by: Lauren Gray

Access at Baylor 1931-1940: The Student Union Building Campaign

The Bill Daniel Student Center is an integral component of student life and culture at Baylor University. The building, also known as the Student Union Building or SUB, is a common meeting place on campus and offers a wide variety of services for students. Walk through the SUB at any given time of day, and you will immediately appreciate the numerous ways in which students, staff, and faculty utilize the spaces in this building. Come by during lunchtime, and you will see hundreds of students in line for a variety of fast food options. Between 3 and 4PM on a Tuesday, drop by the Barfield Drawing Room, where you can enjoy a float at Dr. Pepper Hour and mingle with members of the Baylor community. Venture down to the basement, and you will find the Baylor Gameroom equipped with a five-lane bowling alley. Today, Baylor proclaims the SUB to be “the heart of the campus” and states that it “provides a space to relax, study, and participate in activities that build an enduring loyalty between members of the Baylor community and to the university itself” (Baylor Student Union Homepage). With all of the day-to-day activities and campus traditions/events that are held in the SUB throughout the school year, it is hard to imagine a time at Baylor without this building.

Need for Student Union Building

In the 1930’s, an idea was sparked that Baylor needed a social center. In 1936, “Dr. K. H. Aynesworth led a group of Baylor ex-students in the organization of the Baylor Centennial Foundation for the purpose of securing funds over a period of years, so that the University’s Centennial could be commemorated by the gift of a building in which students, ex-students, and friends might enjoy the spirit of campus fellowship” (Round Up, 1945). Aynesworth was named President of the Foundation and immediately began efforts to raise alumni support.

Reaching Out

In 1938, Baylor began sending a monthly magazine/newspaper to Baylor alumni and friends called The Baylor Century. Nell Whitman Gurley, a professor at Baylor and secretary of the Baylor Centennial Foundation, wrote an article in the March 1938 edition of The Baylor Century titled “Why the Union Building Should Be Built Now.” In this article, Nell passionately articulates the urgent need for a Student Union building at Baylor. She writes:

“We give [students] class rooms, libraries, laboratories, gymnasiums, and chapel hours; we schedule and regiment their activities during those hours of the day when goals of activity take every form that a university curriculum necessitates. But what can we offer students during those minutes or hours of the day and evening when they relax? Nothing! Nothing! The drug store, picture shows, and other places are sought during leisure.”

Gurley touches on the fact that Baylor had over 2100 students yet only 901 of those students lived on campus. This leaves the other “1199 students on the campus from eight to fourteen hours a day without the facilities of a rest room, lockers for coats and galoshes, without a cafeteria in which to be served wholesome food at a nominal price, without any facility for recreation or rest when either ill or well” (Gurley, 1938). She continues, “there is no medium… through which to meet the rest of the new student body except during the routine hours of the classroom” (Gurley, 1938).

At Pat Neff’s request, Gurley gave a speech to the entire study body about the work of the Baylor Centennial Foundation. Her notes give insight into the motivations and argument for why Baylor would be enhanced with the addition of a student union. Gurley quotes Aristotle who said, “The end of labor is to gain leisure” (Gurley, handwritten notes). She notes “leisure is not a bad thing” and even that “today’s student, because of economic changes, is due to have more leisure” (Gurley, handwritten notes). That being said, Gurley stresses that “how [a student] uses [leisure time] is of essential importance” (Gurley, handwritten notes). Gurley discusses how most “leisure time is spent in passive, sensory leisure” such as watching movies, listening to the radio, drinking, and “just plain loafing” (Gurley, handwritten notes). She argues that a student union building would help cultivate a more cultured environment with more stimulating forms of leisure (Gurley, handwritten notes). Large portions of Gurley’s notes are devoted to how student unions are being utilized at prestigious institutions around the country. Brown has used its Student Union to hold workshops, “lending encouragement to creative hands” while “Rochester, Michigan, and Texas… are giving specific training in social and community” affairs (Gurley, handwritten notes). Cornell “stimulates fellowship through informal teas held for women four times per week,” and Purdue houses several clubs under the Union Advisory Council within its union building (Gurley, handwritten notes). Gurley states that “the union building for Baylor’s campus can be built according to her individual needs” and notes that she has “only sighted these instances at other campuses to show… how the union building has become one of the greatest factors in the modern U. campus” (Gurley, handwritten notes).

Gurley makes it clear this space will benefit former students as well. At that time, there was no place for alumni to congregate during homecoming or commencement. Those who came back would have to find places around Waco to meet without “any organized, effective coordination of the alumni as a whole in service to Baylor University” (Gurley, 1938). Even as a faculty member concerned with academic affairs, Gurley agreed, along with so many others involved in the Foundation, that building the student union was essential for Baylor University and its students.

