Baylor University: Female Advocates for Access 1941-1950

Within the time period of 1941-1950 it is easy to think about access in relation to the GI Bill and the effects that such government programs had on men’s ability to access a quality education after serving their country. On the other hand, the World War II era was also a period of great strides for women in relation to access and involvement in education, military service, and career options. According to the 1942-2943 Baylor Bulletin, Baylor University has long supported the opportunity for co-education in order to understand and appreciate the opinions and views of both genders. Further, Baylor University has always valued the participation of both men and women inside and outside the classroom (Baylor Bulletin, 1942-1943). It is through this commitment to co-education that Baylor University promotes the development of students with characteristics of good will, harmonious living and serviceable citizenship (Baylor Bulletin, 1942-1943). Baylor University’s longstanding commitment to coeducation in addition to the influence of various advocates for access, helped pave the way for increasing access to education for women on Baylor’s campus.

Baylor Climate: Co-Education and WWII

Although Baylor University has long touted its commitment to co-education, such education of men and women was far from the standards of equality that are enforced today on Baylor’s campus. According to the Baylor Bulletin from 1942-1943 (vol. 45), the requirements for housing varied between men and women. Both Baylor University men and women were required to live in suite-style dormitories, or with roommates, in order to foster community, but men had the option to live off campus while women did not. Further, women’s educational and housing requirements included church service and Sunday school attendance each week, whereas there is no mention of such requirements for men living on or off campus (Baylor Bulletin, 1942-1943).

Educationally, men and women were barred from taking certain classes at Baylor University. Aviation classes were specifically held for men, and were even further narrowed by such classes being prescribed as an air corps prerequisite. On the other hand, men were not allowed to participate in dance classes on Baylor’s campus. Although the Baylor Bulletin from 1942-1943 refers to the University’s commitment to co-education, it also showcases an unequal commitment to educational and living standards for men and women. Unbeknownst to the writers of the 1942-1943 Baylor Bulletin, Baylor University would soon be integrating various single gender courses and policies, especially in support of the war effort.

The beginning of the United States’ involvement in World War II was experienced in various ways on the Baylor University Campus. The December 9th, 1941 edition of the Baylor Lariat focuses on the various ways in which students experienced Pearl Harbor and its effects on the nation and on the Baylor campus. December 9th was registration day for the upcoming spring term, both men and women recall taking their class choices much more seriously than in previous terms, knowing that an impending draft or call to the workforce may be prioritized over their education (Baylor Lariat, 1941, 43). In the spirit of co-education and the impending war, access to education was expanded for women, especially in areas of nursing, mechanics and aviation (Baylor Round Up, 1943) The overarching patriotic climate on Baylor’s campus that emerged from a national tragedy enabled Baylor men to continue their education in the reserves, and allowed Baylor women to pursue new avenues of higher education that would eventually lead to access in military service and in the workforce.

Murray and McLellan: Advocates for Access

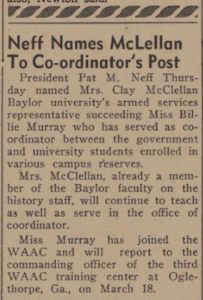

Although practices for co-education may have been perceived as unequal in some arenas, there were multiple Baylor University women who played a role in helping women gain access to various fields of education, including Billie Murray and Merle Mars (Clay) McLellan Duncan. These two female leaders of the Baylor community, play a part in aiding the war effort of the era, as well as helping women gain access to traditionally male dominated curriculum. Murray and McLellan were catalysts for access during this time period. Billie Murray preceded Clay McLellan as the Armed Services Representative on Baylor’s campus. Both Murray and McLellan played vital roles on and off campus in assuring access to education for service men and women.

Murray worked most with Women’s Army Auxiliary Core (WAAC) and its goal to recruit women for the armed services. This unprecedented access to service and job training through the US government showcased the commitment of Murray, Baylor and the nation, to providing access to areas of education, jobs and eventual careers that were never before accessible. Eventually, Murray volunteered to serve in WAAC herself and left her post in the hands of McLellan. Merle Mars (Clay) McLellan Duncan was most often referred to as Mrs. Clay McLellan, as noted in letters from men in the armed services, as well as in her own biography for the American Association of University Women (AAUW). McLellan had returned to teaching at Baylor after her attendance as a student in the late 1930’s. McLellan was appointed by Pat Neff in 1943 to be the Armed Services Representative to campus, the successor to Mrs. Billie Murray (Baylor Lariat, 1943, 23). In 1944 McLellan was elected to the presidency of the Texas Chapters of the AAUW (McClellan, 1944). McLellan’s involvement in WAAC allowed her to aid Baylor women in gaining access to curriculum and courses previously only available to males. Enrollment in these courses enabled female Baylor students to serve in the war effort as well as gain valuable job skills that could be utilized after the war. In her role with the AAUW, McClellan aided Baylor women in gaining access to graduate school education. Further, McLellan also aided the women of Texas in access to education and career opportunities; especially those from an impoverished background, or women displaced by the war effort.

