By Katy Flinn

The stock market crash of 1929 sent America into the Great Depression, leaving many jobless and hungry. College enrollments may have increased or decreased during the Great Depression. Thelin (2011) suggest that enrollments increased due to individuals not knowing other options or having other options due to job scarcity. However Baylor President Pat Neff believed nationwide enrollments to be going down due to financial privations (Neff, 1933). He was very proud of Baylor’s accomplishment of increasing enrollment throughout the decade despite the country’s hardships, and he and others at Baylor made great strides to see that happen. In a chapel service in 1933, Neff proclaimed “in spite of the depression [we have] the largest Freshman Class that ever entered Baylor in all its triumphant history. While attendance at most institutions have decreased, we have increased.” The growth was not solely due to the university faculty and staff; contrarily, students were highly involved in it. The successful institutional promotion that occurred during the 1930s making Baylor and the value of a Christian institution known in the community, country, and the world was largely due to the involvement of students.

Baylor in the 1930s

In the 1930s Baylor began and further developed a series of outreach efforts designed to increase awareness, finances, and interest in attendance through events targeted at particular audiences. Baylor reached the community through public campus events. Theatre performances and athletic events were open to the community, but the most prominent form of outreach towards potential students was the Baylor Field Day, a day of showcasing the university to local high school seniors (Neff, 1938). These days involved dozens of students who played a crucial role in showcasing their university. The other main form of outreach during the 1930s came through talented quadruplet women, known as the “Keys Quads”, who made many public appearances on campus, in the community, and throughout the country.

Baylor Field Days

One of the ways students were involved in institutional promotion was the Baylor At Home Day, which came to be known as Field Day. Dean of Women Lily Russell and the 14th District of the Women’s Missionary Union started it in 1933 to promote Christian education and “interest the young people in Baylor University” (Secretary Committee, 1933). The first Field Day occurred May 6, 1933. A letter of invitation sent to high school seniors around the region reads,

Your presence is cordially requested at an “open house” at Baylor University on May 6 in honor of the high school seniors of this district. The programs will include visits to places of interest about the campus, a free barbeque lunch, and a pass to the Baylor-Texas baseball game that afternoon. Instructions for registration as well as the day’s schedule will be published in the Baylor Lariat to be distributed in Waco Hall.

At the 1935 Field Day, 82 Baylor students of all years volunteered their day to help conduct visitors about the campus (Russell, 1935). Hundreds of high school seniors were in attendance. The junior female volunteers spent the day in the residence halls showing around anyone that approached and talking about their experience in the halls (Russell, 1933). The student editors of the Lariat made a special issue in honor of the guests that student guides were encouraged to distribute. Student guides were instructed to make the guests feel at home, watching out for the group and pointing out the drinking fountains in all the buildings (Directions for the Reception Committee). Other student volunteers manned information booths around campus.

Students were not only involved as tour guides but also through participation various campus organizational showcases. These showcases and activities across campus during Field Day varied but were numerous each year. Prospective students could watch the Little Theatre’s one act play, the Latin department’s skits, the law department practice court, or the Spanish fraternity program (Lily Russell Papers). They could visit the Baptist Student Union to talk to members or the Browning room to learn about Texas history. In 1937 the day included a motion picture about Baylor and a message from Baylor students that had won high honors in intercollegiate forensics contests (Waco High Schoool Radio, 1937). The schedule allowed seven time slots of thirty minutes each for prospective students to have conferences with professor representatives of the various departments, and the Baylor students were helpful in escorting the students to the different locations and talking about their majors (Secretary Committee).

Student organizations involved varied year to year, but the 1935 Field Day showcased theGirl’s Choral Club, the Glee Club, the Baylor Little Theatre, the Golden Wave Band, and volunteer tour guides (Field Day, 1935). The 1937 Field Day featured the A Cappella Choir and the Baylor String Quartet. The baseball game was often a popular portion of the day. The student athletes were able to show off their talents to over 1,300 visitors (Russell, 1936). The Baylor students were generous to give their time to these days. The skills they possessed in the arts, academics, or athletics amused and intrigued local seniors. These students that were part of the various showcases of talents through the arts and athletics provided entertainment. The day was not only an informative day but also a fun one. It gave the prospective students a feeling of being welcome and created a better connection to the university as they laughed along with plays and gasped along with fans at the games. Photo courtesy of Baylor University Texas Collection.

The Baylor staff wanted as many prospective students as possible to come to these days. In order to encourage attendance, any high school that had 100% senior attendance would receive a Round Up, the Baylor annual (Lily Russell Papers). At the 1934 At Home, 28 high schools came and 11 of them had 100% senior attendance. In a letter to Abbott high school in 1935 Russell said, “I trust that you and your students will enjoy the book and that it will be the mean of interesting students for many days to come to Baylor University.” The Round Up was a great promotional tool made by students- yet another way students were involved in the promotional process.

