by Lisa Perry

In the era of the 1930s, Baylor University was recovering, along with the rest of the United States economy, from the Great Depression triggered in 1929. Tension began and continued to build in Europe as Hitler’s regime gained more and more power and then increasingly more control throughout the continent. In the midst of the wars and rumors of wars, Baylor was by no means isolated from the conversations and debates that raged across the U.S.

In response to reports traveling across the Atlantic, some Baylor students joined the voices of the many young people who rose up in opposition to waging another war in Europe at the expense of young American lives, among other things. The answer seemed to lie in persuading the U.S. government to abstain from the building of munitions stores and conscripting the nation’s young men into the armed forces. The U.S. peace movement joined international coalitions calling for a peaceful resolution to the turmoil of the age. Nearly seventy years after the end of World War II, it is evident that the peace movement was unable to keep the United States from war in the European or Pacific theaters during the 1940s. Though their aims may not have won the day, the peace-keeping efforts put forth by the world’s young people during the era deserve to be examined, and will here be related to the specific efforts and responses of the Baylor community in the years leading up to World War II.

For much of the Baylor community, opposing war was not only a question of political views, but also one of religious morality. The general institutional sentiment was opposed to war on foreign soil. Baylor faculty representatives and guest speakers encouraged students to view pacifism as a moral obligation, with some members claiming religious responsibility for ending war worldwide. The support on campus remained intact as long as peace efforts did not become self-contradicting and remained expressed through peaceful demonstration.

The Baylor Genesis of Anti-war Sentiment

In the 1920s and 1930s, a periodical called the Literary Digest circulated in the United States. The Literary Digest was famous throughout the country for its publication of poll results gathered from participants across the nation. It was particularly famed for accurately predicting every US Presidential race from 1916 until it erred in the 1936 election when it named Landon the winner over Roosevelt. The polls ranged in topic but were generally thought to be reputable and informative (Landon in a Landslide, n.d.).

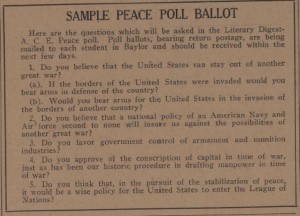

In its third issue of 1935, the Baylor Lariat (the Baylor student newspaper) reported that the Literary Digest—Association of College Editors would soon be distributing a peace poll to students at Baylor and 115 other college campuses (Smith, 1935, February 12). Students would receive a copy of the poll through the campus mail (Smith, 1935, January 8). The Lariat informed students of the questions to be asked on the poll and in a subsequent issue, published student responses examining both sides of each query addressed in the poll.

The poll questions centered around respondents’ willingness to engage in military activity defensively or offensively (whether foreign or domestic invasion), government policy regarding naval and air force development as war prevention, and whether the government should be able to conscript wealth as a supplement to war funding. The student responses were given in a thoughtful and balanced manner so as to provide the general student readers with some idea of the factors that played into the issues at hand (Smith, 1935, January 10).

As the poll was distributed, returned, and analyzed by the Literary Digest, the Lariat faithfully kept its readers abreast of the poll’s progress. The results, published in February 1935, indicated that Baylor respondents fell in line with the popular sentiments reported from across the country. The strong majority of Baylor students (83%) were of the opinion that the U.S. could stay out of war. Ninety-one percent of Baylor respondents indicated that they would bear arms in the event of a domestic invasion. Conversely, only 13% of Baylor respondents said they would participate willingly in the invasion of another country. Sixty-six percent indicated that they did not believe developing a superlative navy and air force would prevent future instances of U.S. participation in war. Ninety-seven percent of Baylor respondents favored “government control of the munitions industry” (Smith, 1935, February 12, pg. 1). Finally, 85% of Baylor respondents to the Literary Digest voted in favor of the “universal conscription of wealth in times of war” (Smith, 1935, February 12, pg.1). On the question of whether or not the U.S. ought to join the League of Nations, the respondent population from Baylor was relatively ambivalent with 53.4% of respondents in favor of joining.

The Baptist Student Union Takes Up the Cause

In October of 1935, eight months after the publication of the Literary Digest peace poll results, the Lariat published an article titled “What About War?” The article served as a precursor to the evening’s Baylor Religious Hour gathering, which was to address the nature of war and the need for peaceable resolution to international conflict. In the article, the author notes,

We recall that last spring no attention was given to the nation-wide student protest against war, although Baylor students voting in the Literary Digest peace poll gave a decided majority in favor of the outlawing of war, and in spite of the fact that this is a Christian institution and therefore is fundamentally opposed to war. That in itself was most unfortunate. (Reaves, 1935, October 9)

The article went on to encourage students to attend to the efforts of Paul Geren, B.S.U. president, and the rest of the organization in its attempt to shed light on the national peace movement coming alive on American college campuses and around the world.

