The arrival of the year 1940 brought with it the recognition of Baylor University’s 95th birthday and the inception of a decade of institutional change. The Daily Lariat (1940 February 1), Baylor’s campus newspaper, published an article in celebration of this birthday occasion, entailing an excerpt which read:

Baylor is built on the gifts of her loyal friends and alumni. She has grown from a small one-building school at Independence to the largest Evangelical religious school in the world. It is now felt that Baylor is on the threshold of an even greater expansion than any of us have dreamed. Her alumni and friends will not fail her. (p. 2)

In a decade of great financial need, former students were called upon to pick up the burden of not only ensuring institutional stability, but engaging in the advancement and expansion of campus. This “threshold of an even greater expansion” would soon be crossed and alumni contributions would change radically in the 1940s, but not without campus administrators being forced to navigate through the tumultuous wake of World War II. This era was not the beginning of alumni contributions, as even in Baylor’s early history alumni were solicited and asked to advocate financially for their beloved school. For instance, Harvey Carroll, President of Alumni in 1869 pleaded with former students to contribute “fifty, one-hundred, twenty, or even five dollars, as [their] heart and circumstances may prompt” (Baylor Line, 1945 May, p. 11). Financial entreaties were not coined in the 1940s, but with the rise of Baylor’s image and prestige they were greatly sought after and utilized for the growing campus. Although it could be assumed university expansion would be nonexistent during war years, Baylor Alumni proved to be a functional source of funding, albeit grudgingly at times, for a few key projects on campus during the 1940s.

Baylor’s Ex-Student Association

The Baylor Ex-Student Association experienced great change during the 1940s. Created in 1859, the association had been in existence long before this decade, but it was in the ‘40s when things started to really take off. In 1942 the Baylor Ex-Students Association became legally incorporated, and a few years later it would become a separate entity from the university. The Baylor Century, the Association’s alumni magazine at the time, was revamped and retitled the Baylor Line in 1946.

Former students would see a shift in the Ex-Student Association to a more proactive agenda in operations, especially soliciting donations. The campus newspaper highlighted the assertive shift in alumni connections and fundraising, and reinforced the mission given to alumni to aid in expanding campus. “The ex-students, numbering 40,000, have in ‘The Baylor Line’ an outlet through which their concerted efforts may be used in accomplishing their aims of rebuilding and enlarging Baylor.” (The Baylor Lariat, 1946 October 25, p. 2). In one of its first issues, Jack Dillard announced in the Baylor Line that “Baylor’s Ex-Student Association has launched an aggressive, far-reaching program to enlarge and strengthen itself” (Baylor Line, 1946 October, p. 2). It is clear to see the tactics used by the Ex-Student Association through the Baylor Line to gain access to more alumni generated finances, especially towards building projects on campus.

The Association’s Executive Secretary Jack Dillard recognized the difficulty of war time in attempting to maintain the daily functions of this alumni association. He wrote in a volume of the Baylor Line “We know our mailing list is in bad shape. How else could it be with all the displacement of war-time?” (Baylor Line, 1947 January, p. 4). He also acknowledged the rising interest in the university, with the corresponding need for financial support through alumni.

Dillard observed that many Ex-Students were withholding their contributions to the university, but he saw a slight change in the 1940s, which showed many beginning to acknowledge the need for necessary funds to expand campus. Through the Baylor Century and later the Baylor Line, Dillard emphasized the need to capitalize on this shared interest to further expand the Baylor image. He mentions that “Baylor exes over State and Nation are catching fire. There appears to be more interest on part of Baylor exes in their Alma Mater than at any time in history” (Baylor Line, 1947 March, p. 13). He took notice of this changing time and the importance alumni would continue to play in campus expansion.

The State of the Institution

Baylor’s efforts to fling her green and gold afar were met with increasing struggles to acquire the necessary resources for this mission. In the 1940s Baylor University was a high-functioning institution which would celebrate its centennial year of existence in mid-decade (1945) and was growing into a mature establishment of learning. With the involvement in World War II in the early years of the decade, Baylor’s administration could not know the ways this global crisis would affect operations on the home front. But even as Axis powers abroad attempted to wreak havoc on the world, Baylor’s campus made plans for growth. Some of the biggest courses of action for Baylor’s future involved campus expansion and improvement, a challenging goal which her alumni would attempt to assist with.

