution, and the Baptist denomination had sacrificed to keep the school open. Furthermore, concerned students wanted the religious organization to remain true to Baptist tenants and doctrine to create a sense of denominational loyalty in the lives of students (Clower, 1944). The desire was for the Baptist tradition at Baylor to remain central to the campus’ mission, and the students’ religious development. The rejection of the secretary position revealed Boone’s belief that Baylor should remain faithful to her Baptist roots.

The Formation of the Baptist Student Union

In 1919, the Baptist State Executive Board of Texas began gaining interest in and discussing the formation of a Baptist Student Program on Texas campuses. In the fall of 1919, the State Baptist General Convention created the Department of Student Work and placed former Baylor student Joseph Boone as the secretary. Part of his role was to create a program for student religious development. In 1920, Boone held a conference with representatives from Baylor University, Mary Hardin Baylor College, Southwestern Seminary, Decatur College, University of Texas, and A&M College to determine the role and name of the organization (Boone, 1953). The name “Baptist Student Union” was carefully chosen. Each word represents an aspect of the organization they wanted to highlight: Baptist heritage, student focused, and union, representing unity in beliefs, actions, and fellowship (Boone, 1953).

Although Boone had success in creating the organization, the Great War created problems with the name on campuses. The Y.M.C.A. and the Y.W.C.A. found their place on many college campuses as a result of their role in military camps. Many of the denominational colleges trained the men and women in the armed forces. As a result, many college leaders were not as quick to emphasize the title “Baptist Student Union” because of the denominational affiliation (Boone, 1953). At Baylor specifically, there were differences in opinion in establishing the B.S.U. on campus. In the end, a group of Baptist Students convinced President Brooks to allow the organization on campus, and Baylor quickly became the hub for the Baptist Student Union (Boone, 1953).

It did not take long for Baylor to find her leadership role as the B.S.U. headquarters, and the college created the first Baptist student organization on college campuses in October of 1921. Students at other institutions in Texas quickly reacted against the growing push for interdenominational organizations on campuses, and alongside the Baptist General Convention of Texas, created their own organization that trumped all other religious organization on Baylor’s campus for many decades to come.

Baptist Student Union’s Role

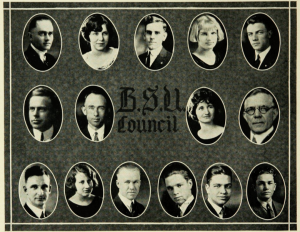

The Baptist Student Union became the home for all of the religious activities on Baylor’s campus. The B.S.U. was structured with a council of students representing each religious organization and a professor. These students reviewed all of the different religious activities and programs on campus. This structure kept the school from having too many different religious organizations, as well as provided oversight so that different

“Photo Courtesy of Baylor Texas Collection”

organizations did not have overlapping activities (Baylor Bulletin, 1928). Furthermore, the council studied the different religious needs on campus to ensure that the B.S.U. was adequately meeting specific student’s religious needs. They also coordinated and advertised all religious activities of the institution. This left little room for non-Baptist students to exercise their religious preferences on campus because all religious organizations were now affiliated with the Baptist tradition (Baylor Bulletin, 1928). Any member of an organization underneath the B.S.U. automatically became a member of the over-arching organization. Furthermore, the B.S.U. carried out mission work outside of Baylor and within the community of Waco (Baylor Bulletin, 1928). The B.S.U. also planned and held a yearly revival as well as weekly religious meetings.

Organizations Under the B.S.U.

The Baptist Student Union monopolized all religious organizations on campus. After the creation of the B.S.U., religious organizations that were already in existence were now under the authority of the B.S.U. and the Baptist General Convention. Students that were not Baptist but were a part of the religious organizations before the B.S.U. was created lost their place in the religious work on campus. Baptist students gained many opportunities to engage in co-curricular activities that coincided with their faith that the non-Baptist students did not reap the benefits of having. Underneath the B.S.U.’s umbrella was: a general weekly B.S.U meeting, the Preachers Association, the Volunteer Band, a Special Workers Band, the Baptist Young People’s Union, a College Women’s group through the Y.W.A., as well as Sunday School Classes at the First Baptist Church and Seventh and James (Round Up, 1922). The benefit of an all-encompassing religious organization that housed the different religious groups on campus was that “each group knows the problems and triumphs of the other” as well as “student talent and leadership is divided by all the organizations, and not monopolized by one or two” (Baylor Roundup, 1927, p. 120). The options for Baptist student participation remained extensive, but the options for non-Baptist students were limited to non-existent .

