Introduction: The Context of Black Exclusion at Baylor

In 1954 Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas began a decades-long process of the racial integration of public schools. Thelin (2011) notes that while the University of Kentucky voluntarily began to integrate in 1949, many universities did not officially admit black students until litigation forced them against their will, often beginning with schools and programs unavailable to black students through black institutions, creating an obvious inequality of opportunity. Progress towards integration was occurring nearby Waco in the 1950s: As reported in a Baylor Lariat reprint of an AP Bulletin, even before Brown v. Board, the decade opened with the Supreme Court demanding that the University of Texas admit a black law student (“U.S. Supreme Court,” 1950). In the fall, fifteen black students were reportedly enrolled, and the university claimed all would have equal access to sporting events, libraries, and cafeterias (“Excerpts,” 1950).

Of course, the courts demanded the desegregation of public institutions, with private schools retaining the freedom to discriminate, a right which Baylor did not voluntarily relinquish until 1963, despite unanimous support for integration from the Student Congress in 1955 (Baker, 1987, p. 241). It would be easy to assume Baylor in the 1950s, as part of the segregated South, was exclusively white in both its population and associations. Baylor was not entirely devoid of ethnic diversity, however, and even though that diversity did not include black students, there were meaningful points of contact between Baylor and the black community. These initial interactions demonstrate both the hope and tragedy of the 1950s, a time during which goodwill and friendship in small doses were insufficient to overcome the larger divisions of Southern society.

People of Color at Baylor

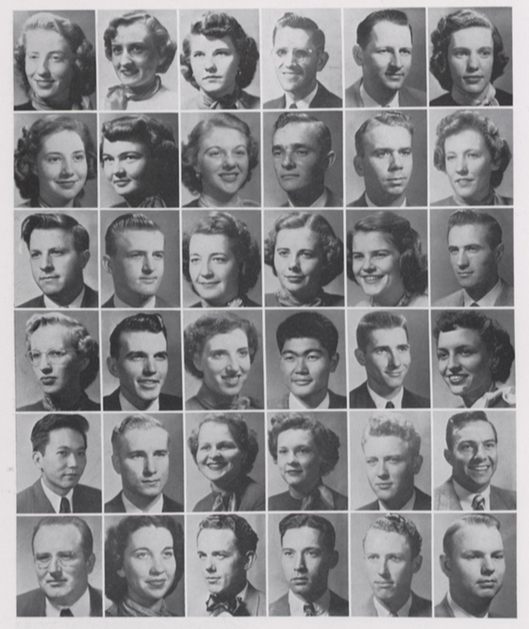

At the beginning of the 1950s, Baylor was open to a number of ethnic minority students, both domestic and international. The Lariat reported that in 1951, 46 students were from other countries (“19 Per Cent,” 1951), although at the time, this included students from territories such as Hawaii and Puerto Rico. While some of Baylor’s international students were of European descent, a look at the 1950 yearbook proves that a number of students of color were studying among their white counterparts as the decade began. Students came from Shanghai, Hong Kong, Hawaii, Jerusalem, Honduras, and Mexico (Buchanan, 1950).[1] While neither name nor appearance are always fully reliable indicators of ethnicity, there also appear to have been several Latino students from Texas, as well as a few Asian American students (Buchanan, 1950).

While Baylor was clearly majority white throughout the 1950s, the dozens of identifiable minority students point towards a meaningful degree of ethnic inclusiveness at this time. Baylor had not emphasized white racial purity to the extent that no students of nonwhite backgrounds could attend, and indeed at least some students of color found Baylor to be welcoming. Tashio Ito, a 49-year-old Japanese student visiting Baylor to take English classes in 1950, reportedly found Baylor and Texas in general to be quite friendly (Bryant, 1950).

