Home to 64 seasons of Baylor football, Floyd Casey Stadium was demolished in 2016 (Ericksen, 2016). Dave Campbell—a Waco resident, longtime sports editor of the Tribune-Herald, and founder of Texas Football magazine—mourned the demolition of Floyd Casey with a kind of religious reverence:

[F]or a lot of us it will remain a stadium we will never forget, the site of unforgettable games and terrific football players…Now soon all of it will be just another victim of the wrecking ball, destined to be carted off to some unknown dumping ground. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust (Campbell, 2016).

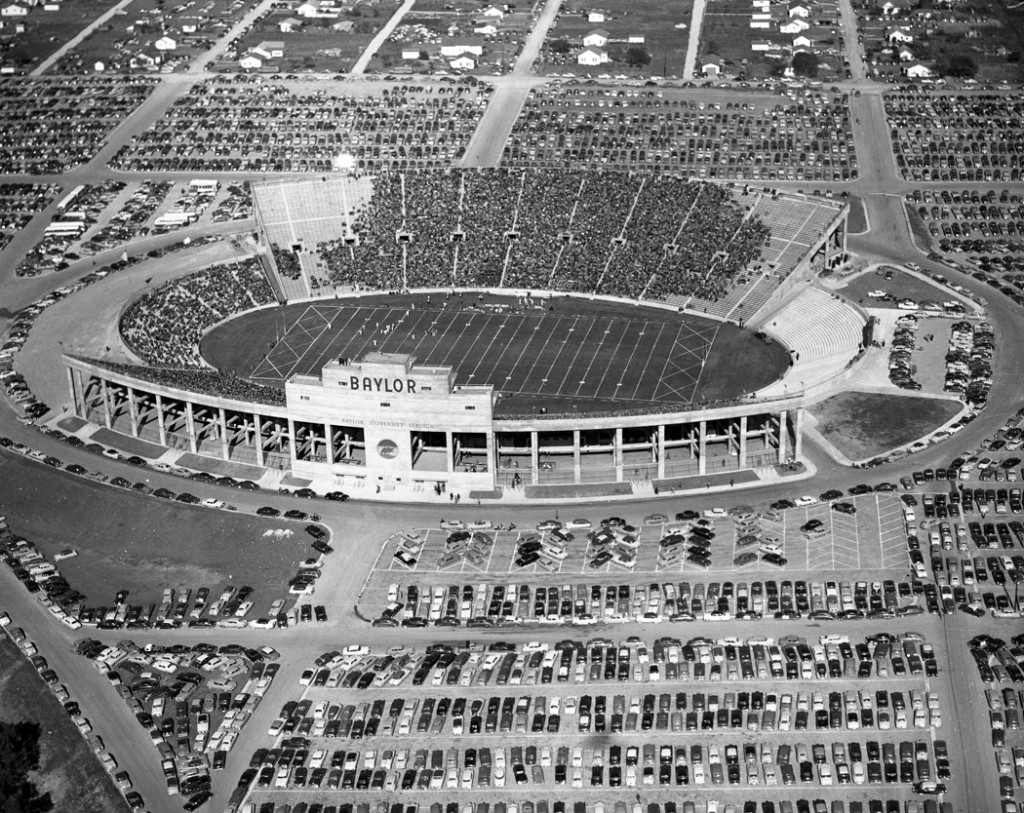

Floyd Casey’s reign came to an end this year, but what of its beginning? In the beginning, the stadium was not named Floyd Casey. The stadium was only renamed Floyd Casey in 1988 (Hunt, 2012). For 38 of its 64 seasons, “it was simply Baylor Stadium” (Campbell, 2016), and under that name, Baylor Stadium brought publicity, lawsuit, and modern television to Baylor, all in its first decade of existence.

The foibles and advances of the fundraising for, construction, and management of Baylor Stadium in the 1950s speak to the investment of Baylor, Waco, and Texas in Baylor Bear football. In the 1950’s alone, Baylor Stadium became both a boon and a burden to Baylor and its supporters across Texas. It was a source of publicity, a point of contention with the community of Waco, and a conduit to bring Baylor into the future of televised football.