Student Wishes & Union Buildings Across the Nation

In the December 1938 edition of The Baylor Century, a few prominent Baylor students were given the opportunity to share their Christmas Wishes for Baylor with the 1945 Centennial in mind. Most all of the students were appreciative of the wonderful qualities Baylor already possessed and only saw their wishes as adding to Baylor’s greatness. Many spoke of the need for multiple buildings on campus, but the need for a Union building was a common theme throughout. Baylor Chamber of Commerce President, W. J. Wimpee expressed “when Baylor’s Centennial Year is celebrated we, as alumni, would like to be able to point with pride to a new union building” (Baylor Century, 1938, December). Wimpee speaks for fellow students when he said, “we feel that social activities connected with the institution are lacking, but with the completion of a Union building we believe that social functions should match, stride for stride, developments along all other lines” (Baylor Century, 1938, December).

Pi Gamma Mu President Charles Woodward acknowledged Baylor’s “remarkable progress over the last few years” and wanted to see Baylor build upon the “foundation of Christian training of the mind and the body [that] has been well laid” (Baylor Century, 1938, December). Sophomore class president Warner Brock, along with the wish of a new science building believes what is “needed even more, is a Union building in which social activities, such as those carried on in other universities, may be held because this would truly make it a social center” (Baylor Century, 1938, December).

In a 1939 brochure, President Pat Neff echoes these student sentiments stating, “among the things sorely needed at Baylor University for the efficient ongoing of the institution is a Union building. It will add substantially to the happiness and well-being of the entire student body” (1939 Student Union Building Brochure).

At this point, students, faculty, and the administration were unanimous in their support that the Union building was a critical component in order for Baylor to remain a prominent university. The only issue was how to get the money for the building and convincing an audience of alumni to show their support.

Fundraising Efforts and Alumni Support

Through the end of the 1930s, Baylor continued to press her alumni for financial support through issues of The Baylor Century and a statewide fundraising effort led by the Baylor Centennial Foundation. Efforts for the Student Union building had been in place long before Nell Whitman Gurley’s article was published. In 1937, “former Baylor students, from all over the Southwest… formed and had incorporated the Baylor Centennial Foundation for the purpose of raising funds for a building or buildings which would be presented to Baylor on her one-hundredth anniversary as a gift from her former students” (1939 Student Union Building Brochure).

Fundraising goals were extensive and involved the efforts of thousands of Baylor “exes” pulling together to raise the necessary funds (Baylor Century, 1939, April). An article published in the April 1939 edition of The Baylor Century titled “New Union Building to Be Gift of Baylor University Ex-Students Will Provide Needed Social Center for Entire University” shed light on the action that was being taken to make the vision for the student union a reality.

Members of the Baylor Centennial Foundation formed separate organizations of former Baylor students in cities across the state to raise the $123,000 that was needed in order to start construction by September 1. The urgency of the matter was crucial because “an anonymous gift valued at $42,000” would be lost if this were not to happen (Baylor Century, 1939, April). The article further details the recent campaign leadership and committees formed to organize these efforts.

Headquarters for the campaign were set up at Baylor, and the Century article states that “the new Union building campaign has gained rapid momentum during the past three weeks of organizational effort. The enthusiastic and cooperative spirit of ex-students in all parts of Texas for the project has been gratifying” (Baylor Century, 1939, April). Although funds for the building were to be raised across a ten year period, the efforts had “become of such outstanding importance to the campus and the general well-being of the University that Centennial Foundation heads and others strong in the support of Baylor have urged a more concentrated campaign period” (Baylor Century, 1939, April).

In order to convince ex-students to pledge their support, the article noted that other universities had already established union buildings and that “such a campus center, educators agree, is essential to the growth and development of the well balanced student of this day” (Baylor Century, 1939, April). It also emphasized that the space would be beneficial for both current and former students, “strengthening the bond between the University and its vast family of graduates” and would “symbolize the active participation and interest of these graduates in university affairs” (Baylor Century, 1939, April).

Union Building Campaign Materials

Several promotional materials were made for the Union Building Campaign that reinforced why the building was necessary, what it would provide for students, and what funds were still needed to start construction. One of these materials was a 1939 booklet titled, “For Tomorrow We Build” that goes into detail about such matters. The booklet begins with a brief history of Baylor, noting her beginnings at Independence and then sheds light on what Baylor has since become. The booklet mentions that Baylor’s enrollment has grown to over 2,300 students and that there are over 35,000 ex-students (1939 booklet For Tomorrow We Build). It builds upon Baylor’s recent successes—the completion of almost four new buildings, an increased endowment, a doubled enrollment, and the elimination of debt (1939 booklet For Tomorrow We Build).