Also notable is the generally positive tone of Baylor towards other international guests of color. Baylor’s Press Relations department found it newsworthy to report on the presence of a new Korean doctoral student, Chon Dong, in 1952 (Bryant, 1952), as well as brief visits from Indonesian educators in 1957 (Markham, 1957) and Malaysian government officials in 1960 (Markham, 1960a). Visiting Indian academic S. Gopal Hulyakar was allowed to give lectures to Baylor students in 1959 (Bishop, 1959), and Prof. James K. Mau, was a visiting professor from Hong Kong Baptist College in 1960, as part of a two-way exchange of personnel (Markham, 1960b). Even as far back as 1939 a Japanese guest was the subject of a press release, with Baylor admitting the man made corrections to American mistakes at an exhibit including Japanese translations of Robert and Elizabeth Browning’s works (Baylor University, 1939).

In all of these articles, Baylor assumed the presence of international visitors of color to be something neutral or even positive which would be of interest to alumni and the broader community. While not proving campus guests never faced racism or that all friends of the University were thrilled about this cultural exchange, it is clear that such guests were not significantly controversial: there was evidently little risk of shame or drama in reporting the presence of guests of various ethnicities. In fact, Baylor president W. R. White seemed to find international students to be a point of pride for the university: “The association of these students with our native born in classes, on the campus, and in dormitories adds much to the growth of the ‘one world’ conception of international relations,” he said. “Our foreign students make a distinct contribution to campus life” (“19 Per Cent,” 1951).

Baylor Connections with the Black Community

Despite an enthusiasm for at least some forms of diversity on campus, one population of students and honored guests is notably missing from Baylor in the 1950s: those of African descent. The historical context of slavery and segregation in the South partially explains why this final barrier of inclusion would be the most difficult, allowing Baylor to treat those of Asian and Latin American descent so differently from those of African heritage without debilitating cognitive dissonance. However, just because there were not African or African American students or visiting professors does not mean black people never set foot on campus or that Baylor lacked interactions with the broader black community.

One of the primary ways students interacted with African Americans in the Waco community was through the Friday Night Missions, a local outreach by students, which began in 1941 and involved VBS-style programming for children and youth in the area, a number of them black or Latino (Baylor University, 1965). One could suspect the Friday Night missions of paternalism, and it may be that some community members perceived the effort of the white students in this way. At the very least, however, that was not the feeling of all the children participating in the activities. One such individual was Choice Richardson, a 1966 African American junior who claimed that he had chosen to attend Baylor because of his relationship with the students of the Friday Night Missions when he was a child (Rothe, 1966), presumably in the 1950s. As a student, he even became involved in the Friday Night Missions himself (Rothe, 1966), giving back to the community by offering other children the same experiences that had been so formative in his own life.

Another outreach to the black community focused on the fine arts. In 1951, a drama student led the “Negro Children’s Theatre” program that was part of the larger Children’s Playhouse at Baylor (Bryant, 1951), and in 1957 the “Waco Negro Teen-Age Theatre” was still performing with the support of Baylor students under drama faculty supervision (McHam, 1957). This program, focused on self-expression and arts appreciation, demonstrates a very small way in which even one Baylor department could volunteer their time and talents to support Waco’s black community—in this case by offering extracurricular opportunities for African American children. While not without the risk of feeding a white savior complex on the part of students, these pint-sized efforts toward compassion and connection were a meaningful first step toward true fellowship and cooperation with the black community.