Before Baylor Stadium: A legacy of sport in Waco.

As Floyd Casey preceded McLane, so Municipal Stadium preceded Floyd Casey—or rather Baylor Stadium (Simmons, 2012). By 1936, Baylor Football had outgrown Municipal’s 20,000 seats, and new stadium talks began (Simmons, 2012). Then, as now, Baylor valued its legacy as the one of the oldest universities in Texas and prioritized historical significance when considering where to build Baylor Stadium—subsequently renamed “Floyd Casey Stadium”.

Baylor had kept historical legacy in mind when building Municipal Stadium, which stood at the old Texas Cotton Palace grounds (Simmons, 2012). The Texas Cotton Palace was a nineteenth century annual, month-long agricultural exhibition featuring Waco’s economic fares—e.g. cotton trade—and entertainment amenities—e.g. a racetrack and a Ferris wheel (Stingley, 2016). The Cotton Palace had served as the entertainment and sports center of Waco. After it, Municipal Stadium served the same purpose on the same plot of land. In the 1940s, Baylor wanted to tear down Municipal Stadium and rebuild Baylor Stadium on the same grounds to carry on the tradition of both Municipal and The Cotton Palace before it (Simmons, 2012).

Instead, a geological fault and insufficient parking space trumped legacy (Simmons, 2012). Despite the ongoing entertainment history attached to the land beneath Municipal Stadium, Baylor purchased a 100-acre plot for a new stadium that would hold up to 49,000 spectators, more than doubling Municipal’s maximum capacity (Simmons, 2012).

Perhaps it is this legacy of entertainment and sport that first endeared the Baylor community to Baylor Stadium and would justify the sacrifices and struggles that were to come. The Cotton Palace and Municipal Stadium had laid the groundwork of loyalty from which Baylor Stadium would benefit.

The Baylor Stadium Campaign: The eyes of Texas are upon Baylor.

The purchase of land for the new stadium was announced in The Waco News-Tribune in February of 1949, and in March of that year, the Baylor Stadium Corporation—the managing entity of the Stadium’s construction and ongoing operations—was incorporated (Baylor Stadium Corporation, 1955). That summer, the “Baylor Stadium drive [began]…and by fall had spread to 120 counties throughout the state“ (Baylor University, 1949, p. 1). The campaign set high aspirations: cover the estimated cost of $1,500,000.00 and ensure the completion of construction by the Bears’ first home game in 1950 (Baylor University, 1949). This gave the Baylor Stadium Campaign and the Swigert Construction Company less than a year to raise the funds and build the stadium.

The pressure to complete fundraising and construction mounted as the campaign’s publicity drew focus from across Texas.

Once the decision was made, both the city and Baylor went whole hog. It seemed people were selling those bonds from every venue to help pay for the new stadium. And in what was perhaps the most memorable event of all, Houston oilman Glenn McCarthy, also builder of Houston’s big new hotel “the Shamrock” and man of many headlines, came to Waco to be the main attraction in a big Waco downtown parade to publicize and push stadium bond sales (Campbell, 2016).

In November of 1949, The Daily Lariat reported, “’The eyes of Texas’ will all be focused on Baylor University December 2nd. To celebrate the anticipated Baylor Stadium drive victory, Governor Allan Shivers Thursday proclaimed December 2nd as ‘Baylor Day’ throughout the whole state” (Baylor University, 1949, p. 1). Baylor had very publicly promised Waco and donors across Texas a new stadium by the 1950 season.

As of January 1, 1950, the drive still lacked nearly $500,000.00 (Taylor, 1950). By June, a mere three months before the season opener, the contractor raced to complete 41,000 seats, surrounding streets, parking lots, and various other facilities (Wood, 1954). In the end, the stadium was left incomplete for its first season (Financial Statement Calendar Year 1955, 1955). More than that, final costs exceeded estimated costs by $168,460.15. Despite the difficulties, the stadium was complete enough to begin play there in the 1950 season (Financial Statement Calendar Year 1955, 1955).