Once again, the argument is made that both former and current students need a social center, especially since so many students live off-campus. It argues, “colleges throughout the country in recent years have met progressive social changes and have equipped themselves to teach their students not only the rules of intellectual living, but the fine art of social living as well” (1939 booklet For Tomorrow We Build). It argues that students should have the opportunity “to appreciate the stimulation of wholesome social contacts and share in experiences which make for fuller, richer living” (1939 booklet For Tomorrow We Build).

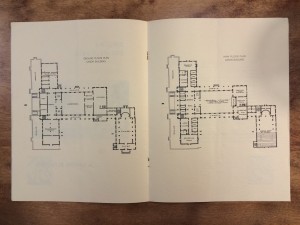

The booklet also takes great care in showing what the union building would look like upon completion. There is a detailed floor plan, as well as a list of its potential uses. The amenities would include a reception room “to fill a long-felt need in accommodating visitors, parents, friends, and ex-students during short visits to the campus”, a recreation room, a reading room, “numerous offices for student organizations, faculty club rooms, and a permanent headquarters for ex-student activity”, a cafeteria to “provide wholesome, healthful food”, banquet rooms “for the serving of special dinners”, a student book store, a fountain, and a university post office to “complete the miniature city” (1939 booklet For Tomorrow We Build).

The last few pages of the booklet draw upon the emotions of the reader to ask for their generous monetary support. It emphasizes that “completion of the Union Building will improve materially the University’s standing” and that “it will be a living, vibrant emblem of the social as well as intellectual opportunities [to offer] their sons and daughters” (1939 booklet For Tomorrow We Build).

A 1939 promotional pamphlet titled, “Student Union Building: To Be Gift of Baylor Ex-Students To their Alma Mater,” discusses one of the most critical components of the campaign. The fundraising effort “is a former students’ movement—the first concerted movement ever attempted under the auspices solely of Baylor men and women” (1939 pamphlet). The campaign stressed to former students that “it is to be YOUR building for you and Baylor students” and it will be “for the use of every student, past, present, and future—for the social, cultural, and religious advantages which such a building can furnish” (1939 pamphlet).

Conclusions

Due to the efforts of dedicated alumni and other resources, construction of the Union Building began in 1940, but work was halted due to involvement in WWII. After the war was over, construction was able to resume, and by 1947, the Union Building was opened and later included “lounges, recreation rooms, a cafeteria, a university bookstore and post office, fountain, barbershop, beauty shop, reception rooms, and club rooms for meetings and activities of the social organizations on the campus” (Round Up, 1945).

Today, the Bill Daniel Student Center represents a need fulfilled. The success and scope of the Student Union Building campaign was a testament of how great that need was felt, especially by former Baylor students. In the 1930s, students, faculty, and staff were searching for access to amenities they lacked. There was a need for a place that would accompany Baylor’s academic focus and contribute to the enhancement of student life.

Nell Whitman Gurley argued that “The Union building is to be symbolic of the unified Baylor Spirit… a message to the outside world which will tell the fullness of the life of the student body which will pass through her halls for the next hundred years” (Gurley, 1938). Today, the Student Union Building is in fact a testament to Baylor spirit and to all of the students who have loved Baylor so dearly.

REFERENCES

Baylor University (n.d.). Student union home page. Retrieved from http://www.baylor.edu/studentactivities/studentunion/

Gurley, N. W. (1938 March). “Why the union building should be built now.” The Baylor

Century. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

[Typed excerpt from Baylor Round Up]. Student Union Subject File. The Texas Collection,

Baylor University, Waco, TX.

[Handwritten notes on Mrs. Davis Gurley Department of English Letterhead]. Student Union

Subject File. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

(1938 December). “Christmas wishes.” The Baylor Century. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

[1939 Student Union Building Pamphlet]. Student Union Subject File. The Texas Collection,

Baylor University, Waco, TX.

[1939 booklet For Tomorrow We Build]. Student Union Subject File. The Texas Collection,

Baylor University, Waco, TX.

(1939 April). “New union building to be gift of Baylor university ex-students will provide needed social center for entire university.” The Baylor Century. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

[1939 Student Union Building: To Be Gift of Baylor Ex-Students To their Alma Mater]. Student

Union Subject File. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.