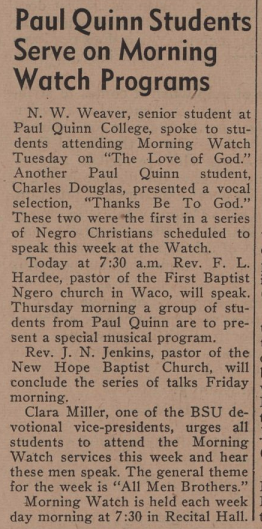

The exchange also went in the other direction, which showed a willingness of Baylor—albeit limited in scope—to also receive from the talents of African Americans, particularly in a religious setting. For example, the Baptist Student Union invited black musical guests to perform at the Baylor Religious Hour, a “nondenominational service to which all students are invited” (“Howard Butt,” 1949). In 1949, for example, the Lariat reported that, “the Junior Echoes, a colored sextet, from Hearne,” would be providing the music at that week’s meeting (“Howard Butt,” 1949). Another service called Morning Watch, also sponsored by the BSU, gathered weekday mornings and invited several guests from Waco’s HBC Paul Quinn College to preach or sing during a week themed “All Men Brothers” in 1951 (“Paul Quinn,” 1950). This programming explicitly promoted a notion of universal brotherhood and allowed African Americans positions of teaching authority, albeit temporary. These interactions show the willingness of clusters of Baylor students to interact with black Wacoans—at least in certain contexts and roles—as fellow bearers of the divine image.

W. R. White & Bishop College

Interestingly, Baylor President W. R. White had his own meaningful ties to the black community, despite being marred by a lack of full commitment to their cause. Chief among these was his membership on the board of Bishop College, a black college located in Marshall, Texas. Bishop captivated White’s interest in the 1930s—a relationship he claims significantly aided Bishop in building an alliance with white Baptist conventions and donors due to White’s role as Executive Secretary of the Baptist General Convention of Texas (White, 1951). White even served as president or chairman of the board (the name differing over time) for many years beginning no later than 1949 (Bishop College Board of Trustees, 1949). He also personally contributed small dollar amounts to Bishop’s work among black students, such as a $5 contribution to the bell tower fund (Rhoads, 1950).

White’s relationship with the black higher education community, and thus also Baylor’s, is complicated by questions regarding White’s willingness to treat his acquaintances at Bishop, as well as Waco’s own Paul Quinn College, as fully equal brothers and sisters. For example, in 1950 an E. L. Martin of Martin & Grace General Contactors in Dallas wrote to “Charlie,” Charles R. Moore, chairman of the Board of Directors at Baylor Hospital in Dallas, suggesting that Baylor’s dental clinic care for black patients (Martin, 1950a). He also sent a copy of the letter to W. R. White and to Executive Secretary of the BGCT, J. Howard Williams (Martin, 1950a), demonstrating his faith in all three men to be able to accomplish what he proposed. “As stated to you some years ago,” Martin says, “I feel that some definite and satisfactory provision should be made in the immediate future to give this service” (Martin, 1950a), indicating that he had previously mentioned this possibility to Moore, if not also to White and Williams, and saw no action taken. He then explained that white people are often to blame for their own poor health and hygiene, but black people lack access to basic services and are thus deserving of this opportunity. Additionally, Martin advocates for black students to be accepted into the dental school to help serve their own community. He concludes the letter with an optimistic, “Let’s do something!” (Martin, 1950a). However, it is unclear whether anything was ever done, as no reply from White or the other recipients is attached.

In a short letter sent directly to White with his copy of the suggestion to Moore, Martin refers to his ideas about the dental school and acknowledges White’s power to help make these changes (Martin, 1950b). Martin also reiterates comments from a recent conversation between himself and White (Martin, 1950b): “You heard my remarks at Bishop College yesterday, and on the trip to and from, as to my ideas about taking some young negro preachers and giving them training at the Seminary,” referring to Southwestern. “I think something should be done about this.” Martin concludes, “I do not want to be a disturber but it sometimes requires a disturbance to arouse people out of their lethargy” (Martin, 1950b). White’s simple reply thanks Martin for the letter and the enclosure, states he would be “happy to discuss the matter with Dean Powers when I am in Dallas,” and cordially remarks that he enjoyed their time spent together traveling to Bishop (White, 1950). Interestingly, a 1950 report on ministry to minority groups in Texas indicates that Southwestern did offer an 11-course extension program with over 200 black ministry leaders enrolled (Miller, 1950). Unfortunately, with no reply from White, we do not know whether the students Martin had in mind were encouraged into this second-tier program or how Martin might have felt about such a response.

