By Kristin Koch

Higher education in America was founded on the liberal arts, and its influence remained throughout the 1950s. The emphasis on its importance for all college students, however, dwindled as new areas of study emerged. The post-World War II society provided a golden age for higher education (Thelin, 2011). Access was granted to the masses, including veterans, programs were becoming more academically rigorous, enrollments were skyrocketing, and new types of education were developing. These dynamic changes affected universities’ course offerings and curricular structure in order to cultivate students into well-rounded, skillful, and employable citizens. In light of the post-World War II environment, society viewed higher education as an opportunity to gain vocational skills in addition to intellectual virtues, which required specialized fields of study to be added to the existing liberal arts education at Baylor in the 1950s.

Evolution of Specialization

The liberal arts education was the foundation of higher education because it created an environment of learning for its own sake, which made education worthwhile regardless of vocational goals (Hutchins, 1936). The pursuit of knowledge for its own sake unified students through a common curriculum and created a foundation that prepared them for post-graduate life where they could be successful in any job position, once properly apprenticed. Hutchins (1936) argues that these vocational experiences should be left to life situations, graduate studies, or professional programs rather than undergraduate education because the goal of higher education was to pursue intellectual virtues.

After World War II, enrollment numbers grew and new student demographics were seen on campuses including older students, working men and women, and veterans. Many of these types of students were attending college with the goal of obtaining a job in order to make more money to support their families (Thelin, 2011), which contributed to the appeal of specialization. The federal government was trying to move the economy from a time of war to a time of peace, which included finding a solution for “avert civil strife of disgruntled military veterans who arrived home without jobs or good prospects” (Thelin, 2011; p. 262). The GI Bill increased enrollment by making higher education affordable for veterans, and universities marketed education as a way to develop character and gain practical skills for the workforce.

As more students went to college, there was an increased need to graduate them faster in order to open admissions for new students (Thelin, 2011). This new objective increased the need for specialized majors that quickly trained students rather than broadly educating them through a traditional liberal arts curriculum, which made the notion of a “multiversity” (Kerr, 1963) very appealing. Kerr (1963) argues that the multiversity can better accommodate different groups of students, including “the ‘academic’ of the serious students; [and] the ‘vocational’ of the students seeking training for specific jobs…These subcultures are not mutually exclusive, and some of the fascinating pageantry of the multiversity is found in their interaction one on another” (p. 42). By offering more programs and options for students, the multiversity meets the needs of more students by offering both liberal arts and specialized courses.

The multiversity offered students a wider range of choices within their education, allowed for more creativity, created new knowledge to be explored for social and economic growth, and was financially beneficial to the university as it accommodated larger numbers of students with diverse interests (Kerr, 1963). As postsecondary education increased in popularity and societal needs changed, specialized curriculum became a necessary addition to the pre-existing liberal arts education.

Specialization at Baylor University

Baylor University in Waco, Texas experienced curriculum transformations similar to the rest of the country in the post-war climate. In the 1950s, additional departments were added to various colleges to either enhance the liberal arts experience or provide a new, vocational-oriented education. Baylor supplemented the liberal arts with specialized course rather than replacing them because the university valued the underlying benefits of the liberal arts education and the pursuit of intellectual virtues.

In the 1950s, Baylor had six colleges: College of Arts and Sciences, School of Business, School of Law, School of Music, School of Nursing, and the Graduate School. In 1957, the School of Business became “completely autonomous with respect to its internal affairs. It is hoped that arrangements can be completed whereby the Schools of Music and Nursing can achieve this status shortly” (Smith, 1957; p. 6-7). These vocation-oriented colleges became their own entities in this era because they were gaining support from administrators, donors, faculty, and students.

President W. R. White defended the need for specialization by saying “[w]e certainly need some specialization that we might have a thrust and witness in the leadership professions that are most influential. We refer to the ministry, teaching, law, business, medicine, nursing, and dentistry” (White, 1960b). The president of Baylor University in the 1950s identified specialized education as a necessary component of effective leadership when, historically, the liberal arts education was the curriculum taught to develop leaders. Vocational curriculum was added to the training deemed necessary to prepare students for society.