Up until this point, the Baylor community’s conversation regarding pacifism was compartmentalized to political stances. This unnamed author brought the conversation into the realm of moral and religious obligation with his or her seemingly simple statement. Being opposed to war was, apparently, the correct and Christian stance to assume. Geren’s interactions with the B.S.U., subsequent commentary from the school newspaper, and a number of guest speakers later hosted on the Baylor campus continued the theme of morally and religiously-motivated pacifism.

The Lariat reported the general content of Geren’s message, saying that the student leader had proclaimed to the assembly that war was a lie. In essence, he highlighted the ways in which the pursuit of war was not motivated so much by noble causes as by a number of political agendas. He pointed out that war caused Believers on both sides of the struggle to invoke the name and blessing of God as soldiers marched to uncertain fates in the military ranks.

As the results of the Literary Digest poll indicate, there already existed at Baylor a majority anti-war sentiment among the student population. However, as no specific action had been taken on campus until Geren’s B.R.H. address, the sentiment was perhaps not necessarily “active.” The tides were beginning to change within the Baylor student body in regards to the pursuit of peace in international affairs. The catalyst for Baylor’s participation in the national peace movement throughout the late 1930s moved the B.S.U. council to action a month after Geren’s initial address.

Localizing a National Movement

Milton Miller, described by the Lariat as a Baylor student from Brooklyn, New York, carried the torch of the national peace movement to the members of the B.S.U. council on Monday, November 11, 1935. He described to the council what the peace movement was doing on American college campuses across the nation. Miller shared specifics of what other student organizations were accomplishing in such a way as to convince the B.S.U. council to consider founding a similar organization on the Baylor campus. The motion was put forward and approved the same night (Reaves, 1935, November 13).

On Wednesday, the 15th of November, the Lariat reported that the B.S.U. council moved to pursue the establishment of a peace-advocating, anti-war organization on the Baylor campus and were moving to assemble a student-faculty committee to reach that end (Reaves, 1935, November 13). Another article in the same issue commented on the movement for world peace on campus:

It is well that a religious body has assumed the responsibility to promote the move at Baylor. A peace not founded on religion—the one thing all men hold in common—will not last… Baylor can make a very valuable contribution to the cause of peace; that contribution should be the placing of God and his will into the peace and life of the world and its people. (Reaves, 1935, November 13, pg. 2)

Once again, the student newspaper advocated that the foundational element of international peace was best found in a faithful and religious organization.

After the Christmas holidays, the B.S.U. continued to pursue the establishment of a peace-promoting organization on campus. The first meeting of the official Baylor Council of the International League for Peace occurred on Tuesday, March 24, 1936, in the Memorial Dormitory. Matthew Dawson was elected chairman of the council and Sam Stringfellow, a contributor to the Lariat, was elected vice chairman. The stated purpose of the council was to publicize congressional activity as it pertained to their cause and acquire signatures to be added to the international petition for peace (Reaves, 1936, March 25).

The Lariat reported that not all of the Baylor constituents were readily endorsing the peace movement on campus. Those who felt unsettled about the activities of the new campus organization were not necessarily in disagreement with organization’s mission or aim. They were more likely to be wary of “peace demonstrations” devolving into riots (as had been the case at other institutions during the same time). The Lariat voiced its collective opinion of the movement and the council in affirming its full support as long as the methods of the peace movement remained peaceful in and of themselves (Reaves, 1936, March 25). With this commentary from the Lariat and the statistics from the Literary Digest poll, the overall picture of student orientation towards the peace movement is one of support though not necessarily active participation.

Religion at Baylor and its Relation to Pacifist Sentiment

As the Baylor Council of the International League for Peace continued to meet on a weekly basis, they entertained speeches from a number of students, faculty, and guest speakers involved in the national peace movement. One speaker of particular note was Professor F. E. Burkhalter, head of journalism studies at Baylor.

(Courtesy of the Texas Collection)

Burkhalter addressed the peace council on April 9th, 1936. The headline of the Lariat article the next day read “Burkhalter Declares Christian Education, Not Peace Pacts, Will Terminate Wars” (Stringfellow, 1936,

April 10). The message, as paraphrased by Stringfellow, described contemporary warfare as a means of earning profit for arms manufacturers, bankers, and others. Burkhalter enumerated the cost of war in the terms of finances and lost lives (1936, April 10). He then declared,

…war, as fought today is neither glorious, Christian, desirable, civilized, profitable (except to the munitions manufacturers), nor necessary today… the journalism professor (Burkhalter) pointed to the education of people along Christian lines of though [sic] as the only permanent assurance of peace. (Stringfellow, 1936, April 10, pg. 2)

Generally, Burkhalter’s message contained the idea that war was immoral and irreligious not only because of the destruction and loss of life, but because of the corruption of munitions manufacturers, the interest of politics, and the presence of bribes in war dealing. Burkhalter suggested the best solution was the spread of Christian religious values and morality to abate the warmongering.