W. R. White & Paul Quinn College

Similarly, White had a relationship with the administration of Paul Quinn College in Waco, a college connected with the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Demonstrating this relationship, Paul Quinn Publicity Director Charles Carver called on White to give a brief statement of support for the college’s work as they began a new fundraising campaign (Carver C., 1953).[2] “It occurs to me that the educational kinship of Baylor and Paul Quinn might be stressed,” Carver suggested, “but whatever you care to stress will be appreciated” (Carver C., 1953). White responded with a brief statement of the “competent hands” doing a “splendid job” at Paul Quinn, which he describes as “a decided asset to the city of Waco” deserving the “wholehearted support” of the community (White, W. R., 1953).[3] Although White complies with Carver’s request, notably absent are any of the recommended comparisons between Baylor and Paul Quinn which might have communicated that White saw the institutions as something resembling peers. A relationship between White, Baylor, and Paul Quinn is evident, but the exact nature is unclear.

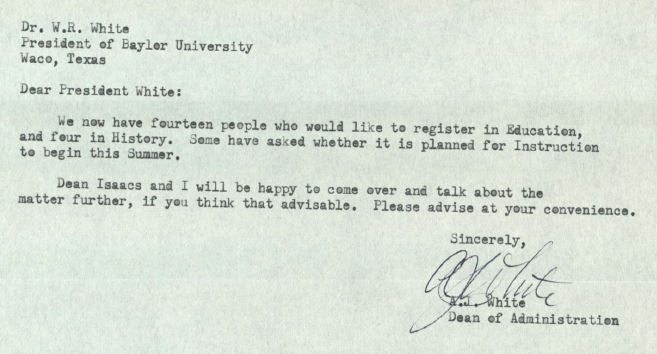

Shedding more light on the quality of their rapport, the previous month, Dean of Administration A. J. White of Paul Quinn had written to W. R. White regarding the possibility of a few faculty members from Paul Quinn taking Baylor courses. “With refernce [sic] to the conversation with you, Dean Isaacs and myself, relative to the possibility of faculty members of Paul Quinn and Teachers of Waco and the vacinity [sic], pursuing courses at Baylor,” Dean White writes to President White, “[u]p to the present, six have indicated a desire to pursue courses in Education, three in History, two in Physical Education, two in Guidance and possibly three, and one in Psychology” (White, A. J., 1953a). Some days later, Dean White sends a follow-up letter, informing President White that there are now fourteen potential students for Education and four in history: “Dean Isaacs and I will be happy to come over and talk about the matter further, if you think that advisable,” he offers. “Please advise at your convenience” (White, A. J., 1953b).

Unlike numerous sets of correspondence between White and his colleagues, the trail always seems to go cold on these sorts of requests. Like E. L. Martin’s suggestions regarding the potential Baylor Dental and Southwestern Seminary students, there is no reply to Paul Quinn archived with these original letters. While an unassailable argument cannot be made from a vacuum, the absence of additional evidence of White’s positive response suggests the reply may have been negative, nonexistent, or at least not something of which he felt it prudent to keep a copy. Perhaps the discussion continued in person rather than on paper; however, the absence of further record rightfully raises our suspicions and tempers our enthusiasm for the partnership between White and his black counterparts at Texas.

“Mediating” Two Sides

Throughout the 1950s, a handful of alumni and board members wrote to President White, unhappy with society and often unhappy with Baylor. During this tumultuous time, Baylor constituents disagreed sharply on whether the University was moving too quickly or two slowly toward integration. For some, like Baylor trustee D.K. Martin, Brown v. Board was a “lousy decision” which “ha[d] caused deplorable unnecessary agitation” (Martin, D.K., 1956a). “The Supreme Court decision on desegregation, damnable as it was, did not apply to Baylor University,” he declared in the same letter. Another time Martin copies Dr. White on a letter to Earl Hankamer, in which he states that, “The Warren-Supreme Court decision on Anti-Segregation was the dirtiest slap at the South since the Reconstruction deal and dirt” (Martin, D.K., 1956b). It goes without saying that Baylor constituents like D. K. Martin were not thrilled with the direction race relations were headed in the South and did not want Baylor to become any more inclusive.