However, World War II played a large role in former student’s inability to give back. Not only did society need to be economically frugal, but the lack of student presence due to overseas service was evident in the lack of financial support. Many students, both current and former at the time, adhered to the call of service during the decade. There was thought to be a national “reduction of about 50 percent in the male student body of the colleges” (Daily Lariat, 1950 October 11, p. 1) during the war. Not only were there less students on campus, who would soon become alumni, but the war limited the amount of alumni which could be called on for financial donations to the university. Additionally, wartime casualties had an unfortunate impact on the number of alumni. The Baylor Century magazine acknowledged this concern in noting “War continues to exact its inevitable toll on former Baylor students” (1944 October, p. 10). Baylor administrators also raised alarm given the draft regulations during war time, with many noting that “along with the draft [are] increased operating costs due to the present inflationary spiral, decreasing enrollments stemming from attractive opportunities offered by war industries, and increased taxes and a decrease in gifts to the university” (The Daily Lariat, 1950 October 11, p. 1). The combination of these factors during and immediately following the second World War would test the resilience of Baylor’s administration, fundraisers, students, and alumni.

There were many important developments on campus in the 1940s, but the three largest which called for alumni assistance were completing construction of the Union building, launching construction for the Browning Library, and making an improvement to the school’s endowment. A fourth major campus project seeking Baylor alumni support was the construction of a new football stadium, which started taking shape around the end of the decade. Attaining necessary funds for these sizeable campus projects was not easy, especially in a time of war, but Baylor alumni were able to contribute enough collectively to help the university not only stay afloat during the 1940s, but prosper as well.

Finishing the Union Building

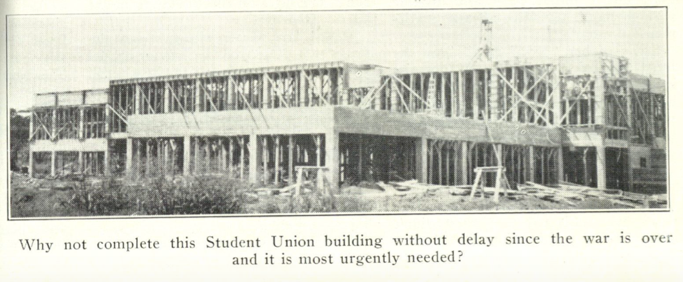

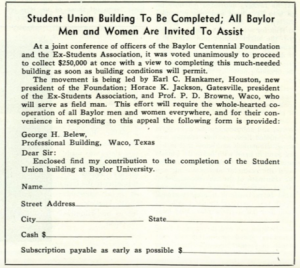

In 1935 the idea of the Union was envisioned by Dr. K. H. Aynesworth, which led to the formation of the Centennial foundation comprised of Baylor ex-students. This group of alumni pledged to give $80,000 for the building “in $5 a year individual gifts until the centennial year” (The Baylor Lariat, 1946 October 25). During the period of Union building fundraising, “Ex-Baylorites urged their fellow alumni to pay pledges, to enlarge pledges, to get friends to help” (The Baylor Lariat, 1946 October 25). Unfortunately, building was slowed and construction did not go exactly as campus officials had planned.

The university’s administration had “planned to have an adequate Union building ready for use by or before the Centennial year. Large gifts and small were coming from month to month; the building was designed and being constructed; then war came and the Union building half complete had to wait” (Baylor Century, 1944 October, p. 6).

It is clear to see how big of an impact the war had on campus. Although money for the Union project continued to come in during these years, it was in much smaller amounts. However, alumni foundation officers were “confident that the building [could] be completed very soon after the war [was] over” (Baylor Century, 1944 October, p. 6). University President Pat M. Neff announced that the upsetting standstill in building would soon resume in 1946, after this necessary break during the war years (The Baylor Lariat, 1946 January, p. 1). The unfinished frame of the building on campus stood for four years as a reminder of the “lack of funds and war-time building conditions” (The Baylor Lariat, 1946 January, p. 1).