Vocational training became a sought-after option for many college students, and universities worried that the unifying aspect of the liberal arts education would be lost. In 1957, Baylor saw this need for commonality among students. The Dean of Instruction at the time thought “too many of our students begin specialization to the neglect of their basic work” (Smith, 1957; p. 12). This “basic work” historically occurred over a four-year liberal arts education to develop intellectual virtues and create unity among students. As specialization appeared on college campuses, students spent less time studying the foundational subjects. Liberal arts were only recommended to students for one to two semesters in the 1950s before they chose their college and later their major (Smith, 1957). Students pursuing vocational training were spending less time in liberal arts courses but were pursuing depth in their fields of study.

Despite the decreasing prominence of the liberal arts, its spirit continued to be part of Baylor’s educational emphasis. President W. R. White wrote, “Baylor has always emphasized a balanced education program – a blueprint designed to produce a balanced and self-reliant people. Baylor has aimed not alone for an educated mind, but for an educated conscience” (White, 1960a). Even amidst the increase in specialized curriculum’s popularity, Baylor strove to keep the pursuit of intellectual virtues intact. President White also spoke about creating a “balanced Baylor” that provided opportunities for learning in the liberal arts as well as in many specialized and professional fields (White, 1950). Baylor hoped to incorporate the societal demands for vocational training into their pre-existing liberal arts institution.

The purpose of education at Baylor in the 1950s was “[f]irst, to develop the mind’s capacity to think. Second, to get one to make an independent life. Third, to enhance the individual’s usefulness to his country and society” (White). W. R. White’s goals seemed to align with the original goals of a liberal arts education, but they were interpreted differently. Many people in society in the 1950s interpreted the ability to think as having specific skill sets, not thinking critically about overarching thematic concepts. They understood an independent life as being financially stable rather than physically independent from their parents. Society also viewed a person’s “usefulness to his country” (White) as having a job and contributing to the economy, not necessarily being an elite leader, as was the case in previous eras. This shift in society’s understanding of these goals required specialization to be added to the existing liberal arts education at Baylor in the 1950s.

Specific Effects of Specialization at Baylor University in the 1950s

At the beginning of the 1950s, the College of Arts and Sciences consisted of 60% of all students enrolled at Baylor University (Baylor University, 1949), but by the late-1950s, it decreased to 57% (White, 1957a). Although the College of Arts and Sciences enrollment decreased, the liberal arts still consisted of the majority of degrees awarded to students: 52% of granted degrees in 1959 were Bachelor of Arts degrees (Baylor University, 1959).

The School of Business, on the other hand, had an enrollment of 16.78% in the early 1950s (White, 1952) and increased to 22% by the end of the decade (Baylor University, 1959). As more students attended Baylor for vocational reasons, the appeal of employable business degrees was growing and quickly gaining on the liberal arts.

While the liberal arts were still alive and well at Baylor in the 1950s, specialized fields received increased resources and attention as they grew in popularity. Salaries in 1957 reflected the increased demand and perceived value of specialized fields of study. The Dean of Instruction, George Smith, even pointed out that the “School of Business, Chemistry, and Physics faculties are reasonably well paid, and considerably better paid than the remainder of our teachers…our salaries in Mathematics must be made much more attractive” (Smith, 1957; p. 8). The faculty of vocational and popular courses was receiving larger salaries than the liberal arts professors.

Additionally, building facilities for specialized fields of study were prioritized over those for the liberal arts because they were seen as critical to Baylor’s future. The Dean of Instruction believed that “an adequate Science Building is our most pressing need” (Smith, 1957; p. 9) in 1957 because the existing facilities were inadequate for the future growth in the sciences. The Dean also put priority on building a business building for that growing, specialized field. Mr. and Mrs. Earl Hankamer donated $500,000 to “make this the outstanding school of business in the Southwest” (White, 1959; p. 4). Resources and administrative attention were directed at specialized curriculum in the 1950s largely because of the demand in those areas among Baylor students.

Veteran Enrollment

The effects of the GI bill on enrollments, which then influenced curriculum, were seen throughout this era. There were approximately 40 veterans enrolled at Baylor University in the 1944-1945 academic year (about 2% of the student population), but the next year their enrollment spiked to 1128, about 36% of the student population, followed by 53% from 1946-1947 (Baylor University, 1954). By the start of the 1950s, veteran enrollment had decreased to about 40%, but they continued to hold at least 20% of total enrollment (see Table 1) throughout the decade (Baylor University, 1954).