The dedication ceremony took place at Baylor’s first home game against the University of Houston Cougars on September 30, 1950 (Baldwin, 1950). Despite occurring in an incomplete stadium, the ceremony’s fanfare matched the hype of the campaign: Conally Air Force Base sent “planes to do a flyover…while the University of Houston played the national anthem and the Baylor Air Force ROTC color guard raised the colors” (Simmons, 2012). Revelry abounded, and the Bears brought home a 34-7 win to christen the new stadium.

The Baylor Stadium Campaign, ensuing speedy construction, and grand opening ceremonies speak to the degree of Baylor’s investment in Baylor Stadium. Baylor University had incorporated a new entity, mounted a statewide fundraiser, and been so committed to meeting the 1950 deadline that they were willing to host an entire season in an incomplete stadium. Baylor University was determined to make Baylor Stadium a reality, and they rallied the entire state of Texas to achieve that end.

Baylor Stadium Corporation: An operation of goodwill and strong winds.

By 1951, with construction and the first season behind them, Baylor Stadium Corporation would face three tasks in the first decade: first, pay-off the 1.5 million dollar debt incurred for construction; second, manage the stadium’s considerable income; and, third oversee renovations to ensure the relevancy of Baylor’s new football facilities.

Baylor Stadium Corporation’s ongoing task was to manage stadium facilities and corresponding revenue. The Baylor Stadium Corporation had two primary sources of income. The first source of income came from revenues generated by the facility itself—e.g. parking fees and ticket sales. The second source of income was funded directly by the Baylor University.

Baylor Stadium Corporation was contractually owed the greater of “either the net receipts or 15 percent of gross receipts” of the athletic department’s total income (Wood, 1955, p. 1). In essence, regardless of success or financial viability, the Stadium Corporation was guaranteed a portion—the greater of two potential portions—of the athletic department’s earnings. In 1950, the first year Baylor Stadium was in service, the stadium did not boost athletic department earnings enough to justify that promise. In fact, the athletic department fell sufficiently short that “Baylor had to supplement… [those] earning[s] to meet the minimum of 15 per cent [sic]” (Wood, 1955, p. 1).

Baylor’s willingness to promise the greater portion of a fluctuating income—despite potential and actual shortfalls—to the Stadium Corporation demonstrates the University’s commitment to Baylor Stadium. This commitment, coupled with the high-profile fundraising campaign and the University’s strict adherence to the opening date speak to the University’s stake in Baylor Stadium. Baylor made early bets on the anticipated returns of the stadium. Whatever returns would come for the University, however, the Stadium Corporation’s first obligation was to the financial and managerial demands and liabilities of the stadium itself. Pragmatically speaking, Baylor Stadium would not run itself.

Preparation for the ongoing maintenance of Baylor Stadium began during construction. Two houses on Dutton Avenue were moved to accommodate a wider entrance to Baylor Stadium (Taylor, 1950). One was “moved to another location on the stadium grounds” to serve as an eventual home for Baylor Stadium’s caretaker (Taylor, 1950, p. 1). The Stadium Corporation supervised the caretaker and directed general operations. After a high school playoff game, Roy Wolf, chair of The Baylor Stadium Corporation for most of the 1950s, joked about the thrift with which the Stadium Corporation managed this task: “[Wolf] said drily, ‘I waited a day or two [after the playoff game] hoping a high wind would blow all the trash to one end of the stadium and make the cleaning up easy. Sure, I save $100 every now and then with a high wind’ (Wood, 1952, p. 12).

In addition to the obligation of running the stadium, the Corporation had to repay the debt incurred by the Baylor Stadium Campaign. Construction “was financed principally by an authorized bond issue of one and one-half million dollars payable over a period of 30 years at an annual interest rate of 3 per cent [sic]” (Financial Statement Calendar Year 1955, 1955). Some bond options came with choice seating and others came with tuition remission. In total, Baylor Stadium Corporation had to repay $1,348,000.00 by 1980 when the bonds retired.