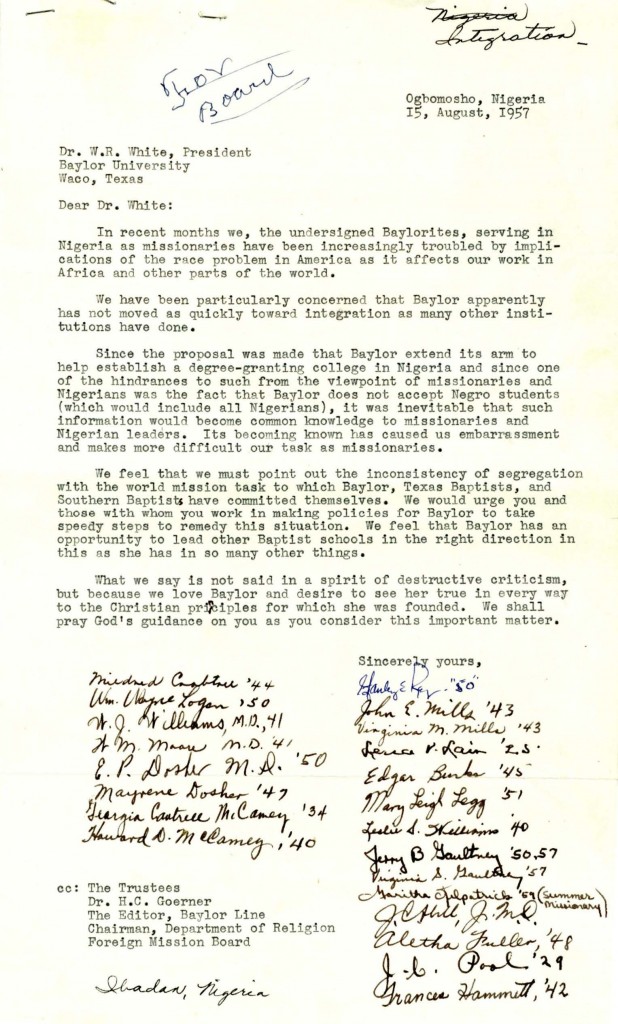

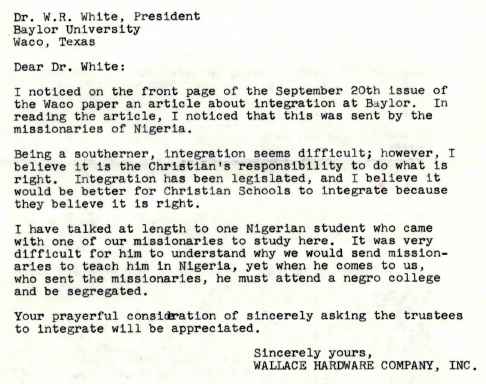

At the same time, advocates for change petitioned Baylor to move faster to desegregate. One of the best examples is that of a group of alumni serving as missionaries in Nigeria who wrote to Dr. White to explain the difficult position in which they found themselves due to Baylor’s stance and how these policies were harming their work among black Africans. “We have been particularly concerned that Baylor apparently has not moved as quickly toward integration as many other institutions have done,” they explained. “Since the proposal was made that Baylor extend its arm to help establish a degree-granting college in Nigeria… it was inevitable that such information would become common knowledge,” which “has caused us embarrassment and makes more difficult our task as missionaries” (Mills, 1957)[4]. This embarrassment likely reached its peak in an incident relayed by to Dr. White by a John D. Wallace of Wallace Hardware Company. “I have talked at length to one Nigerian student who came with one of our missionaries to study here,” Wallace said. “It was very difficult for him to understand why we would send missionaries to teach him in Nigeria, yet when he comes to us, who sent the missionaries, he must attend a negro college and be segregated” (Wallace, 1957). Heart-wrenching and compelling as these letters are to today’s reader, several years remained before Baylor would integrate.

