By Alejandra Mendoza-Muñoz

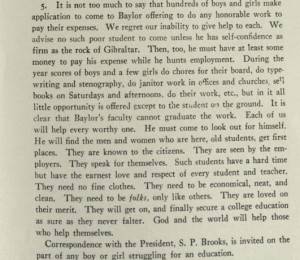

Access to higher education from 1900 to 1920 was not readily available for financially disadvantaged students. The most direct way to have access to Baylor during this time was to graduate from an affiliated high school; these students received automatic admission into the university. The real problem was not academic qualification, however, it was ability to pay tuition. A student who could not afford to pay faced restricted access to a Baylor education. The Baylor Bulletin from 1909-1910, printed for student use, stated:

It is not too much to say that hundreds of boys and girls make application to come to Baylor offering to do any honorable work to pay their expenses. We regret our inability to give help to each. We advise no poor student to come unless he has self-confidence as firm as the rock of Gibraltar. Then too, he must have at least some money to pay for his expense while he hunts employment…Each of us will help every worthy one. He must come to look out for himself…God and the world will help those who help themselves (Baylor Bulletin, 1909-1910, p. 9).

Baylor attempted to discourage poor students from attending if they did not have money to pay for their expenses because it had limited resources and could not afford to help every financially needy student. Despite the struggle to provide for every student, historical records reveal that Baylor accommodated financially needy students by placing a major emphasis on ministerial scholarships, accepting donations to create more scholarship opportunities, providing a venue for employment, and establishing the department of correspondence.

Ministerial Aid

Baylor prioritized financial accommodations to students going into the ministry and ensured these students received the financial aid they needed. From the start of the century, Baylor records show a consistent desire to invest in ministerial students. In 1904, for instance, The Board of Trustees, fundraised money to help deserving young ministers to pay their “board, house rent, or other necessary expenses beyond their own ability to meet while in school” (Baylor Bulletin, 1904-1905, p.79). The fund was not to be viewed as charity but instead as an investment on the student. Furthermore, the fund did not grant full tuition to the students; it aided in their expenses. Students were still responsible for paying entrance fees with matriculation. Minister’s children on the other hand, had free tuition in the Senior Academy, College, and Theological Departments provided they “do five hours or less of clerical or library work per week” (Baylor Bulletin, 1904-1905, p.80).

Five years later, the Report of the President and Trustees provided helpful information about the improvements in the financial support of students in the ministry. The report urged any ministerial students needing help to correspond with Prof. J.B. Tidwell who was in charge of distributing funds fundraised for this purpose (Baylor Bulletin, 1909-1910, p.8). Appointing a professional to help financially needy students in the ministry emphasizes Baylor’s desire to help these students and reveals the young preacher’s importance to the institution. Baylor furthered its efforts to provide for ministerial students by securing full tuition for them. In a letter from President Brooks to the Board of Trustees, he wrote, “For the year ending June 30, 1912, Baylor had given away in tuition and monitorial service $13,152.45. Nearly all of this amount was for the free tuition of preachers and their wives, or the sons and daughters of preachers.” This was possible through Baylor’s request of church contributions, “The University has no funds with which to help such indigent worthy students but now calls on the churches for contributions” (Baylor Bulletin, 1909-1910, p.77). By 1910, students in the ministry received full tuition and only had to pay fees. Baylor’s efforts continued to improve in 1920 when they assigned Rev. J.B. Tidwell, formally managing the distribution of funds, to aid in fundraising from churches (Baylor Bulletin, 1920). Although Baylor could not provide financial aid to every needy student, it focused its efforts on granting help to ministerial students.

Non-ministerial aid

Baylor’s emphasis on ministerial aid did not dismiss the need to accommodate other students facing financial difficulties. Usually motivated by outside influences, donors encouraged financial accommodations that aligned to Baylor’s needs of the time. Donors often wrote to the President and the Board of Trustees asking about a “net amount of money that would be acceptable…for the permanent Endowment of a Scholarship” (Brooks, 1905). The type of scholarships offered was considerably dependent on the availability of outside donations. As a result, Baylor created financial aid opportunities for top graduating seniors, women, and members of specific societies.