The Preacher’s Association, or what became known in the middle of the era as the Ministerial Alliance, consisted of ministerial students at Baylor. This is one of the oldest religious organizations on Baylor’s campus, because one of the reasons for Baylor’s founding was to train ministers (Baylor Roundup, 1927). Many of these students held preaching jobs at churches throughout their time at the university. Some were “stock” preachers that traveled to different churches that needed a speaker on Sundays, and some held permanent positions at churches. As one might expect, this organization comprised solely of men, and they selected a different president for each term (Baylor Roundup, 1923). The group reported back to the B.S.U. how many conversions occurred within their churches, number of sermons preached, and number of baptisms throughout the year. They also raised funds for the state denominational program that created the B.S.U. As a result, Baylor’s B.S.U. received some of this funding to help fund their organization (Round Up, 1927).

The Volunteer Band was one of the largest groups within the B.S.U. The group was broken up into smaller committees consisting of a membership committee, a social committee, and chief officers (Student Volunteer Band). Their local and foreign mission work consisted of extension work into the city such as jail and street ministries as well as ministry to the poor (Baylor Roundup 1924). They spent many Sunday afternoons working in the city and the county jails, a country farm, and on the streets of Waco (Student Volunteer Band, 1924). The students not only did local work, but they also worked to send students abroad (Student Volunteer Band).

The Young Woman’s Auxiliary was one of the primary ways that Baptist women were involved in religious organizations on campus, outside of the Volunteer Band and the B.Y.P.U. The group trained women how to show “consideration, gentleness, and Christian responsibility ‘for the other young woman’ for whom they come in contact” (Round Up, 1927, p.123). The women sought to require high standards of women in both the public sphere and the private sphere, and to encourage reading the Bible and spending time in Prayer. In 1927, over 135 girls participated in the organization and were split into six smaller groups (Round Up).

The Sunday School classes at Seventh and James and First Baptist Church met on a weekly basis. The classes were divided between males and females and had a close affiliation with the University. These two churches held the largest Sunday School classes for college-aged men and women in Waco (Baylor Roundup, 1924). Baylor students that attended other Sunday School classes at non-Baptist churches were not acknowledged on campus as organizations, nor were they represented in the yearbook.

The Baptist Young People’s Union (B.Y.P.U.) was an organization underneath the B.S.U., but the unions were held and supervised by Seventh and James Baptist Church as well as First Baptist Church. The B.Y.P.U. was formed during the late 1800’s when young Baptists wanted to join forces to organize themselves and utilize their gifts to serve the church (Conley, 1913). The B.Y.P.U.’s at Baylor emphasized Christian training and had a large number of participants (Round Up, 1927).

The Special Workers Band was a catch-all organization that fulfilled all of the religious work left in the community that the other religious organizations did not do. The members of the organization taught the B.Y.P.U. study courses and Sunday School classes, as well as any other religious-educational work that needed to be done within the churches in Waco. They not only worked in the more prominent churches in Waco, but they also sought to help churches that were small and struggling. They helped teach lessons and provide support for the churches in need (Baylor Roundup, 1927). Thus, The Baptist Student Union created an organization that would fill in the gaps that the other religious groups were not covering. This responsibility could have easily been given to the non-Baptist religious students, allowing them a place within the fabric of the religious community on campus. Instead, the B.S.U. continued to work alone rather than alongside other organizations, such as the Y.M.C.A.

Each year, the B.S.U. collaborated with Baylor University to hold a yearly revival. During this time, classes were canceled for five days, and the revival was scheduled into the academic catalogue as part of the coursework (Baylor Bulletin, 1923). Alongside a minister, Christian students and faculty worked to win all of the lost to Christ and bring current Christians back on the path of moral righteousness and Christian living. Each year, “most of the lost are saved” and many “are led to be preacher’s and missionaries” (Baylor Bulletin, 1923). The cancellation of class and requirement of attendance at the revival shows the sheer importance of this activity to the campus. The campus did not just exist to fulfill the requirements of an education, but it also sought to convert non-religious students to Christianity. It is not known whether or not the revivals were held to convert non-Baptists, but that is an opportunity for further research. Though, when these students do convert, the B.S.U. is ready to begin to develop them spiritually, and offer avenues for the new converts to begin practicing their faith.