Regrettably, White did not emphasize his disagreements with outright racism but strove to occupy a middle position, mediating two parties. When the BSU conference was held at Baylor in 1955 with black students in attendance, a J. H. Bondeson sent White a newspaper clipping calling this contact, “the MOST DISGRACEFUL THING THAT HAS EVER HAPPENED TO WHITE BAPTISTS, AND BAYLOR UNIVERSITY!” and she continued on a long, loud rant dripping with prejudice (Bondeson, J. H., 1955). White’s unhelpful reply stated, “We were hosts to the B.S.U. Convention. When we invited them, there were no Negro colleges in the B.S.U.” (White, W. R., 1955). In a form letter sent to constituents unhappy with the call of the missionaries to Nigeria to integrate Baylor, White claimed he was not “straddling the fence” but was “occupying a bench, that is, of an arbiter or mediator, so that I can keep extremists on both sides from tearing our people apart” (White, W. R., 1957).

Conclusion

To the twenty-first century observer, White is a hindrance to Baylor’s progress. He may have been a well-intentioned mediator, but he ultimately valued unity between camps of white Baptists more than solidarity with the black community. However, it is easy to judge figures of the past without considering their context. Today’s historian must recognize that in its time the issue of integration was not so far removed from the controversies of our own churches and society, such as women in ministry or LGBT inclusion. White wrote in an article, “We must realize that equally sincere Baptists are on both sides of this issue” (White, W. R., ca. 1956-1957). Although tragic, indeed there were Baptists all across the spectrum, and perhaps that is why Baylor for many years occupied a liminal state between the worst of Jim Crow and the true beginnings of the post-integration era. Important constituents voiced their opinions on both sides, and White pressed forward with the “moderate” position he thought was best for the University as a whole. This course of action minimized the alienation felt by the white Baptists who supported Baylor, but it also diminished Baylor’s moral standing in the eyes of its more progressive constituents.

On the other hand, seeds of change were slowly taking root at Baylor during this decade—perhaps more than some would have pessimistically expected. One can retrojectively find major flaws with many aspects of Baylor’s response to societal changes and Supreme Court decisions, but one would be wrong to think nothing was happening during the ‘50s just because integration was not enacted until the ‘60s. Despite having no black students, Baylor was also not all white, and some members of the Baylor community, including President White, maintained relationships with African Americans locally or within the larger Baptist community. From the student council to alumni on the mission field, a handful of prophetic voices also continued to pressure Baylor to change. In the 1950s, Baylor was only beginning a slow journey toward increased ethnic diversity and concern for social justice; however, it is evident that Baylor made small steps toward racial equality during this decade of disappointment and unfulfilled promise.

[1] See Appendix A for a list of students identified with yearbook page numbers.

[2] It should be noted that although this particular correspondence related to Paul Quinn College, at the Texas Collection, it was located in the correspondence folder relating to Wright’s correspondence with Bishop College. See references below for full citation.

[3] Again, this document occurs in the Bishop College files.

[4] Although the letter itself does not identify a single author, Orba Lee Valentine identifies John Mills as the principal author (Malone, O. L, 1957).