Baylor attempted to attract top students with merit base scholarships the way other state universities were doing. In a letter, President Brooks wrote to Mr. Murrell, a donor:“You know that the University of Texas gives a scholarship to the highest honor graduate of all of the high schools of the State. Baylor is also attempting to do this, but we have not Endowment enough to make it a safe business proposition” (Brooks, 1918). A few months prior to the letter, the Lariat published a list of scholarships, one of which was “given each year to the highest honor graduate of each of our correlated schools” in exchange for “clerical help in library, laboratory, or elsewhere, at the discretion of the president of the University” (Armstrong, July 18, 1918). In this case, accommodating top high school students with a merit-based scholarship rested with the President, who actively attempted to build a fund for the scholarship by writing to outside donors.

At the start of the century, in 1904 and 1905, scholarships were usually granted to members of specific societies who won oratory contests and graduates of Baylor seeking graduate work or students in the ministry. By 1909, Baylor had kept the main scholarships in this area, some of which included: The Rufus C. Burleson Fellowship in English for graduate students seeking graduate work in the English Department, The Philomathesian Scholarship awarded annually to the member of that society who wins first place in an oratory contest, The Erisophian Scholarship awarded annually to a member of that society who wins first place in an oratory contest, and The Calliopean Scholarship awarded “similar in purpose and valuation to the above mentioned” (Baylor Bulletin, 1909-1910, p. 73). Baylor also began implementing scholarships such as The Bennett Scholarship given to “a worthy but needy young lady,” and the Student Help Fund “lent to worthy students while pursing their studies in Baylor” (Baylor Bulletin, 1909-1910, p. 73). With the addition of scholarships for women and non-ministry students, both donors and the university broadened financial assistance to students beyond those in the ministry. Approximately eight years later, the Lariat on July 18, 1918 said, “There is no reason why a student should not go to college. Read this list of scholarships. Write for full particulars.” The list of scholarships included a few new options; there were more Literary Society and field specific scholarships, demonstrating further progress of financial accommodations to non-ministerial students.

Lastly, a report of the President and Trustees in 1909 provides helpful information about additional financial aid opportunities to women. The report advised girls paying their own way through college by working or girls whose parents were not able to pay board should write to Mrs. P.W. Walton who was in charge of the Girls’ Home, a home for indigent girls (Baylor Bulletin, 1909-1910, p. 8). Establishing a home specifically for poor girls not only reveals Baylor’s concern to provide access for women, but it shows both Baylor and donors valued women education at the time. In the same year Baylor advised no poor student to attend, it encouraged poor women to write to Mrs. P.W. Walton. The contrasting evidence provides context to the environmental factors Baylor faced at the time: it did not have the endowment to help everyone but it supported students for whom donors encouraged financial accommodations.

Employment

Providing a venue for employment was another necessary accommodation to provide access for students with financial needs. Since few needy students were able to afford the expense of a higher education simply by the means of a scholarship, securing employment was a crucial additional step. In the early 1900s, a regular advertisement in the Lariat asked students to sign up to sell Harp of Life, a subscription book by Dr. Lofton. “About forty young men are devoting the vacation months to the sale of ‘Harp of Life’ and a good many of them have already made fine records, though they started out absolutely without previous experience. We still have some fine territory and want all agents we can get” (Crouch, August 9, 1902). The advertisement was printed for almost an entire semester indicating either a high turn over rate for the sales position or students simply did not find the job opportunity a good use of their time.

The need for an employment bureau became more evident in the next few years as students earned their entire way through college. The Lariat highlighted one student in this situation, “I earned my way thru college corresponding for newspapers and magazines. Any intelligent man or woman can do the same by following my method” (Link, January 9, 1909). That same year, the Lariat published a report from the committee on employment for students at Columbia University, New York recommending the idea of an employment bureau: “Last year this committee found employment for seven hundred twenty-two students in all sorts of places from janitor work to tutoring…there is an excellent opportunity for such work in Baylor and it will only be a matter of a short time until someone will start it” (Link, January 9, 1909). Ten years later, the Lariat explained that Baylor had the largest total enrollment of any previous year, and it expected a large number of students would want to work to help pay part or all of their expenses. By then, the employment bureau had been established. The Lariat states:

In every great college or university there is a far larger percentage of men and women who earn their entire expenses than is generally supposed. Harvard is always spoken of as the rich man’s school and yet it is officially announced that more than half of the young men earn every cent of their expenses (Anonymous, August 14, 1919).