The reduction in veterans on campuses from the late 1940s to the early 1950s could be explained by several different circumstantial factors. First, in 1951 President W. R. White noted that “the falling off of the number of G. I.’s and the drafting of the other boys into the service” (White, 1951; p. 1) attributed to decreased student enrollment and faculty positions. Second, in the late 1950s, the Dean of Instruction stated that “the slightly stiffer admissions policy denied admissions to several” and they could not admit more students until they increased the faculty size (Smith, 1957; p. 4). Despite the slight decline explained by these environmental factors, the veteran population still made up at least 20% of the student population and was a group of students with unique needs to be met.

At the beginning of the 1950s, veterans consisted of about 56% of the College of Arts and Sciences, 86% of the School of Business, and 94% of the School of Law (Baylor University, 1949). Veterans seemed to be drawn more to the majors that lead directly into employment, which is consistent with the trends of the era. Veterans seemed to be drawn towards employable majors because they tended to be older students who had families to support. Veterans also had to put their career goals aside when they went to war; many of them hoped to get through school quickly to get back on track with their goals. Additionally, veterans had hands-on experience during wartime so they tended to prefer practical majors and skills.

Summer Sessions

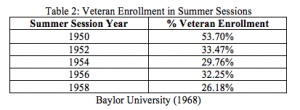

Summer sessions were becoming more popular at Baylor University during this era, and veterans were using it to their advantage. In the 1944-1945 and 1945-1946 academic years, there were more veterans enrolled in summer courses than veterans enrolled in the regular-year courses (Baylor University, 1954). During World War II, veterans consisted of only 7% of summer session enrollments, but the year immediately following the war, 69% of the summer enrollment consisted of veterans because of the GI Bill. By the 1950s, this percentage dropped to 25-50% (Baylor University, 1954): see Table 2. This drop in veteran enrollment in summer sessions may be due to the onset of the Cold War as students were drawn away from their education to focus on war-time needs.

Dean Monroe Carroll stated that the summer sessions were “arranged to accommodate many groups who are affected by the nation’s mobilization and military preparedness program” (Baylor University, 1951 May). In order to accommodate more students, Baylor adapted to the wartime environment by creating these programs that allowed more people to receive an education. Also, the “veterans who are rushing to complete their college work also have been given primary consideration…Three hundred thirty courses in 37 departments are scheduled for the summer term” (Baylor University, 1951 May). Summer sessions allowed veterans and other students to join the military or workforce faster by complete their degrees quicker. Additionally, students had the option of enrolling in an accelerated program where they were “able to graduate in three rather than the normal four years” (Baylor University, 1951 May). Society in the 1950s encouraged faster completion of a college degree than in previous years because of the emphasis on finding a job or joining the military as soon as possible. Baylor offered access to enormous groups of people through summer programs that offered an accelerated and broad curriculum that satisfied any specialized or liberal arts degree.

As more students were attending college, Baylor hoped to accommodate more diverse populations who hoped to graduate quickly. Historically, colleges did not put much emphasis on students completing degrees quickly, but as enrollments skyrocketed, they required students to go through the undergraduate process faster in order to free up admissions for new students. To help this process, President W. R. White started marketing the summer sessions to entering Baylor freshmen. He described it as “an extraordinary opportunity for a good study. Life is not so complicated and the activities are at a minimum. Real progress can be more easily made than at the regular session as a rule” (White, 1961). Summer sessions, as accessories to specialization, were seen as a catalyst for student success at the university, so students were encouraged to participate and speed up their collegiate experience.

The Evening Division

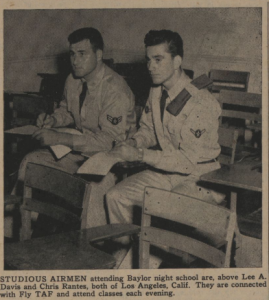

Evening classes were also increasingly popular throughout the decade in order to “give every interested person in this area a chance to further his education in any field he chooses” (Baylor University, 1952b). In 1955, there were 445 students enrolled in the Evening Division, and by 1959 the number increased to 779 (Baylor University, 1960). This increase in demand for night classes caused the curriculum to expand in order to accommodate more groups of students with different vocational interests.