Interestingly, Burkhalter’s address to the peace council was not the first time he shared that particular message. The Lariat explained that Burkhalter had delivered a similar speech on several occasions as many as two years before addressing the Baylor council for peace in 1936. The message was so well received by the initial, local audience that word of it spread to the president of the Baptist General Convention of Texas (BGCT). Burkhalter was then asked to share the message at the BGCT state meeting in November, 1934. He was invited to an encore presentation at the BGCT meeting the following year (Reaves, 1936 April 9). This endorsement of Burkhalter’s sentiments in the religious body of the BGCT provides a substantial link to Baylor as an institution.

Several associations and organizations existed as precursors to the BGCT. The earliest of these was the Texas Baptist Education Society, which was named in Baylor’s charter as the appointee of members to the Baylor Board of Trustees. Eventually, the Texas Baptist Education Society would become part of the Baptist State Convention (the precursor to the BGCT). When the nation struggled through the aftermath of the Civil War, “the Baptist State Convention never wavered in its support for Baylor, both moral and financial” (McBeth, 1998). As a controlling entity in the administrative and financial life of Baylor, the BGCT and its endorsements represent the interests, functions, and ideals of the university as an institution of higher learning.

There is a circular relationship between the interests of the BGCT, Baylor as an institution, and Burkhalter as a representative of Baylor to the BGCT. The strength of support offered to Burkhalter’s message encouraged the idea that these three parties shared a like-mindedness in regard to peace being attained through Christian education and the advancement of religious morality. Burkhalter’s message is not exactly congruent with the mission of the Baylor council for peace. The local and associated Baylor community shared the sentiment that war was not the appropriate resolution to the conflict of the times.

An Epilogue for the Baylor Council for Peace

One significant pillar of the national peace movement in the United States was the national student strike day in April. In 1935, 125,000 students across the United States participated in the student strike day, though none of those students were in the South (Reaves, 1935 November 13). Early in its existence, the Baylor Council of the International League for Peace voted not to participate in the national strike, but advocated for and were allowed to promote their cause in a chapel service on April 23, 1936 (Stringfellow, 1936 April 17). The strike, held April 22, 1936, drew over 300,000 students out of their classes in a movement that spanned the entire nation (Reaves, 1936 April 23). On that day, a number of Baylor students approached various members of the council for peace on campus and asked as to the reason why Baylor was not participating in the strike.

The Lariat explains, “Campus reaction to the no-strike vote of the Baylor student peace council seems to indicate that perhaps the council and the Lariat misinterpreted the sentiment of the student body. If so, we apologize” (Reaves, 1936 April 23, pg. 2). The Lariat article “Baylor’s Attitude on War” goes on to explain that the council did not believe there would be enough active interest for successful campus participation in the strike, and therefore voted it down. The council witnessed a significant peak in the anti-war sentiment on campus during the observation of “peace week” during 1936.

Although the Lariat records that the peace council remained active in the Baylor community, specific focus eventually expanded to pay more particular interest to the national efforts at promoting peace in the United States. The peace council surfaces as officer elections and a few special events take place on campus, but the narrative became less and less consistent as the nation drew nearer engaging in the second World War.

What began as a series of Lariat stories on the formation of a new campus organization became a chronicle of the efforts of Baylor students to promote peace on the international level. The anti-war majority stance in the Baylor community and the assumed ties between religion and preservation of international peace manifest in the activities of the Baylor Council of the International League for Peace. Though the valiant efforts of students across the United States were not able to keep the nation from engaging in war, the peace movement provided a trial to test the values and interests of the Baylor community revealing a strong preference for pacific methods for resolving international conflict.

References

Ferguson, J. (1936 March 25). “Baylor peace council to quiz congressmen on war policy; Matt Dawson is leader.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections. baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/34954/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

“Landon in a landslide: The poll that changed polling”. (n.d.). History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web. Retrieved from http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5168/ . George Mason University.

McBeth, H. L. (1998). Texas Baptists: A sesquicentennial history. Dallas, TX: Nortex Press.

Provence, H. (Ed.). (1937 February 11). “Oratory contest of peace council will be held next week: Sixteen students seek prize of $15; date set back one day.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/ collection/lariat/id/35574/rec/2. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1935 November 13). “Peace and the campus.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/ collection/lariat/id/35286/rec/9. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1935 November 13). “Student organization joins move for peace: Milton Miller of New York addresses B.S.U. and formulates Baylor plan.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/ collection/lariat/id/35286/rec/9. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1936 April 9). “Burkhalter to speak on case against war.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/ collection/lariat/id/35306/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1936 April 23). “Protest against war scheduled for chapel: Mat Dawson will preside today at peace ceremony; students to speak.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/34903/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Smith, B. (1935, January 8). The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/38334/rec/1

Smith, B. (1935, January 10). “Baylor students discuss questions in Literary Digest A.C.E. Peace Poll.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/ compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/38369/rec/1

Smith, B. (1935, February 12). “Good Morning!” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/38379/rec/1

Stringfellow, S. (1936 April 10). “Burkhalter declares Christian education, not peace pacts, will terminate wars.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections. baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/35006/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Stringfellow, S. (1936 April 17). “Proposed student strike voted down by Baylor peace council.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/ cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/35594/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.