References

19 Per Cent of Baylorites Are Foreign Pupils. (1951, November 14). The Baylor Lariat, p. 2. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/25283/rec/6

Baker, E. W. (1987) To Light the Ways of Time: An Illustrated History of Baylor University, 1854-1986. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Baylor University News and Information Service. (1965, November 11). Baylor University Press Release, 11/11/1965. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/13198/rec/4

Baylor University News Service. (1939, May 9). Baylor University Press Release, 05/09/1939. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/1090/rec/1

Beckham, C. T. (Ed.). (1949). The Round Up. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-annl/id/27246/rec/2

Bishop College Board of Trustees. (1949, May 3). [Minutes of the Bishop College Board of Trustees]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1948-1951. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Bishop, M. (1959, April 25). Baylor University Press Release, 04/25/1959. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/23372/rec/10

Bondeson, J. H. (1955, October 15). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Personal Papers, Accession #BU/142, Box 10, Segregation 1955-1956. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Buchanan, B. (Ed.). (1950). The Round-Up. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-annl/id/26820/rec/3

Bryant, C. E. (1950, October 7). Baylor University Press Release, 10/07/1950. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/2260/rec/1

Bryant, C. E. (1951, September 21). Baylor University Press Release, 09/21/1951. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/2384/rec/1

Bryant, C. E. (1952, September 19). Baylor University Press Release, 09/19/1952. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/1762/rec/4

Carver C. (1953, May 8). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1953. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Excerpts from Other Campus. (1950, September 29). The Daily Lariat, pp. 4-5. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/25046/rec/8

Howard Butt Speaks Tonight at Baylor Religious Service. (1949, November 20). The Daily Lariat, p. 1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/23810/rec/18

Lyle, J. (Ed.). (1951). The Round Up. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-annl/id/23395/rec/4

Malone, O. L. (1957, September 20). [Letter to F. Valentine]. Foy Valentine Papers: The Christian Life Commission- Work Files 1955-1987, Accession 2948, Box 88, Folder 2- Correspondence 1957. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Markham E. E. (1957, May 29). Baylor University Press Release, 05/29/1957. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/7549/rec/2

Markham, E. E. (1960a, August 19). Baylor University Press Release, 08/19/1960. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/10017/rec/15

Markham, E. E. (1960b, September 21). Baylor University Press Release, 09/21/1960. Baylor News. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/4848/rec/7

Martin, D.K. (1956a, March 20). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Personal, Accession #BU/142, Box 3, D. K. Martin 1955-1956. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Martin, D.K. (1956b, March 29). [Letter to E. C. Hankamer]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Personal, Accession #BU/142, Box 3, D. K. Martin 1955-1956. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Martin, E. L. (1950a, May 3). [Letter to C. R. Moore]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1948-1951. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Martin, E. L. (1950b, May 3). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1948-1951.

McHam, D. (1957, May 16). Baylor University Press Release, 05/16/1957. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/7036/rec/2

Miller, A. C. (1950). “Seventh Annual Report: Ministry with Minorities” [Report]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Baptist General Convention of Texas 1948-1951. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Mills, J. (1957, August 15). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 3, Segregation 1957. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Paul Quinn Students Serve on Morning Watch Programs. (1950, January 18). The Daily Lariat, p. 1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/23978/rec/57

Porter, C. S. (Ed.). (1948). The Round-Up. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-annl/id/24221/rec/1

Rhoads, J. J. (1950, September 12). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1948-1951. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Rothe, G. (1966, December 16). Baylor University Press Release, 12/16/1966. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tx-pr/id/18403/rec/3

Thelin, J. R. (2011). A History of American Higher Education (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

U.S. Supreme Court Outlaws on Negro Segregation Rules. (1950, June 6). The Daily Lariat, p. 1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/23768/rec/6