President Neff’s announcement was met with enthusiasm as the Union was a building hailed as essential to campus. Even Neff himself noted:

As we face our responsibilities’ to the throngs of students clamoring for admission to Baylor, to our veterans returning to complete their education and to our homecoming ex-students, we realize that the Union building is now the most needed building on the campus. (The Baylor Lariat, 1946 January, p. 1)

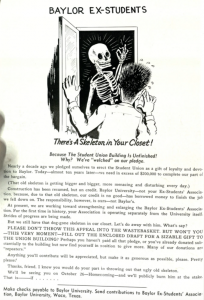

However, the reaction to Neff’s declaration was an eagerness from students for swift completion. The Union building was a slow project, and multiple announcements of its completion date had created some angst within students. “Announcement that the Student Union Building would be completed by such-and-such a date had been made on numerous occasions – so many times that students and ex-students alike had shrugged their shoulders and said: ‘I’ve heard that before’” (Baylor Line, 1947 April, p. 5).

Campus administrators could clearly see the need for alumni to give more for expansion, but were also grateful for any funds they could acquire. Lily Russell, the first Dean of the Union Building appointed shortly before the building’s conception, realized this struggling nature of alumni support. She documented a donation from one former student, stating “I am enclosing a check for $1.00 from Mrs. J. A. Thompson of Houston to apply on the Union Building” (Russell, L., 1942, February 21, Check processed for Union Building). Though most alumni were not able to give contributions to the university in ways that some powerful (non-alumni) donors did, such as Marrs McLean or Herbert Kokernot, who gave millions of dollars, it appeared, by example of a mere one-dollar check, that they were giving what they could in these hard times (D.K. “Dock” Martin Papers, Baylor Finances). Raymond Dillard was elected President of the Ex-Student Association in 1945 and shortly after posed the question to alumni why the building project was not finished. The war was over and R. Dillard expected the Baylor exes to come through on this long-promised necessity to campus. In a 1946 issue of Baylor Line, aggressive marketing tactics were being seen to speed up the final period of fundraising. Baylor alumni did not want to deal with this so called “skeleton in their closet” by failing to fulfill their goal of funding the Union (Baylor Line, October 1946, p. 24).

Through an extended waiting period of war time delays and financial struggle, the alumni, in conjunction with other donors, were able to contribute necessary funds to complete the construction. They did their part and the Student Union Building was finally opened in the fall of 1947. The completed project was loved by many students, but also by faculty. Charles Johnson writes in the Baylor Line about the adornment of the new Union. One Baylor professor asked “How did we get along without this building?” “Well,” another replied “We have known for years that this kind of building would do a lot for Baylor but we had no idea that it would be as great an influence for high intellectual attainment as we are all realizing now.” (Baylor Line, 1950 May-June, p. 14).

The Union was a triumph on campus and the alumni could proudly be credited with financial assistance during the process. Lily Russell noted that “ex-students…have made larger and larger use of the facilities of the building and it would be possible to fill the whole schedule with their activities” (Russell, L., 1949, May 16, Address to the Union board). Soon the Ex-Student Association would relocate its headquarters in the Union, but for the time being, most were pleased it was simply completed.

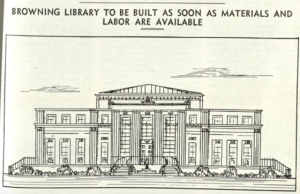

Financing the Browning Building

The Browning building, which would later be renamed the Armstrong Browning Library, houses the largest collection of memorabilia relating to the Victorian poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Dr. A. J. Armstrong founded the library and would play an integral part in its design and function. Baylor President Pat Neff emphasized the importance of the Browning building and offered $100,000 of the university’s money towards its completion. He then challenged Dr. Armstrong to fundraise the remaining amount. Armstrong would answer this call of responsibility, but as with most fundraising attempts during the decade, would feel the pressure and sluggishness of a post-war economy. The Baylor Century noted how the Browning building “during the Centennial year [has] been delayed,” but will “be erected soon after the war” (Baylor Century, Oct 1944, p. 6).