Time after time throughout the 1930s Baylor personnel proclaimed the value of a Christian education. A “priceless plus” of coming to Baylor was this Christian atmosphere and training. The secretary committee explained, “‘seeing is believing.’ Our young people will believe in our Christian schools when they see them at work.” The goals of the At Home days were to “further the great cause of Christian education and at the same time give our seniors a real treat by bringing them to visit our leading Baptist institution” (Secretary Committee, 1933).

Hundreds of students were involved in Field Days throughout its early years, and that involvement was beneficial for both Baylor and the students. Student participation was crucial for Field Day success. These students were able to personally convey Baylor and its impact to prospective students, making them feel welcome on campus and answering any questions. Being able to make this personal association better helped prospective students envision themselves there. In return, Baylor students were able to take ownership being at Baylor, actively participating in furthering it. This strengthened student endearment toward Baylor as they thought through what positive messages to convey to students about their time on campus. The Field Days allowed students to develop leadership and social skills as well.

Backstory of the Keys Quadruplets

Hundreds of students were involved in the Field Days that promoted Baylor to the local community, but four girls played a large role in bringing the University to national and international attention through the carefully crafted promotional skills of Pat Neff. Leota, Mary, Mona, and Roberta Keys were born in their home in Hollis, Oklahoma in the middle of the night on June 4, 1915 (StoryCorps, 2007; Fiedler, 2012). Their entrance into the world shocked their parents, who were only expecting one baby, and fascinated the world. This was a time before fertility drugs and multiple births were far less common (Fiedler, 2012). Hundreds of people came in from around the country to see the quadruplets, and former President Teddy Roosevelt even sent a congratulatory telegraph (Fiedler, 2012). From the age of nine months they were on display at the Oklahoma State Fair, making 25 cents per onlooker. The girls simply sat and played with their dolls while riveted crowds filed through (StoryCorps, 2007). Parents Flake and Alma Keys received many offers from circuses, Hollywood, and other performing and showcasing groups, but the traditional Baptists refused, wanting their daughters to grow up “normal” (Fiedler, 2012; Blodget et. al., 2007). They were the first American quadruplets to live to adulthood (Blodget et. al., 2007).

Photo courtesy of Baylor University archives.

Photo courtesy of Baylor University archives.

Growing up, the girls exhibited musical talents, and they all learned to sing and play the piano and saxophone (Fiedler, 2012). They developed a forte of singing as a quartet, making them more of a sensation than they already were; not only were they four girls that looked and dressed alike, but they also were talented musicians. President Neff first met the Keys Quads at a program in Oklahoma in 1932 (Blodget et. al., 2007). When he learned that they were church-going Baptists that would finish high school in the spring of 1933, he recognized the opportunity they could be if they attended Baylor (Blodget et. al., 2007). Neff persuaded the Board of Trustees to give the girls full scholarships (Blodget et. al., 2007).

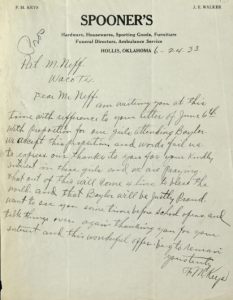

Neff had discussed attendance at Baylor with the girls when he met them, but after he got approval from the Board he sent letters to the family. In February he sent the girls a letter offering them full scholarships (Neff, 1933). In June, after attending their high school graduation, Neff sent a letter to their father, Flake, explaining six features included in the offer (Blodget et. all, 2007; Neff, 1933). First, each of them would be given full scholarships, including the school of music. Second, they would be housed in “one of the very best rooms in the Memorial Dormitory,” which was “one of the best in the state” well equipped with all of the modern conveniences (Neff, 1933). Third, the Keys would not be expected to pay any of the fees or taxes required by most students. Fourth, their meal plan was covered. Fifth, they would not have to buy books, and sixth, in conjunction with a shop in Waco, the girls would each receive “a nice dress, hat, pair of shoes, and a pair of silk hoes” (Neff, 1933). He then went on to explain why Baylor was a great school and how the girls would get a quality education, “not only in books but in the more valuable things that girls get while attending school, out of the atmosphere and ideals of the school attended” (Neff, 1933). The Keys family was overjoyed at this generous offer. In a letter back to Neff, Flake Keys expressed, “we accept this proposition, and words fail us. [We] express our thanks to you for your kindly interest in these girls, and we are praying that out of this will come four lives to bless the world and that Baylor would be justly proud” (Keys, 1933).

Neff had discussed attendance at Baylor with the girls when he met them, but after he got approval from the Board he sent letters to the family. In February he sent the girls a letter offering them full scholarships (Neff, 1933). In June, after attending their high school graduation, Neff sent a letter to their father, Flake, explaining six features included in the offer (Blodget et. all, 2007; Neff, 1933). First, each of them would be given full scholarships, including the school of music. Second, they would be housed in “one of the very best rooms in the Memorial Dormitory,” which was “one of the best in the state” well equipped with all of the modern conveniences (Neff, 1933). Third, the Keys would not be expected to pay any of the fees or taxes required by most students. Fourth, their meal plan was covered. Fifth, they would not have to buy books, and sixth, in conjunction with a shop in Waco, the girls would each receive “a nice dress, hat, pair of shoes, and a pair of silk hoes” (Neff, 1933). He then went on to explain why Baylor was a great school and how the girls would get a quality education, “not only in books but in the more valuable things that girls get while attending school, out of the atmosphere and ideals of the school attended” (Neff, 1933). The Keys family was overjoyed at this generous offer. In a letter back to Neff, Flake Keys expressed, “we accept this proposition, and words fail us. [We] express our thanks to you for your kindly interest in these girls, and we are praying that out of this will come four lives to bless the world and that Baylor would be justly proud” (Keys, 1933).

The Keys Quadruplets and Baylor

“Bless the world and make Baylor proud”, they did. The Keys quadruplets played a crucial role in bringing Baylor national and international recognition. The Keys enrolled as the first quadruplets at Baylor in September of 1933 as members of the Class of 1937. American Airways flew them to Waco from Oklahoma for free (Fiedler, 2012). Roberta, Mona, Mary, and Leota “were good students, and proved that every dollar of their scholarships had been well spent by helping boost Baylor in a variety of ways” (Fiedler, 2012). The Keys family knew why Neff had given them such generous offers to attend Baylor. Roberta remarked, “He saw the value of publicity. He was a publicity fiend, and thank goodness for that” (Blodget et. al., 2007). They never saw their role with the university as exploitation. The quadruplets were used to being on display. Roberta remembered, “We never knew anything else. Wherever we were, we lined up and people took pictures. We said hello and went on our way” (Karkabi, 2005). Neff’s offer to the girls on attending Baylor was mutually beneficial. “It was the Depression, and my father was already going under financially,” Roberta remarked. “We would never have been able to go to college if President Neff hadn’t been long on publicity.” For them it was a remarkable opportunity to get a quality education and serve the university in which they studied. The young women enjoyed performing; in fact, they continued as a quartet post graduation until Mona got married (StoryCorps, 2007).

The girls performed at the opening ceremony of each Field Day during the time of their enrollment, a selling point Baylor used when advertising for these events (Lily Russell files). The invitations read, “Baylor’s famous Keys Quadruplets will be presented” (Russell, 1935). Nearly everyone in the community knew who they were and had likely seen them perform, but the quadruplets’ reach bounded far beyond McLennan County (Fiedler, 2012). The Keys women traveled across Texas with Neff promoting Baylor (Fiedler, 2012). Neff would go on tours to spread the name of Baylor, in hopes of both gaining students and financial support. He used the promise of a performance by the famous Keys Quadruplets to attract people then spoke about “the great cause of Christian education” (Secretary Committee, 1933). He explained to audiences the effect and benefit a Christian education can have on a student and a community, then explained how well Baylor was doing just that. (Blodget et. al., 2007). Leota spoke on behalf of her sisters, “We are glad we chose a campus where Christ walks side by side with each student” (Blodget et. al., 2007). Fiedler (2012) describes their tour to the north and east:

But the most memorable trip Neff and the Keys quads took was in May 1936. To encourage people to visit the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas that year, Neff and the four sisters traveled 5,000 miles across the country in a well-publicized goodwill tour. During the tour the Keys quads appeared on Fred Allen’s “Town Hall” national radio program in New York City and met Vice President John Garner in Washington, D.C.

This well-publicized tour attracted crowds of people wanting a chance to see the rare phenomenon of the quadruplets. Roberta wrote to her parents early on in the tour telling them that they were having the time of their lives (Blodget et. al., 2007). The quadruplets played and Neff spoke, and thousands of people heard about the Texas Centennial and, more importantly, Baylor (Blodget et. al., 2007). They traveled by train, planes, and cars and kept a very busy schedule, making appearances, meeting important figures, and even doing some sightseeing (Blodget et. al., 2007). The tour generated over 4,000 newspaper articles in 45 states, as well as Cuba and Canada (Blodget et. al., 2007).

Other Institutional Promotion

Awareness of Baylor also spread as extracurricular groups competed outside the city limits in various regional competitions. The Girls Choral club was “a leading organization among colleges of the southwest” (Facts and Views of Baylor). The debate squad had won 48 decisions in 60 contests. The Golden Wave Band was outstanding in the region, as well as the Boys Glee Club and the Baylor Little Theatre (Facts and Views of Baylor). They not only competed, but they competed well. The dedication of the students to excel in these organizations led to this positive publicity.

Alumni recognized the value of their time at Baylor, even promoting their beloved institution well into old age. According to Neff (1930) “every Baylor alumnus who has risen to any degree of prominence has reflected credit upon his alma mater.” They would “do good at home and around the world as long as time shall last” (Neff, 1930). As Baylor sent out missionaries and laymen alike, it sent forth ambassadors testifying Baylor’s value and impact throughout the world.

Conclusion

By 1940, Baylor boasted having 2554 students from 33 states and 7 countries (Baylor, 1940). With a 95% enrollment increase over the decade according to the Growth of Baylor Under the Presidency of Pat M. Neff, it was not a local school, but one known across the country and the world. The efforts so many had put into promoting the institution had paid off. The value of a Christian education was expounded, financial support increased, and the name of Baylor was widespread—efforts that would not have been successful without students showcasing their talents and volunteering their time and gifts. The hundreds of students involved in Field Days, the Keys quadruplets, the members of successful competitive organizations, and alumni played a crucial role in this promotion.

References

Baylor University (1940) [Promotional Pamphlet] Pat Neff Collection: Series 5, Subseries 2, Subseries 5 (Accession Box #58 Folder #6). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Blodgett, D., Blodgett, T., & Scott, D. L. (2007). The Land, the law, and the Lord: the life of Pat Neff : Governor of Texas, 1921-1925, President of Baylor University, 1932-1947. Austin, Tex.: Home Place Pub.

Directions for the Reception Committee (1936). [Handout]. Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #5 Folder #4) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Facts and Views of Baylor University [Promotional Pamphlet] Pat Neff Collection: Series 5, Subseries 2, Subseries 5 (Accession Box #58 Folder #18). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Field Day (1935). [Program] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #5 Folder #2) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Fiedler, R. (2012, April 26). Waco, Strange but True: Baylor’s double dose of quads. WacoTrib.com. Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://www.wacotrib.com.

“Growth of Baylor Under the Presidency of Pat M. Neff” [Report] Pat Neff Collection: Series 5, Subseries 2, Subseries 5 (Accession Box #64 Folder #6). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Karkabi, B. (2005, June 20). For Keys quads, rare birth was a blessing times 4. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://www.chron.com/life/article/For-Keys-quads-rare-birth-was-a-blessing-times-4-1502278.php

Keys, F. (1933, June 24) [Letter to Pat Neff] Pat Neff Collection, Series 4, Subseries 2 Subseries 3 (Accession Box #22 Folder #10) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Keys, R., Keys, M., Keys, M., Keys, L. (1933, July 10) [Letter to Pat Neff] Pat Neff Collection, Series 4, Subseries 2 Subseries 3 (Accession Box #22 Folder #10) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, P. Building Mansions in the Skies. (1930) [Promotional Pamphlet] Pat Neff Collection: Series 5, Subseries 2, Subseries 5 (Accession Box #58 Folder #6). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, P. (1933, February 27). [Letter to Keys Quads] Pat Neff Collection, Series 4, Subseries 2 Subseries 3 (Accession Box #22 Folder #10) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, P. (1933, June 1). [Letter to Flake Keys] Pat Neff Collection, Series 4, Subseries 2 Subseries 3 (Accession Box #22 Folder #10) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, P. An Epoch Making Chapel Service (1933, November 16) [Pamphlet] Pat Neff Collection: Series 5, Subseries 2, Subseries 5 (Accession Box #58 Folder #6). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, P. (1938, December 26). [Letter to Ralph Reid] Pat Neff Collection, Series 4, Subseries 8 Subseries 2 (Accession Box #62 Folder #4) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Russell, L. (1933, April 26). [Invitation to local seniors] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #4 Folder #12) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Russell, L. (1935). [Papers] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #4 Folder #12) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Russell, L. (1935). [Letter to Abbott High School] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #5 Folder #1) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Russell, L. (1936). [Notes] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #5 Folder #7) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Secretary Committee (1933, April 18). [Letter to Mrs. Cannon] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #4 Folder #12) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Secretary Committee (1933, April 19). [Letter to Dr. A. J. Armstrong] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #4 Folder #12) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

StoryCorps (2007). Roberta Keys Torn [Radio series episode]. In StoryCorps. Online: National Public Radio.

Thelin, J. R. (2011). A history of American higher education (2 ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Waco High School (1937). [Radio announcement] Lily Russell Collection, Series 7 (Accession Box #5 Folder #2) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.