Wallace, J. D. (1957, Sept 25). [Letter to W. R. White]. Foy Valentine Papers: The Christian Life Commission- Work Files 1955-1987, Accession 2948, Box 88, Folder 2- Correspondence 1957. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, A. J. (1953a, April 14). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 3, Paul Quinn College 1953. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, A. J. (1953b, April 29). [Letter to W. R. White]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 3, Paul Quinn College 1953. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1950, May 17). [Letter to E. L. Martin]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1948-1951. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1951, February 9). [Letter to W. D. Varney]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1948-1951. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1953, May 20). [Statement of Support for Paul Quinn College]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 1, Bishop College 1953. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1955, November 1). [Letter to J. H. Bondeson]. W. R. White Papers: Personal Papers, Accession #BU/142, Box 10, Segregation 1955-1956. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (ca. 1956-1957). “Our Greatest Crisis” [typed article with handwritten draft]. W. R. White Papers: Personal Papers, Accession #BU/142, Box 2, White Articles 1956-1957. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

White, W. R. (1957, September 27). [Letter to B. Williams]. W. R. White Papers: Correspondence- Affiliations & Associations, Accession #BU/142, Box 3, Segregation 1957. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Appendix A

List of students of color from 1950 yearbook (Buchanan, 1950), as able to be identified by name, city of origin, and/or physical appearance, with page numbers for easy reference:

Asian and Asian American

Graduate students

David Chu (p. 32)- Shanghai, China

George Shan-Chang Hsieh (pp. 32-33)- Shanghai, China

Li Hisiu Albraham Sung (p. 34)- Shanghai, China

Rose Shiuan Ching Wang (p. 34)- Shanghai, China

Seniors

Irene Itokazu (p. 51)- Hawaii

W. Utokazu (p. 51)- Hawaii

Fred S. Kimura (p. 53)- Hawaii

Franklin K. S. Liu (p. 55)- Hong Kong

Calvin M. Shimotsu (p. 64)- San Benito, Texas

Juniors

Henry Y. Ikemodo (p. 82)- Escondido, Texas

Harold Itokazu (p. 82)- Hawaii

Mitsuko Noda (p. 86)- Hawaii

William M. Shinto (p. 89)- New Mexico

Anna Wang (p. 91)- Hong Kong

Sophomores

Jo Koon (p. 91)- Hawaii

First-Years

Samuel Liu (p. 115)- Hong Kong

Timoki Masaki (p. 116)- Hawaii

Middle Eastern Students

Juniors

Elijah Ovadiah (p. 87) – Jerusalem, Palestine

Fuad Musa Tawil (p. 91)[5] – Jerusalem, Palestine

Latino and Latin American Students

Seniors

Tony Campos (p. 40)- Baytown, Texas

Juan de la Cruz (p. 43)- Donna, Texas

Gonzalito Perez Reyes (p. 62)- Waco, Texas

Juniors

Joe Alvarez (p. 74)- Cameron, Texas

M. A. Sanchez (p. 88) – Grapeland, Texas

Sophomores

Jorge Cassis (p. 96)- Honduras

Abie Cazavos (p. 96)- Mexico

Frank Lopez Gonzalez (p. 98)- Beaumont, Texas

Jose Inez Mendoz (p. 101)- Brownsville, Texas

Alberto Trevino, Jr. (p. 105)- Escobas, Texas

First-Years

Jesus Ablos (p. 108)- Waco, Texas

Pedro L. Barba (p. 108), Waco, Texas

Mary Elizabeth de la Garza (p. 111)- Raymondville, Texas

Aseneth Orozco (p. 117)- San Antonio, Texas

Isidoro Plaza (p. 118)- Dilley, Texas

Law Students

Hector Sebastian Lopez (p. 130)- Oilton, Texas

Gil Garza (pp. 138-139)- Corpus Christi, Texas

[5] The 1950 yearbook misspells his name as “Twail” and lists him as being from “Jerusalem.” The 1951 yearbook spells his name correctly as “Tawil,” and identifies him as being from Jerusalem, Palestine. (Lyle, 1951, p. 55). The 1949 yearbook spells his name Tawil and lists his home as Hafar, Homa, Syria (Beckham, 1949, p. 105). For some reason, Tawil is not listed with his class in the 1948 yearbook, but a candid photo of him does appear on p. 107, which is listed under his name in the index on p. 409 (Porter, 1948).