Jack Dillard, in a letter to Dr. Armstrong, approved of the fundraising tactics Armstrong was utilizing for his project through alumni aid. Seeking alumni support would continue to be an integral component of completing the mission to bring the building to life. Dillard said in the letter “You have done, and continue to do a most outstanding job in campaigning for funds for the building” (Dillard, J., 1948, December 9, Letter to Dr. A. J. Armstrong). Dr. Armstrong wrote a short article in the January 1948 issue of the Baylor Line addressing the significance of ex-students and their financial support. Titled “I See the Dawn,” a section of his article stated “We have tried to do things that are worth-while but are far beyond our financial income. Baylor has had financiers at the helm to steer it through a century on the income thoroughly inadequate” (Baylor Line, 1948 January, p. 24).

Dr. Armstrong recognized the impact of the war on Baylor’s financial foundation and how the university had managed to overcome this adversity to continue making progress. He voiced that many of the current campus expansion campaigns, which were envisioned in the previous decade, such as the Student Union, were finding difficulty in being realized. Additionally, Dr. Armstrong mentioned the generosity of alumni in donating towards the Browning Library, among other projects, as an integral feature of campus expansion, “Some have contributed large sums and are proud of it, and some have contributed smaller sums and have felt sorry that they could not give more” (Baylor Line, 1948 January, p. 29).

Dr. Armstrong knew that ex-students were doing what they could with what they had. He tells the story of difficult financial years being overcome with the help of a strong alumni body. Towards the end of the article he highlighted that ex-students gave nearly $200,000 for the new library. He concluded by stating, “considering the modest financial rating of the student who attends Baylor, this is a magnificent showing. Baylor University has great reason to be proud of its children. HAIL TO BAYLOR’S ALUMNI AND EX-STUDENTS!!!” (Baylor Line, 1948 January, p. 29). Much of the splendor one can see in the Browning building came from alumni donations. Two Baylor alumni, former students of Armstrong, gave $15,000 for the marble staircase in the building, and another ex gave $5,000 for stained glass windows (Baylor Line, Dec 1946, p. 25). After alumni and friends of Baylor were able to contribute the necessary funds to start building, ground was broken on the project on May 7, 1948. It was not until the end of 1951, though, that the building was finally available for use.

Improving the Baylor Endowment

When Pat Neff was reigning president at Baylor he developed a $10,000,000 endowment plan to grow the university, which was approved by the Board of Trustees. This operation would no doubt need the help of alumni. But when William R. White assumed the position of president at the beginning of 1948, he wanted to push the expansion limits of Baylor even further. In Dr. White’s inauguration speech, he called for unprecedented physical growth of Baylor (Baylor Line, 1948 April, p. 3). He aimed to make big changes for the betterment of campus, and one of the first items on his list was improving the endowment. In an interview with the Baylor Line, Dr. White mentioned that “Within the next 10 years Baylor’s endowment should be brought to $25,000,000” (Baylor Line, 1948 April, p. 24). This mission of growth would be one that White looked toward alumni to help fulfill.

President White described Baylor ex-students as “one of Baylor’s greatest assets and a potent force” (Baylor Line, 1948 March, p. 6). White recognized the power and resources that alumni can bring to a school to which they feel strongly connected. Although White notes Baylor’s ex-students have “made rapid strides of progress during the past several years,” he charges them with going further and predicts “an even greater future” (Baylor Line, 1948 March, p. 6). White wanted the Association to keep a strong partnership with Baylor, and hoped alumni would continue to help financially through the future years. The endowment was a great place for alumni to give for the future, and White said the “Association will have my hearty support” for planning the road ahead (Baylor Line, 1948 March, p. 6). White also noted how he wanted the opportunity to meet many more former students by doing some traveling across the state during alumni fundraising. He wanted to get acquainted with former students as the new university president, but was clear that he sees alumni as necessary supporters in saying “I’m going out after money” (Baylor Line, 1948 March, p. 6).

White wanted to seek aid from alumni to not only raise the endowment and finances for other campus projects, but to address the staggering debt Baylor was in. In less than a year, with help from ex-students, Baylor’s debt was reduced from $900,000 to $50,000. That was a significant improvement, which the Baylor Line addressed by commenting “1948 was the best financial year in [Baylor] history” (Baylor Line, 1949 May-June, p. 7). Pat Murphy, editor of the Daily Lariat noticed about campus that:

Everything is here now. New buildings are going up and being opened. Everywhere there is expansion, growth, an increase of modern facilities and equipment. Baylor is not only a tradition filled, historic old university, but is rapidly assuming the proportions of a brand- new one.” (Baylor Line,1947 October, p. 12).