Courtesy of the Texas Collection

Courtesy of the Texas Collection

Billie Murray

Murray’s involvement in the WAAC was first endorsed by the President of Baylor University, Pat Neff (Neff, 1940). It was Neff (1940) who recommended Murray to serve as the campus liaison between Baylor and the national war effort. It was Neff’s goal to retain Murray as a valued member of the Baylor campus, but to also allow Murray to pursue her goals in aiding the war effort (Neff, 1940). Although not stated by Neff, his insistence upon recommending Murray to serve in WAAC but keep her employed at Baylor, might be seen as a possible endeavor to help create access for women specifically on Baylor’s campus.

Photo Courtesy of the Texas Collection

Photo Courtesy of the Texas Collection

Murray’s appointment to this position allowed for the women in the Baylor community to pursue leadership opportunities in relation to the war effort through many facets of involvement. Although the WAAC did not have any educational standards or requirements, courses of study that were encouraged by the WAAC included the sciences, physical education, math, history, business, and economics. Further, WAAC involvement was well known for producing a quality of leadership that the armed services expected (Baylor Lariat, 1942, 26). Not only did WAAC recruitment boast of its involvement with the armed services, but it also noted that the training received while being a member of WAAC would serve women well in the workforce (Baylor Lariat, 1942, 26).

Many women initially questioned the need for WAAC as well as their ability to serve in the organization (Baylor Lariat, 1943, 67). The Baylor Lariat and Murray were the largest voices for involving Baylor women in the WAAC organization. One the largest recruitment advertisements from the Lariat was in the February 17th, 1943 installment of the Baylor Lariat. This ad utilized ¾ of the page of the newspaper and addressed concerns about need, winning the war, educational standards, salary, types of jobs, promotion opportunities, and the physical requirements. The article, promoted by the 67th volume of the 1943 Baylor Lariat, aided in the recruitment of women into the WAAC program. This article not only supplied a call to action for the patriotic women of Baylor but it also addressed initial reservations that women had about joining WAAC (Baylor Lariat, 1943, 67). The importance of ads such as this lies within the influence that propaganda played in the World War II era. Uncle Sam saying we want you and Rosie the Riveter were national characters to support the war effort and the WAAC ads in the Baylor Lariat provided the same type of call to action on campus as was occurring in the national arena.

Murray aided in the recruitment and advertisement of WAAC in many ways; one of the most hands on campaigns was Murray’s duty to host the WAAC guest speakers who traveled to Waco to speak to Baylor and Waco women. Murray often hosted guest speakers from national WAAC offices that helped to inform and recruit Baylor and Waco women into the WAAC. Informational sessions were hosted both on and off campus in order to provide the most access to the meetings for all women residing in Waco. In November of 1942, Lieutenant Jessie M. Anthony of Des Moines, Iowa was the guest of Murray during her stay in Waco (Baylor Lariat, 1942, 26). During Lt Anthony’s trip, Murray and Lt. Anthony helped to provide women with information about WAAC and aid in the active enlistment into WAAC and the military as a whole.

Murray’s commitment to WAAC, her role in serving as the armed services representative, and her support of the war effort was so strong that on March 9th of 1943 Murray herself became a member of WAAC and enlisted in the military. The announcement was made by the Baylor Lariat on the 10th and Murray reported to training in Dallas on March 16th, 1943 (Baylor Lariat, 1943, 73). The same edition of the Lariat noted that over 500 men owed their standard of education to Billie Murray and her insistence that a Baylor man “can be just as patriotic while serving as an officer, and a lot more comfortable” (Baylor Lariat, p. 2, 1943, 73). Although Murray helped in recruiting purposes for the WAAC that enabled women to pursue higher education to varying degrees, it is imperative to also note her commitment to the education of servicemen at Baylor.