After the 1950 subsidized season, the Baylor Stadium Corporation made its first profit and began to retire bonds early. Bonds retired prior to 1980 would provide bondholders with only a percentage of their original investment. The longer a bond had to mature, the more interest it accrued. The Stadium Corporation had a vested interest in retiring bonds early to decrease their outstanding liability as well as limit interest accrual.

In typical financial investment circumstances, bondholders have opposing interest from the issuers of the bonds. However, the Stadium Corporation presumed that the Baylor Stadium bond issue did not fit typical financial investment circumstances. They knew some bondholders would retain bonds for their tuition or investment value (Wood, 1955). However, many bondholders purchased bonds out of loyalty to Baylor rather than for financial gain. Thus, the Stadium Corporation began to systematically retire bonds early.

The Stadium Corporation used revenues to create a reserve fund for ongoing redemption of bonds and to retire bonds early from amenable bondholders. Some years a general notice was sent out to bondholders at large requesting early redemption (Wood, 1955). Other years, the Stadium Corporation targeted specific bondholders. For example, in 1952, the Stadium Corporation used 1951 profits to redeem only bonds valued at $51,200 (Wood, 1952).

In either case, Baylor Stadium Corporation counted on bondholders’ willingness to suffer financial loss for Baylor’s sake. Bondholders were willing “to tender their bonds for a price less than par value (purchase price)… in order to benefit Baylor Stadium Corporation and Baylor University” (Wood, 1955, p. 1).

Bondholders were willing to retire bonds at a loss—e.g. in 1954 the Stadium Corporation redeemed bonds at an average discount of 89.424 cents on the dollar (Wood, 1954)—out of a sense of loyalty to Baylor University. In turn, Baylor University fronted the land purchase, mounted a high profile campaign, and dedicated the greater portion of a fluctuating income to the Stadium Corporation because of the anticipated returns of Baylor Stadium.

In short, Baylor Stadium Corporation’s obligations were to run and repay the debts of Baylor Stadium. The running of the stadium is what benefited the Baylor community at large, hosting both Baylor games and playoffs for community teams. This everyday operation is what the stadium had been built for: to house the sporting events of the community. However, in order to achieve that task, Baylor University and Baylor Stadium bondholders had to take a financial hit. It was a price they willingly paid for the other benefits of Baylor Stadium.

Returns on Baylor Stadium: Publicity, lawsuits, and televised football.

On the most basic level, Baylor Stadium served as a source of publicity for Baylor. At its very inception, the Baylor Stadium Campaign drew attention from across the state. After construction, the stadium continued to draw focus. In 1951, Baylor Stadium hosted the Orange Bowl generating the highest revenues from 1950-1956 and increasing Baylor’s notoriety (Wood, 1955). By 1952, the Stadium Corporation was financially stable enough to donate facility use to high schools for playoff games, free of charge (Wood, 1952). The Stadium Corporation also donated facility use to local clubs. The Waco Quarterback Club used Baylor Stadium for spring practice at no charge but operating expenses—e.g. marking the field, cleaning the stands, etc. (Wood, 1954). To high schools and quarterback clubs alike, Baylor Stadium provided a needed service and expanded the Baylor brand as one of goodwill and community participation.

Not all press, however, was good press for Baylor Stadium. In February of 1955, Wilbur F. Crawford, a local businessman, contacted the Baylor Stadium Corporation about the desire to open a street adjacent to Baylor Stadium (Letter from W.F. Crawford, 1955). This street would allow for easier access to parking and to the stadium at large. In his letter and the accompanying proposal, Crawford offered to fund the project and only needed the Baylor Stadium Corporation to donate the land, which they did.

In the aftermath of this seemingly innocuous arrangement, a coalition of residents who lived along the proposed street and the Missouri-Kansas and Texas Railroad—Katy Railroad—filed a temporary injunction to stall construction (Wood, 1955). Katy Railroad and the residents claimed that the new street would create an unsafe intersection across the railroad tracks and was only being built to benefit Baylor, not the Waco Community (Wood, 1955). However, the Waco community at large did not agree with this sect of the population. Waco citizenry backed Baylor and Crawford’s street project:

The city of Waco gained unexpected backing…when it received a petition signed by a score or more of South Waco and Beverly Hills citizens protesting the action of the Katy in holding up the opening of the new street…the petition urged the city to take whatever steps were necessary to obtain the right-of-way needed across the Katy tracks and offered the individual services of the petition signers if they could help in any way (1955, p. 1).