However, one more project would help define the appropriations of alumni support in the 1940s: a new football stadium.

Financing a New Football Stadium

Jack Dillard, executive secretary of the Ex-Students Association, highlighted the agenda of the Association by declaring that the group is focused on “advancing Baylor ‘spiritually, scholastically and athletically’” (The Daily Lariat, 1949 February 2, p. 1). A. Grady Yates, the new president of the Ex-Students Association, in his first address to alumni via The Baylor Line, remarked that the new stadium is the biggest challenge to overcome right now. Baylor was in the era of gaining sharp competitiveness in athletics and needed the facilities to declare and prove their belonging. Yates tells alumni, “We appeal to you to do your part…financially” (Baylor Line, 1949 July-August, p. 15).

With the idea and progress for location and construction underway to build a new football stadium, alumni were promised first choice of tickets. But in order to get funding secured from these ex-students, Baylor decided to create a plan to sell seats in the form of season tickets. This would allow the institution to collect up front and would promise enthusiastic alumni a seat on game day. Yates stated “You are going to disappoint yourself if you do not have a part in building this stadium. You are going to be disappointed and unhappy time and again, if you do not protect yourself and family for seats in the choice reserved sections. Stop, look and think how easy it is for you to finance the purchase of seat options!” (Baylor Line, 1949 September-October, p. 13). In a very aggressive way we can see the plea from Yates to invest in Baylor.

Yates continues to encourage the purchase of available seat options, which include “Class-A seats at $100 each; Class-B Seat at $50 each; Education Bonds of $1000.00 each, bearing 3% compounded interest, good for tuition only; and Investment Bonds of $500.00 and $1000.00 each, with interest at 3% payable annually.” (Baylor Line, 1949 September-October, p. 13). In addition to football seat options, Yates highlights other ways to contribute to Baylor, through investment bonds, which might have also been applied to the endowment, and education bonds, where the principle and interest could be later used for tuition. He certainly hits at the necessity of purchasing seats or other donation options, emphasizing the importance of viewing Baylor football games and how one would be extremely disappointed if he were to miss out on the opportunity. George Sauer, Baylor head coach and athletic director in 1949, would make a tour of Baylor Ex-Student clubs throughout Texas to promote this new campus feature and appeal for donations from alumni for the project (The Daily Lariat 1950 February, p. 1).

Alumni and other Baylor Bear football fans contributed enough monetary funds to get the project underway. Ground was broken in May of 1949 and construction began to further expand Baylor and her image in the community, state, and nation. The new stadium was greatly anticipated, so much so that President White moved “Alumni Day” to the fall to create more interest for alumni (The Daily Lariat 1950 May 17, p. 1). The stadium was opened on September 29th and the Bears had their first game the follow day against the University of Houston. The construction of the new stadium was yet another project Baylor alumni helped fund during the 1940s.

Conclusion

Alumni have played an integral part in financing the expansion of Baylor University in the 1940s. Through the unique, and sometimes aggressive strategies of intentional fundraising, her alumni helped Baylor cross the threshold into an era of expansion greater than many had envisioned. Throughout the decade alumni were called upon again and again to give back to their alma mater. Although the acquisition of funds was not always smooth sailing, and while it occasionally took some deliberate aggressive marketing to get donations, alumni played an important role in campus growth during this decade.

Making good their promise to fund the student union, helping finance the Browning Library, contributing to the much needed endowment enlargement, and serving as a key source of income for the construction of a new football stadium, alumni, in the aggregate, did their part to give back. Their assistance, though sometimes squeezed out through multiple solicitations, contributed to a larger and more recognized Baylor. Through the challenging years of World War II and difficult navigation of a post-war economy, Baylor excelled in the 1940s and reached their goal of large campus expansion, thanks in part to generous ex-students.

References

Armstrong, A. J. (1948) “I see the dawn” Hail to Baylor’s ex-students. The Baylor Line, 10(1), 24; 29.

Beene, L. F. (1946 October 25). “Not This Homecoming, But Union to Be Ready in ‘47.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/22374/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1946) Ex-Students’ association launches enlargement program. The Baylor Line, 9(1), 2, 24.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1946) Cornerstone ceremony for Browning building scheduled for May 7, 1947. The Baylor Line, 9(2), 25.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1947) Dear Ex: (A letter to Ex-Students). The Baylor Line, 9(3), 4.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1947) Dear Ex: (A letter to Ex-Students). The Baylor Line, 9(4), 13.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1947) Baylor’s spring term enrollment highest in history of school; building expansion program accelerated. The Baylor Line, 9(5), 5.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1947) Baylor’s wide-spread growth and expansion reflected as students return for new year. The Baylor Line, 9(8), 12.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1948) Ex-Students of Baylor great asset to university and potent force, Dr. W. R. White emphasizes. The Baylor Line, 10(2), 6.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1948) Dr. White becomes Baylor’s ninth president; calls for unprecedented physical growth of all Baylor units; pledges boost in academic standing. The Baylor Line, 10(3), 3.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1948) New football stadium top project in Dr. White’s program for Baylor; $25,000,000 endowment needed, says new president, who is East Texas’ ‘Man of the Month.’ The Baylor Line, 10(3), 24.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1949) Enrollment, debt problems settled; Baylor moves into open field, heads for touchdown. The Baylor Line, 11(3), 7.

Dillard, J. (1948 December 9). [Letter to Dr. A. J. Armstrong]. Pat M Neff Collection (Box #151, Folder #2). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Dillard, J. (Ed.). (1949) President Yate’s Challenge……. The Baylor Line, 11(4), 15.

Dudley, W. (Ed.). (1946 January 26). “Work to be Resumed on Union Building.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/34380/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Gailey, A. (Ed.). (1940 February 1). “Baylor – A Glorious Past and Future.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/31204/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Hulme, L., Murphy, P., Neal, T. (Eds.). (1946 October 25). “Baylor Throws Doors Open to Ex-Students.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/22374/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Johnson, C. D. (Ed.). (1944) Student Union building campaign form. The Baylor Century, 7(1), 3.

Johnson, C. D. (Ed.). (1944) The centennial year. The Baylor Century, 7(1), 6.

Johnson, C. D. (Ed.). (1944) War continues to take heavy toll. The Baylor Century, 7(1), 10.

Johnson, C. D. (Ed.). (1945). Centennial year reveals prized alumni letter. The Baylor Century, 8(3), 11.

Johnson, C. D. (Ed.). (1945). Union photo – incomplete construction. The Baylor Century, 8(1), 3.

Johnson, C. D. (1950) This is Baylor. The Baylor Line, 12(3), 14.

Marsh, H. (Ed.). (1949 February 2). “White Enumerates Baylor Virtues in Founders’ Day Celebration.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/23676/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Martin, D. K. (1946 October 12). [Letter to Dr. E. G. Gregory]. D.K. “Dock” Martin Papers #222 Baylor Finances (Box #1, Folder #9). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Martin, D. K. (1948 April 30). [Letter to Ray Dudley]. D.K. “Dock” Martin Papers #222 Baylor Finances (Box #1, Folder #10). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Russell, L. (1942 February 21). [Passing forward of monies to Baylor Finance Committee]. Dean of the Union Building (Lily Russell) papers (Box #1, Folder #12). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Russell, L. (1949 May 16). [Address to Union Building Board]. Dean of the Union Building (Lily Russell) papers (Box #1, Folder #20). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Smith, W. (Ed.). (1950 October 11). “BU Officials Express Alarm at Draft Losses.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/24955/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Taylor, E. (Ed.). (1950 February 14). “Kultgen Named Stadium Head at Meeting.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/23800/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Taylor, E. (Ed.). (1950 May 17). “BU Alumni To Gather in Waco Sept. 29 For Stadium Opening.” The Daily Lariat. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/23832/rec/1 The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Yates, A. G. (1949) The Baylor stadium. The Baylor Line, 11(5), 13.