By the year 1919, Baylor had adapted the ivy leagues’ employment bureau idea. Furthermore, Baylor attempted to improve its employment bureau processes: “For several years the employment bureau for students has been organized and has done most acceptable. This year in connection with the bureau the business club committee is doing valuable work toward getting prospects students located in some kind of work” (Anonymous, August 14, 1919). Baylor offered support in the establishment of the employment bureau and attempted to improve the process as an adjustment to help those who must help themselves get through college.

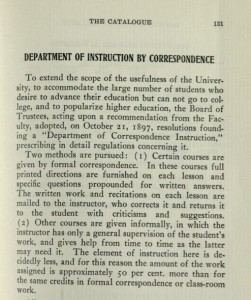

Department of Instruction by Correspondence

Besides the scholarships and employment opportunities available to students, Baylor also offered a Department of Instruction by Correspondence from which students were able to take classes without having to attend college, the equivalent to online courses today. The purpose of the department was “To extend the scope of the usefulness of the University, to accommodate the large number of students who desire to advance their education but can not go to college, and to popularize higher education” (Baylor Bulletin, 1904-1905, p. 131). All students who were to enroll in these courses were considered official students of the university and were to receive credit toward a degree for their work. Full lessons were mailed to the students with written instructions and assignments to be mailed back to the professor when completed. Because the instruction was less and a student was not in a classroom, the fees for these courses were less than the tuition fees incurred when attending college (Baylor Bulletin, 1904-1905, p. 131). Correspondence study continued all throughout the 1920s since Baylor recognized the need to meet student individual needs. However, the institution also encouraged students to attend the university by offering a scholarship, “A student making a grade of B in four majors of correspondence work will be given a scholarship for a quarter’s residence work in any quarter except the summer. This scholarship exempts from tuition only” (Baylor Bulletin, 1920, p. 55). Providing this service indicates another way in which Baylor attempted to work with the struggles of the time and continued to provide some access to higher education to financially needy students who wanted it and deserved it.

Conclusion

Baylor’s means of providing access to higher education through financial aid continually and progressively improved over the years. Within only a twenty-year span, it is obvious that the institution faced struggles in providing financial help for obtaining a higher education yet continued to find ways in which to provide for these needs through scholarships, employment bureaus, and the Department of Instruction by Correspondence. Though the financial aid opportunities offered to provide access may not have always been enough to provide for all of the students in need, the opportunities seemed to improve over the years. Baylor was able to adapt and implement initiatives in response to the needs of the time. For instance, with the growth in enrollment, many students needed financial help to access a Baylor education resulting in the establishment of an employment bureau. However, the extent to which students took advantage of these opportunities is unclear: “During the past two years there were more jobs open to men and women in Baylor than there were applicants to fill them” (Anonymous, August 14, 1919). Although Baylor progressively broadened the types of financial support it offered, the responsibility of paying for a higher education always remained with the student.

References

Anonymous. (1919, August 14). Self Help Among Students. The Lariat. p.1. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/5036/rec/1

Armstrong, A.J. (1918, July 18). An evidence of superiority of denominational college. The Lariat. p.2. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/5483/rec/1

Brooks, S.P. (1905). [Letter from President Brooks to the President and Trustees of Baylor University, Board of Trustees Minutes]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Brooks (Samuel Palmer) Folder #299 “Baylor University Records: Financial Affairs- Scholarships, “ Waco, TX.

Brooks, S.P (1918, December 4). [Letter from Samuel Palmer Brooks to J.F. Murrell]. The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (Brooks (Samuel Palmer) Folder #299 “Baylor University Records: Financial Affairs – Scholarships,” Waco, TX.

BU Records. Board of Trustees, BU/0050, Box #12, Folder #73, The Texas Collection, Baylor University

BU Records. Board of Trustees, BU/0050, Box #13, Folder #74, The Texas Collection, Baylor University

Crouch, A.B. (1902, August 9). “Harp of Life” Advertisement. The Lariat. p.3. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/3037/rec/1

Link, H. (1909, January 9). Kenneth D. Steere Advertisement .The Lariat. p.3. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/4064/rec/1

The Baylor Bulletin. (1904-1905). The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (LD346B858x1904-05 v. 8), Waco, TX: Baylor University.

The Baylor Bulletin. (1909-1910). The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (LD346B858x1909-10 v. 13), Waco, TX: Baylor University.

The Baylor Bulletin. (1913-1914). The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (LD346B858x 1913-14 v. 17), Waco, TX: Baylor University.

The Baylor Bulletin. (1920). The Texas Collection at Carroll Library (LD346B458x 1920 v. 23), Waco, TX: Baylor University.