The Evening Division was a program that Baylor used to set more students up for success after graduation. Classes at night offered full-time workers a chance to further their education affordably. It also allowed students with children to take courses. Mr. and Mrs. Benson, who had two children, both attended night classes twice a week under the GI bill (Baylor University, 1951 March). Mr. and Mrs. Benson’s story, as shown in Figure 1, discussed how easy it was for two veteran parents to attend Baylor and raise a family all without hiring babysitter (Baylor University, 1951 March).

In addition to families and veterans, students pursuing advanced degrees were also taking night classes if they were occupied during the day with research or teaching (Baylor University, 1952a). The Evening Division was a form of curricular specialization that benefitted new populations of people that would otherwise not have the time to obtain a degree.

Conclusion

As veteran and general enrollment increased at Baylor University in the 1950s, specialization was balanced with the existing liberal arts curriculum. Specialized areas of study, such as business and sciences, grew in popularity and size, especially among veterans or students who sought practical, employable degrees. Summer sessions and night classes offered an option for students to complete degrees quickly in order to enter the workforce earlier, which appealed to many of the non-traditional students that enrolled at Baylor in large quantities during the 1950s.

Higher education moved towards specialization in the 1950s to fit society’s goals for education as men came home from war and sought out jobs to support their families. The objective of college was no longer to simply develop students into productive citizens; the goal was to create skillful, employable, and intellectually virtuous citizens who could contribute to society by finding a job upon graduation. Higher education met the needs of students and society by balancing specialized fields of study with a liberal arts education to set increasingly diverse groups of students up for success.

References

Baylor University. (1949). Baylor university bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor University. (1950). Classification of students [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Attendance Reports 1949-50, Box #1). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Baylor University. (1951). Classification of students [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Attendance Reports 1951, Box #1). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Baylor University. (1951, March 6). Mr. and mrs. benson prove anybody can go to college. The Baylor Lariat, Vol. 52, No. 83, pp. 1. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/25211/rec/32

Baylor University. (1951, May 4). BU summer session slated to be strongest on record. The Baylor Lariat, Vol. 52, No. 116, pp. 2. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/24503/rec/65

Baylor University. (1952a, June 13). Air force personnel take time to study in evening classes. The Baylor Lariat, Vol. 53, No. 107, pp. 1. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/25869/rec/74

Baylor University. (1952b, June 13). Moore resigns as director of night school. The Baylor Lariat, Vol. 53, No. 107, pp. 1. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/25869/rec/74

Baylor University. (1954). Report of a survey of baylor university [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Report of a Survey of Baylor University 1954, Box #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Baylor University. (1959). Degrees issued by baylor university, 1958-1959 [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Degrees 58-59, Box #6). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Baylor University. (1960, April 13). Report of baylor university evening division course enrollment [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Report of the Evening Division, Box #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Baylor University. (1968). Report of the registrar [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Report of the Registrar 1967-68, Box #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Hutchins, R. M. (1936). The higher learning in america. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kerr C. (1963). The uses of the university. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smith, G. M. (1957, October 18). Report of the dean of instruction [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Report of the Dean of Instruction, Box #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Thelin, J. R. (2011). A history of american higher education (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

White, W. R. Education and social responsibility [Speech]. W. R. White Collection, Personal Papers (Folder Education and Social Responsibility, Box #3). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1950). A balanced baylor [Speech]. W. R. White Collection, Personal Papers (Folder Speeches – Dr. White 50-51, Box #4). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1951, February 15). [Letter to Chuck Devereaux]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Faculty 51, Box #6). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1952). Summary in brief [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Registrar 52, Box #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1957a). Classification of students [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Registration 56-57, Box #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1957b). Combined summary in brief [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Registration 57, Box #8). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1959). Report the president [Report]. W. R. White Collection, Baylor University Records (Folder Report of the President, Box #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1960a). The baylor challenge [Speech]. W. R. White Collection, Personal Papers (Folder Baylor’s New Day, Box #3). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1960b). The dilemma of christian education [Speech]. W. R. White Collection, Personal Papers (Folder The Dilemma of Christian Education, Box #3). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1961, July 7). Challenge to baylor freshmen [Letter]. W. R. White Collection, Personal Papers (Folder Speeches – Misc, Box #4). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX