The Student Personnel Bureau

Colleges have always had students; they have been the foundation for a collegiate education since the beginning. However, colleges have not always treated students the same way nor has there ever been a clear answer to the question, “What is an educated person?”

In the beginning, at the establishment of the colonial colleges in the United States, colleges focused on the development of proper, Christian gentleman, with most professors being clergy members (Thelin, 2011). As time passed and colleges grew, the shift of faculty from a student focus to a focus on their field of study meant that students would rely “on their own solutions” (Alleman & Finnegan, 2009, p. 14). This self-reliance would continue until the early-1920s, when Walter Dill Scott began applying the methods that he had originally applied and refined in U.S. Army recruitment, to American higher education (Biddix & Schwartz, 2012). Slowly but surely, student personnel work was on the rise.

Baylor was a pioneer in Texas for student personnel work, as the first college in Texas to create a student personnel bureau in 1935 (Reaves, 1935, September 17). However, the introduction of this bureau was a departure from the tone that then president Pat M. Neff had set a mere two years before.

Changing of the Guard

In the 1920s, the president of Baylor University, Samuel P. Brooks, put a large emphasis on the student’s life in the classroom. Eugene W. Baker (1987), former Baylor historian, describes this emphasis in To Light the Ways of Time thus: “Brooks was convinced that the main purpose of a college was education – and matters that tended to get in the way of the educational process, whether Greek-lettered fraternities or athletic extravagances, were usually dealt with forthrightly” (p. 150). With his passing in 1931 came the assumption of Pat M. Neff as President of Baylor in 1932. President Neff shifted the focus of the university from an emphasis on a classroom-based education of the person to a more balanced development of the individual both inside and outside the classroom (Baker, 1987).

“What is a Student?”

Neff’s presidency brought a refusal “to let students be excused from chapel. This was ‘his class.’ He decided every element of each session, and attendance was mandatory for all members of the Baylor family – students, faculty, and staff” (Baker, 1987, p. 158). As the primary speaker in Chapel, Neff often used the platform to talk about the importance of the educated man and woman. He used his position to espouse his beliefs to the university community and to define what a proper individual is and what a student should be. According to Baker (1987), Neff “firmly believed that the time students spent…listening to his speeches…could be valuable in helping them turn their thinking to the higher and the better things in life” (p. 158).

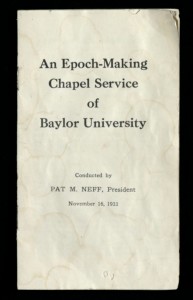

Photo Courtesy of The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Neff maintained a firm ideal of what a student should and should not be. This ideal is clearly defined in his “Epoch-Making Chapel Service” on November 16, 1933. Neff called a special chapel service and had it recorded for future reference. He also asked that members of the board of trustees be present and seated them on stage behind him as he spoke. In this chapel he said:

“If Baylor does not stand for something besides that which students get out of books, then there is no justification for it’s existence. Education is forty per cent academic; sixty per cent atmospheric…. Baylor must be permeated and environed with an atmosphere that stimulates and inspires. During this period of depression, when spiritual affairs have gone tumbling with stocks and bonds, there must be in Baylor no moratorium on morals. Character must be rated higher than curriculum. Our intellectual mechanics may slip a cog, but our moral dynamics must hold, or the University goes to its ignomonious doom” (1933, p. 6).

This view of the purpose of a college and its goals being more than scholastic achievement correlated with an emergent view of college presidents during the time.

Neff went on to address what a Baylor student would be and what a Baylor student would not be. Specifically, he addressed four points of student behavior. First, Neff (1933) attacked the practice of hazing on Baylor’s campus, saying it “represents a pagan spirit and is a brutal, cruel practice” (p. 7). Neff was concerned for the safety of his students, and he would not tolerate an atmosphere of fear at Baylor; in this chapel, he would make hazing strictly forbidden at Baylor. Second, he condemned the consumption of alcohol by Baylor students, saying, “What a sad and sickening sight it would be to see a student, in a drunken delirium fumbling and stumbling over this campus…” (p. 7). The use of alcohol would be forbidden on Baylor’s campus and students found drinking would be dismissed. The third point addressed a student’s propriety, specifically addressing the students’ behavior in chapel.

“Without regard to whether you approve or disapprove the thing that is said or done from this platform, you students are going to be quiet and attentive. If you have not heretofore been taught to be decent and respectful when others are speaking, reading, or singing, you will learn it here or go home…” (Neff, 1933, p. 8).

Neff felt strongly about the idea that students would learn the propriety of person and character, either by choice or by force, at Baylor, with no tolerance given to those who would speak out against the programs that he himself had designed. Finally, Neff (1933) addressed the idea that “The constituted authorities and not the students, are going to run Baylor University….” (p. 8). Again, this was an emphasis on character. Neff felt strongly that while a developed mind was important, a developed character was vastly more valuable.

Photo Courtesy of The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

In this same chapel service, Neff would publicly expel eight students for various crimes of character that he had just defined and asked that students who disagreed with his rules or policies leave Baylor immediately. Neff (1933) would offer his resignation to the board of trustees if they so desired it, saying:

“If you are not in sympathy with the policies that we are going, now not only to stand for, but the policies that are going to be enforced; if in your judgment we are headed in the wrong direction, I shall not be a stumbling block in your way” (p. 11)

The board would offer their unanimous support of president Neff, rejecting his resignation in favor of his definition of the Baylor student.

This perspective of the importance of developing a student outside the classroom but also restricting and defining so exactly the idea of the propriety of character shows a split understanding of what a student was thought to be. The idea of the importance of development outside the classroom is in direct agreement to the emerging ideals of the Student Personnel Movement as defined by Walter Dill Scott (Biddix & Schwartz, 2012). However, the ideas of propriety and submission to authority correlate more with the concepts of Jeremiah Day exposed over a century earlier in the Yale Report of 1828 (Hofstadter & Smith, 1961). Subsequent reports in the Lariat would also offer glimpses of strong student support of Neff (March, 1933, November 17). In this chapel service, Neff offered a clear definition not only of the nature of Baylor University but of the administration’s expectations for students.

The Student Personnel Bureau

In the fall of 1935, Neff would create Baylor University’s first Student Personnel Bureau, headed up by Dr. Iva Cox Gardner, professor of psychology. According to a Lariat article discussing the new bureau, Dr. Gardner had been doing student personnel work and study for five years before the office was created (Stewart, The Daily Lariat, 1935, October 22). The new department was introduced at the fall orientation where new students were separated among 95 upperclassmen into groups of five or six. According to the Lariat, “The installation of this type of orientation marks its first trial in any Texas school…” In the same article, Dr. Gardner would describe the work as “Superseding the old form of orientation exercises in chapel, this work enables the new students to seek aid in solving their problems in adjusting from students who have overcome these same difficulties themselves.” The bureau took control of the orientation program at Baylor, adding a more personal touch to the orientation process. According to the Lariat, Neff offered a report of the new department with great excitement to the Baptist General convention of Texas (Reaves, 1935, November 8).

Dr. Gardner would work with students both individually and in groups. She helped to tackle personal problems and advise students of both genders. She also advised a group of student leaders who in turn would individually interview and advise freshmen that had been assigned to them. At the end of the fall quarter, the Daily Lariat announced that the department would be continued (Reaves, 1935, December 13). Dr. Gardner would report great gains and results from the work of the student leaders, as well as reaching approximately 250 students herself. For the spring, she planned more thorough training for her 95 student leaders (Reaves, 1935, December 13).

Photo Courtesy of The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

January 24th, 1936 brought the announcement that the work of the Student Personnel office would be expanded, and more student workers would be added (Reaves, 1936). “Students are not bad. They merely (g)et on the wrong path and need someone to direct them and show them how to be happy in a better way,” Dr. Garner would say in an interview with the Daily Lariat (Stewart, 1935). The article expands the description of the student personnel office as more than simply a place for freshman to receive advice and counseling:

“The purpose of the new personnel bureau… is to show the right path and help students help themselves. There is no punishment on discipline, in the bureau…. Disciplinary measures have been avoided more times on Baylor campus that the university will ever know… The students were reached and made to see their wrong and change themselves.”

This attitude and approach to students exemplifies a marked difference in the way that students and student discipline was considered and carried out. This was a departure from the more harsh approach of Neff and allowed a more grace-centered process. Indeed, where Neff effectively silenced the voice of the students and forced them into unquestionable submission, this bureau looked beyond the situation and explored the more complex underlying issues of student misbehavior. In May of 1936, the Daily Lariat announced that the Bureau would be added to the Bulletin for the upcoming year, solidifying its position within the Baylor culture (Reaves, 1936, May 1).

The Bureau as Part of the Baylor Community

In the Baylor Bulletin of 1936-1937, student personnel work is described:

“as that which helps the student to make satisfactory progress in his emotional, educational, and vocational life. The objectives of the personnel work are to study the present status of the individual from the point of view of contributory causes which have made him what he is, and to give to him the assistance necessary for removing obstacles which interfere with progress (1936).”

Additionally, the Bulletin description includes an explanation that the office works within the classroom as well as without, with various professors and administrators. It also details the way that the bureau analyzes students and works with them, as well as their work with orientation. The last line of the entry explicitly states that the work of the bureau “is directly responsible to the President of the University” (1936). This shows the many facets that Baylor chose to approach students through. Additionally, it shows the importance of the work of the bureau to Neff.

The Personnel Point of View at Baylor

Though this office was well underway, it was not until 1937 that “the Committee on Problems and Plans in Education of the American Council on Education (ACE) create(d) a professional identity with the publication of the Student Personnel Point of View (SPPoV)” (Alleman & Finnegan, 2009, p.17). It was a foundational publication that focused not only on what the concept of student personnel work was, but where the profession as a whole was going. This article affirmed the work that the personnel bureau was already doing. In the same year, Dr. Gardner, now in her third year as the head of the student personnel bureau, gave a speech detailing the work of the bureau at Baylor in relation to the SPPoV.

“Baylor University, the oldest institution of higher learning in Texas, has through all the years retained possibly more than most other institutions of her kind a personal interest in her students….Baylor University has always maintained the personnel point of view. Dr. Esther Lloyd Jones of Columbia University says, ‘The personnel point of view is not in opposition to a cultural philosophy, but it maintains an emphasis that is educationally sound: that transmission of culture can be most effectively accomplished if the unit vehicles of our culture – our individual students – are thoroughly understood in their goals, their abilities, their weaknesses, and their present and future potentialities.’… It is not strange that Baylor University, with the personnel point of view, should be the first institution of higher learning in Texas to initiate the personnel work and thus make concrete this point of view (Garnder, 1937).”

This speech makes clear Baylor’s redefinition of the student. No longer was a student completely subject to the definition of the president, but the student was more complex, more individual. The student was no longer a technical being, adjusted by the system of the university. Rather, a student was an adaptive being, requiring a holistic approach to affect the pattern of thought, response, and perspective.

At this point, not only was the bureau responsible for the orientation program, but also offered personal counseling services, academic/career counseling services, testing services, study skill workshops and various other services. Indeed, the bureau was a highly active and highly valued institutional asset. Furthermore, the bureau would continually rely on the primary leadership of students in its programs.

Suggestions

While the personnel bureau offered a broad range of services, people from around the campus offered their suggestions of programs and services that the bureau could add. One such suggestion was that the bureau offer a dating program to students that had a difficult time meeting or conversing with others. This suggestion came after the University of Chicago began offering a similar service to their students through their personnel office. However, Dr. Gardner thought that that type of program would be superfluous at Baylor as “it is an age-old tradition and custom for the students to speak to everyone they meet on the grounds” (Provence, 1937, March 16).

Conclusion

Originally establishing a culture of forced compliance to rules within the context of holistic student development, President Neff saw the value of the addition of an office that would serve the students in ways that had not yet been offered at Baylor or any other school in Texas. Baylor would pave the way for student personnel work in Texas and would continue to invest and expand the bureau, refining its purpose, objectives, and processes. The bureau would come to be one of many defining aspects of the Neff presidency, enhancing his vision and execution of enhancing the student outside of the classroom as well as inside the classroom.

References

Alleman, N. F., & Finnegan, D. E. (2009). “Believe you have a mission in life and steadily pursue it”: Campus YMCAs presage student development theory, 1894-1930. Higher Education in Review, 6, 11-45.

Baker, E. W. (1987). To light the ways of time: An illustrated history of Baylor University 1845-1986. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor University. (1936). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Biddix, J. P. & Schwartz, R. A. (2012). “Walter Dill Scott and the student personnel movement. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 49 (3). 285-298.

Gardner, I. C. (1937). “Baylor University in individualized education.” (Speech). Pat M. Neff Collection (Series #5, Box #26, Folder #2). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Hofstadter, R. & Smith, W. (1961). American higher education: A documentary history (Vols. 1 & 2). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

March, C. (1933 November 17). “Student forum.” (A letter to the editor). The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/20460/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Neff, P. M. (1933). “An epoch-making chapel service of Baylor University.” (Stenographically reported. Printed by order of the Trustees.) The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Provence, H. (Ed.). (1937 March 16). “Pros, cons of date bureau discussed by Dr. Gardner.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/35762/rec/15. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1935 September 17). “New orientation form introduced.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/35906/rec/5. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1935 November 8). “President Neff’s convention report shows Baylor’s great progress.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/35857/rec/8. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1935 December 13). “Personnel service will be continued.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/35549/rec/12. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1936 January 24). “New plans talked for personnel unit.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/35679/rec/14. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Reaves, R. (Ed.). (1936 May 1). “Baylor will use ‘D’ as minimum for pass.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/34913/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Stewart, E. (1935 October 22). “Are so-called ‘bad’ students really bad?” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/34898/rec/8. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Thelin, J. R. (2011). A history of American higher education (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.