The City of Waco won the case, and street construction continued apace. The goodwill of the bondholders towards Baylor Stadium was shared by the local Waco community, if not local residents.

The street was not the only construction project that took place in the first decade of Waco Stadium. By 1955, it became apparent that technology and football media coverage was advancing beyond what the Baylor Stadium facilities could accommodate. Despite its newness, Baylor Stadium had become outdated. Baylor Stadium Corporation’s finance committee for 1955-1956 argued for the need to add lighting. As of 1955, Baylor became the only remaining college in the Southwestern Conference without stadium lighting (Finance Committee, 1955-1956).

At that time, regional TV stations covered a single college football game each week, and so all games took place at the same time during the day (Finance Committee, 1955-1956). However, the Big Ten and Pacific Coast Conferences began to lobby for broader coverage of multiple football games throughout the weekend (Finance Committee, 1955-1956). Lights in football stadiums allowed for a larger time frame in which games could take place. This increased the window for TV broadcast (Finance Committee, 1955-1956).

Installing lights to Baylor Stadium would open up possible broadcasting slots for Baylor games. “Baylor would be placed in an advantageous position if they were able to switch their home games from day to night or vice-versa in order to avoid television competition” (Finance Committee, 1955-1956, p. 3). Lights would also entice northern teams who might otherwise be put off by the heat of a Texas day game (Finance Committee, 1955-1956). Installation of 32 lights to stadium poles and the parking lot would cost the Baylor Stadium Corporation between $60-$75,000.00 (Finance Committee, 1955-1956). The stadium was only five years old, and unless the Corporation managed to retire all bonds early, it would still be leveraged until 1980. Yet to be paid for, Baylor Stadium was already on its way to irrelevancy.

Once again, Baylor and its community backed Baylor Stadium. Baylor Stadium no longer benefited from an inherited legacy alone. Baylor Stadium had earned loyalty in its own right, as the home of quarterback clubs, high school play-off games, and as the source of publicity for Baylor. These early returns, though not always financial, reinforced Baylor’s belief in the value of Baylor Stadium. Waco’s defense of Baylor in the face of litigation speaks to the fact that this mentality was not limited to the institution. The shared belief in Baylor Stadium would help to justify its further expansion and renovations, a belief that was quickly put to test with the need for early renovations.

Conclusion: Blind bets on loyalty.

On this side of 1956, investment in a college football stadium seems commonplace. But when Baylor mounted the audacious stadium campaign, fought for a new street, and even installed stadium lights, they could not have known that college football would come to own a day of the week on college campuses across the nation. They had no notion of weekly, nationally broadcast college football games, as dependable as any other televised program. Indeed, by virtue of the early renovations, they did not predict such a windfall of technology and media coverage. Nonetheless, Baylor, the Baylor Stadium Corporation, Waco, and Texas bore the cost of construction, management, and renovation in the span of a decade—this in an era of one televised game a week.

Though unknown then, Baylor Stadium would eventually bring Baylor University into the televised age and with it, expand the brand of the institution. At its inception, however, Baylor Stadium was a bet that Baylor made on the loyalty of the Baylor community, Waco, and Texas. That loyalty manifested in the support of stadium lights, the battle over street litigation, a subsidized budget that first year of existence, a speedy construction, and a high-profile campaign. This loyalty was passed from The Cotton Palace to Municipal Stadium; from Municipal to Baylor Stadium; to Baylor Stadium again under the new name Floyd Casey Stadium; and from Floyd Casey now to McLane Stadium.