During the 1920s, Baylor’s religious organizations were highly active, serving both the university and the community. Despite this fact, there was little room for non-Baptists to exercise their religious practices within the context of the B.S.U. Baptist students could be involved in a variety of religious organizations, but non-Baptist were on their own to find involvement elsewhere.

Perceived Religious Freedom and Diversity at Baylor

Although the Baptist Student Union at Baylor dominated Baylor’s religious activity in the 1920s, students from many different denominations went to Baylor during this era, making one-third of Baylor’s campus non-Baptist. During 1928, The Daily Lariat seems to boast Baylor’s religious diversity, claiming, “Baylor students are as varied as must have been the tongues at the ancient Tower of Babel” (Neal, 1928, p.1). The article claims that there were fourteen different religious affiliations on campus, according to a report from the Registrar’s office. During 1928, 1,095 Baptists were on campus, 184 Methodists, 57 Presbyterians, 40 Church of Christ, 35 professed Christians that did not claim a church affiliation, 22 Episcopalians, 14 Catholics, 7 Hebrew Synagogue, 5 Lutheran, 3 Congregationalists, 2 Christian Science, and 1 Latter Day Saints, God’s Church, and Greek Orthodox (Neal, 1928). This report suggests that in 1928 there were 1,095 Baptists and 412 students of other religions, and 71 students that do not belong to any church. The report reveals that almost one-third of Baylor’s students were not Baptist, making Baylor look like a religiously diverse institution, statistically. But, just because the statistics revealed a religiously diverse student population did not mean that the campus culture was diverse. The students that were not Baptist but wanted to join a religious organization were forced to do so within the Baptist Student Union, or to remove themselves from campus and serve alongside their church off of campus. Although these alternative opportunities were permitted, they were neither encouraged nor as easily accessible to the students.

Baylor’s yearly bulletin acknowledges the existence of other religious denominations on campus and their work within their chosen churches. The bulletin states, “Full recognition and encouragement are given to the work of students who live in Waco and attend the churches to which they belong” (1928, p.35). Though students were recognized and encouraged to attend the churches that are not Baptist churches, they did not allow the student’s to exercise these practices in any formal religious activity on campus. The Baylor University Bulletin (1928) claims that every woman is “urged to identify themselves [sic] with the organized religious work of the student body” (p. 34). The bulletin does not claim that men have certain expectations; however, the women were compelled, regardless of their religious affiliation, to join in the work of the Baptist Student Union. The Bulletin suggests that Baylor was a religiously tolerant institution; yet, the subculture depicts a Baptist dominated landscape, even though one third of the school’s population was not Baptist during the 1920s.

President’s Views on Non-Baptists

President Brooks gave a speech that reflected upon the role of the Bible in public schools, which reinforced the notion that Baylor was not tolerant toward the idea of other religious groups having a voice in society. Despite the fact that the President’s view does not always reveal the stance of the institution as a whole, the President’s speech was reported in the school newspaper. The article in the newspaper suggests that President’s views were met with “general commendation among faculty and students” (Hunt, 1923). In the speech, Brooks opposed the Bible being read in schools because different denominations would put their own twist on the reading, teaching their doctrine and not Baptist doctrine. Brooks regarded the other groups as “infidel fellow citizens, Catholic neighbor, or Jewish friend” (Hunt, 1923, p.1). The language that Brooks uses towards the groups is friendly and warm, such as “fellow,” “neighbor,” and “friend,” similar to the approach that the Lariat takes in celebrating the religious diversity on campus. Yet, the President only took this language so far before suggesting that their interpretation would be wrong, teaching students a false depiction of the Bible (Hunt, 1923). It appears that Brooks did not have disdain for these people, just as Baylor students did not seem to have disdain for other religious groups. It seems that Brooks does not want the other religious denominations to have equal power within the schools. His stance allowed him to keep tabs on the promotion of other religious viewpoints, even though it limited the Baptists from speaking as well. The overall theme is that Baylor was continuing to hold tightly to its denominational heritage and not partner with other denominations to further the Christian mission.