Merle Mars McLellan Duncan

As the armed services representative, it was McLellan’s duty to see that all men in the reserves received the full depth and breadth of education possible before being called to service. It was also McLellan’s duty to aid in WAAC recruiting in the same fashion as Billie Murray. The WAAC allowed women to enlist in the army and serve overseas in many of the areas previously only held by men.

Photo Courtesy of the Texas Collection

Photo Courtesy of the Texas Collection

During McLellan’s faculty and staff time at Baylor she taught Latin American studies, served as Baylor’s armed services representative, was a member of the WAAC, was editor of the McLennan County Handbook and served as President of the Texas AAUW Chapters (Delta Kappa Gamma Society International, 2015). McLellan was honored in 1944 by Delta Kappa Gamma Society International, and given status as an honorary member of the Texas State Organization (Delta Kappa Gamma International, 2015). Delta Kappa Gamma Society International awarded McLellan this status in order to show recognition to women who rendered notable service and contributions to the statewide significance to education and/or women.

McLellan’s greatest commitment to bettering access for women on Baylor’s campus was seen in her involvement in the American Association of University Women (AAUW). McLellan was elected President of the Texas Chapters of the AAUW in 1944 and was adamant about providing graduate study and involvement for women in the program as well as providing basic education and necessities to women in need in Texas. Further, McLellan was also concerned with aiding any women in the AAUW who had been transferred to Texas as part of the war effort (McLellan, 1944). The 1944 Texas Division Newsletter, authored by McLellan, lists aspects and goals that the organization could focus on throughout the year; many of these aspects focused on access to education and employment.

In the 1944 AAUW Newsletter, McLellan included reports from other AAUW chapters from around the state of Texas. Many reports showcased a focus on providing and advocating for women to receive equal pay for equal work, providing education for Hispanic children in order to reduce juvenile delinquency, a commitment to the betterment of African American lives, and the commitment to enabling women to serve on governing boards of colleges and public schools (McLellan, 1944). McLellan’s faculty and staff position at Baylor allowed for the recruitment of Baylor women into the organization. Further, McLellan’s influential position in higher education aided her and the 3600 members from 44 chapters of the Texas AAUW to provide access to education for women in various community initiatives across the state as well as aid in providing access to graduate education for women (McLellan, 1944).

Women were recruited from the Baylor undergraduate population into the AAUW by McLellan with the incentive of receiving graduate coursework credit, and by allowing newly recruited women to aid in the implementation of the many programs encouraged by the AAUW. McLellan encouraged research fellowships for graduate student women that also related to the AAUW and its purposes (McLellan, 1944). In 1945, Baylor played host to the Texas convention for the AAUW. In a letter from McLellan to Neff on April 24, 1945, McLellan thanks Neff for allowing her to host the AAUW convention on the Baylor campus. The consent from Neff to allow McLellan to host the AAUW convention on the Baylor campus may further point to a personal dedication to provide access to opportunities for Baylor women.

McLellan’s combined involvement in the WAAC and the AAUW enabled her to improve access for women in education in various areas. Involvement as the armed services coordinator and aiding in WAAC recruitment allowed McLellan to reach out to Baylor women and provide them with resources to support themselves and their country. The education and training that WAAC provided to university women helped to pave the way for the improvement of women’s lives in their pursuit of higher education. Additionally, training provided by WAAC would continue to serve women in the workforce after the end of World War II (Baylor Lariat, 1943, 67). Further, McLellan extended access to higher education through her work with AAUW. In recruiting Baylor women straight from their undergraduate careers and enticing them with graduate program credit coupled with the moral duty to spread education far and wide, McLellan improved access to education for women not only on campus and in Waco, but also across Texas.

New Programs on Campus

In relation to the war effort, women were often encouraged to study nursing, and Baylor women were no exception. According to the Baylor Lariat, on November 5th, 1941, a home nursing course was offered for Baylor women that was sponsored by the Red Cross. Over 111 women signed up for the home nursing course within three hours of its announcement (Baylor Lariat, 1941, 30). It is clear to see that Baylor was providing women with access to education but also, that women were seeking education for themselves and for service to their country. The home nursing course was deemed a “preventative against an inadequate number of trained nurses for the civilian population in the case of war” by the Surgeon General of the United States Army (Baylor Lariat, p. 1, 1941). With support from Dean of the School of Nursing, women were given the opportunity to quickly move through nursing courses in order to serve in the war effort. Not only were women more often enrolled in nursing classes but women were also enrolling in classes previously restricted to all male enrollment; including classes such as aviation and mechanics (Round Up, 1942). Photos from the 1942 Round Up showcase the newly implemented course involvement. Also in the 1942 Round Up is a message from Helen Lehman, the Dean of the School of Nursing. Lehman addressed the students in the school of nursing, praising them for their patriotic undertakings and ability to serve the world both within the United States and abroad. Above all, Lehman congratulates nursing students on their endeavors to preserve the American way of life (Round Up, 1942).