In 1950, the Baylor Bears won their first game in Baylor Stadium. In 2013, the Bears won their last game and became Big 12 Champions in the same facility (Campbell, 2016). After seventy years, few people remember the willing loss of Baylor Stadium bondholders, the rallying of Waco behind Crawford’s new street, or Roy Wolfe’s prayers for a gusty wind. They remember Floyd Casey Stadium, a name that did not exist when it all began. Was Baylor Stadium worth the investment? Was Baylor justified to replace Municipal Stadium with its grander successor? After all, now Baylor Stadium has a grander successor of its own. Perhaps Baylor’s ongoing and growing investment in football stadiums is all the answer that is needed. Whether or not the numbers add up, Baylor Nation believes in Baylor Football.

References

Baldwin, Frank (Ed.) (1950, July 1). Baylor stadium ceremonies set. The Waco News-Tribune. p. 9. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/image/47931515/?terms=stadium%2Bcorporation.

Baylor University (1949, November 9). Shivers proclaims December 2 as statewide ‘baylor day’. The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/utils/getfile/collection/lariat/id/23907/filename/26700.pdf.

Campbell, D. (2016, April 21). Dave campbell: stories come alive as floyd casey crumbles. WacoTrib.com Retrieved from http://www.wacotrib.com/sports/baylor/football/dave-campbell-stories-come-alive-as-floyd-casey-stadium-crumbles/article_3c1f9ba7-b5b7-5573-9ce7-72c3bb4c2a9b.html.

Ericksen, P. (2016, February 1). Demolition of floyd casey stadium underway. WacoTrib.com. Retrieved from http://www.wacotrib.com/news/higher_education/demolition-of-floyd-casey-stadium-underway/article_badef8e0-c6ff-5e18-aabd-556be2cc0e9b.html

Ericksen, P. (2016, February 1). Demolition of Floyd casey stadium underway. WacoTrib.com. Retrieved from http://www.wacotrib.com/news/higher_education/demolition-of-floyd-casey-stadium-underway/article_badef8e0-c6ff-5e18-aabd-556be2cc0e9b.html.

Finance Committee: Baylor Stadium Corporation (1955-1956) BU Records: Office of the President, Chancellor and President Emeritus (W.R. White) #BU/142. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Financial Statement Calendar Year 1955: Baylor Stadium Corporation (1955). BU Records: Office of the President, Chancellor and President Emeritus (W.R. White) #BU/142. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Letter from W.F. Crawford: Baylor Stadium Corporation (1955, February 7). BU Records: Office of the President, Chancellor and President Emeritus (W.R. White) #BU/142. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Simmons, B. M. (2012, September 14). A fittin’ home for the fightin’ Baylor bears: The 1949-1950 baylor stadium campaign. The Texas Collection. Retrieved from https://blogs.baylor.edu/texascollection/2012/09/14/a-fittin-home-for-the-fightin-baylor-bears-the-1949-1950-baylor-stadium-campaign/.

Stingley, J. (2016). The Texas Cotton Palace. Waco History. Retrieved from http://www.wacohistory.org/items/show/15.

Taylor, E. (1950, January 20). Stadium progress is good despite weather conditions. The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/23753/rec/172.

Wood, Sam (Ed.). (1952, February 12). Nash is named to head bu stadium group. The Waco Tribune-Herald. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/image/43650212/.

Wood, Sam (Ed.). (1952, December 24). Temple, breck divide $26,970. The Waco News-Tribune. p. 12. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/image/48027647/?terms=stadium%2Bcorporation.

Wood, Sam (Ed.). (1954, February 7). Stadium heads meet monday. The Waco News-Tribune. p. 20. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/image/43635364/?terms=stadium%2Bcorporation.

Wood, Sam (Ed.). (1954, February 9). Stadium group names officers. The Waco News-Tribune. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/image/43637748.

Wood, Sam (Ed.). (1955, January 21). Bear athletics net $101,261 in ’54 for payment on stadium. The Waco News-Tribune. p. 1. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/image/47938108/?terms=stadium%2Bcorporation.

Wood, Sam (Ed.). (1955, September 1). Street injunction case to be heard on Tuesday. The Waco News-Tribune. p. 1. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/image/49100194/?terms=stadium%2Bcorporation.