Appeasing the Other Religious Students on Campus

Just as Brooks maintained friendly regards towards other denominations, the Baptist Student Union seemed to seek a sense unity between the Baptist organization and students of different religious backgrounds. On May, 27, 1921, three religious groups sought to have a joint meeting including: the Methodist City League Union (an organization affiliated with the Methodist Church), the Christian Endeavors (a nondenominational group of students), and the Baptist Young People’s Union Federation. The purpose of the meeting was to create friendlier relations between the overarching Baptist Student Union and the off-campus religious groups for college students (Foster, 1921). The meeting was held on the lawn of the Methodist Home off campus, and representatives from each group took part in speaking, music, and entertainment. President Brooks acted as the keynote speaker and the groups combined to have an orchestra of 400 students (Foster, 1921). This event occurred early in the 1920s and is the only cross-denominational event that was discovered mentioned during the decade. Though the meeting brought the students from different denominations together, interdenominational events were not repeated in the future. As the decade progressed the Baptist Student Union gained momentum within itself and seemed to give little heed to the interests of other religious groups on campus.

After the joint religious meeting in 1921, Baylor’s newspaper fails to make mention of any other religious function happening in regards to college students that is not affiliated with the B.S.U. The vision Boone had for a Baptist denominational religious program became a reality that quickly enveloped all religious activity on campus. As the decade progressed, Baylor became more Baptist focused in regard to its religious organizations.

Conclusion

During the decade of the 1920s, the Baptist Student Union dominated the religious student organizations at Baylor. Its monopoly of efforts stretched across campus and into the community. As the teens turned into the twenties and efforts to create an interdenominational religious group emerged through the Y.M.C.A, Baylor students reacted strongly and forged the way to create a Baptist specific denomination. As is often the case, the students reacted like a pendulum. Instead of settling in the middle and trying to bridge the gap between denominations, they swung in the opposite direction. The campus organization that emerged assumed responsibility for all religious activities on campus. Instead of allowing different religious denominations to work together for the good of the Kingdom, the B.S.U. excluded non-Baptist students forcing them to express their religious sentiments elsewhere. At a time when work could have been done interdenominational, Baylor remained tied to its roots. During this era, Baylor reacted against the nationwide push for interdenominational religious organizations by retreating further into her Baptist niche and creating the B.S.U.

During the 1920s, Baylor boasted its religious diversity but failed to implement religious diversity within student organizations beyond the statistical level. Despite the other religious groups represented on campus, the Baptist Student Union was the only way for religious students to be involved on campus. As long as other religious groups did not threaten them, they were able to exist, but they did not have the same resources offered to the Baptist Student Union. Throughout the twenties, the B.S.U. did valuable work within Baylor and the community. Yet, through its creation, Baylor neglected to give a religious voice to one third of the school’s population. Creating a B.S.U. was not negative overall, nor is it surprising that a denominational institution would like to remain faithful to its religious roots. Yet by dismissing the non-Baptist groups from campus, or subsuming their programs under its structure, the B.S.U. sent the message that there is no place for religious diversity within student organizations.) The approach that Boone and his fellow students took in creating the B.S.U. and making it the umbrella organization for all religious groups on campus failed to take into consideration the interests of other students and excluded them from the religious life of the campus.

References

Baylor University. (1923). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor University. (1928). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Boone, J. (1953). It Came to Pass. Ann Arbor, MI: Edward Brother, Inc. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Clower, V. (1945). Baylor Universities Part in the Origin and the Development of the Baptist Student Union. BU Records: Baptist Student Union Folder. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Copass, M. (Ed.). (1927). The Land of Cotton Round-Up. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Eastland, E. (Ed.). (1923) The Baylor Round Up. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Foster, W.S. (1921 April 14). “Joint Meeting of Young People on May 27th.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved From http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/5686/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Hunt, T.T. (1923 January 20). “President S.P. Brooks Opposes Compulsory Bible Reading in the Public Schools of Texas.” Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/6357/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neal, M. (1928 October 24). “Thirteen Religious Beliefs at Baylor.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/10206/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Ross, E. (Ed.). (1924). The Roundup. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Rouse, M. (Ed.). (1922). The Round-Up. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Student Volunteer Band (1900-1957). Record Book. BU Records: Student Volunteer Band (Box #2, Folder #2). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Student Volunteer Band (1900-1957). Record Book. BU Records: Student Volunteer Band (Box #3, Folder #1). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Wilson, J.W. (1913). History of the Young Peoples Baptist Union of America. Philadelphia, PA: The Griffith and Rowland Press.