Photo Courtesy of the Texas Collection

Photo Courtesy of the Texas Collection

In 1943, Lehman retired and Zora M. Fiedler was appointed as the Dean of the School of Nursing (Garner, 2010). It was Fiedler’s goal to establish a baccalaureate school of nursing on top of the training and certificate programs that were currently being offered by Baylor (Garner, 2010). Fiedler reorganized the entire school of nursing in order to provide a better education for students and allow access to a more comprehensive program of nursing. Fiedler created both diploma and degree courses with varying requirements of clinical hours and classes (Garner, 2010). These variations only increased access to an array of classes for Baylor nursing students. In 1954 the first baccalaureate degrees in nursing were awarded by Baylor University; Fiedler retired in 1951 after the full implementation of the program (Garner, 2010).

Both Lehman and Fiedler showcase their commitment to providing access for women in nursing and giving students the opportunity to access a first class education. Lehman, who governed in times of war, focused on encouraging students to pursue such patriotic duties (Round Up, 1942). Fiedler, who governed more so in an era that warranted a pursuit of achievement and knowledge, provided access to education for students who wished to pursue a career in nursing (Garner, 2010).

Conclusion

Murray, McLellan, Lehman and Fielder provided various programs to individuals that helped increase access for women both in education and in the changing job market of the era. Billie Murray, in her relation to WAAC helped give women access to leadership and educational training that provided them an opportunity to serve themselves and their country. WAAC was such an influential aspect in Murray’s life that she enlisted in the program herself and became a military woman. Clay McLellan also served in recruitment purposes for WAAC, but also served Baylor women and the community of Waco in her involvement in the AAUW. McLellan gave Baylor women access to graduate education and programming. McLellan also extended educational access into struggling populations of Waco and of Texas. Baylor’s commitment to the nursing program and their coordination with the Red Cross, even before formal war was declared, showcased not only the university’s advanced thinking but also the patriotism of Baylor women and their desire to serve their country and provide themselves with education and access to a career.

Between 1941-1950, many accounts of history are related to World War II, the GI bill and the various ways men served themselves and their country; but it was also an important era for improving women’s access to education, military service, and future career paths. Individual faculty and staff as well as Baylor University itself provided women with avenues of support and involvement so that women could gain access to a whole new world of possibilities. Murray aided in recruiting women into the WAAC program to serve their countries and themselves. McLellan utilized her roles at Baylor and the AAUW to provide educational opportunities to women on campus and in the community. Lehman and Fielder played roles in expanding the nursing school and ensuring that Baylor nursing students were receiving quality education that would serve them in the workforce. In an era that was male centric, these women made improvements in access to education that changed the landscape and culture of the Baylor University campus forever.

References

Baylor Lariat, (1941). November 5th – number 30. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/32559/rec/5

Baylor Lariat, (1941). December 9th –number 43. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/32495/rec/1

Baylor Lariat (1942). November 5th – number 26. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/33224/rec/3

Baylor Lariat (1943). February 17th – number 67. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/33512/rec/1

Baylor Lariat, (1943). March 10th – number 73. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/33357/rec/5

Baylor Lariat, (1943). March 12th – number 74. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/33387/rec/19

Delta Kappa Gamma Society International (2015). Texas State Organization honorary members since 1930: Recognizing women who have made contributions and rendered notable service of statewide, nation or international significance to education and/or women.

Garner, L.F., (2010) Louise Herrington School of Nursing. Handbook of Texas Online. Published by the Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/kbl24

McLellan, C., (1944) Texas Division Newsletter. American Association of University Women.

McLellan, C., (1945) Letter to Pat Neff. Box 156, Folder 1. Pat M. Neff Collection, Sub Series 17: Baylor Materials, Sub-Subseries 6: Faculty Correspondence. Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Neff, P.M., (1940) Letter to Billie Murray. Box 156, Folder 13. Pat M. Neff Collection, Sub Series 17: Baylor Materials, Sub-Subseries 6: Faculty Correspondence. Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Round Up, (1942). http://contentdm.baylor.edu/cdm/ref/collection/tx-annl/id/28996

Round Up, (1943). http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/ref/collection/tx-annl/id/22311