by Gabriela Olaguibel

From their founding, institutions of higher education respond to their surrounding communities. After all, colleges were often created by their communities, which also contributed their youth to the make-up of the majority of the student body. Because of the nature of this relationship, colleges respond to societal demands in many ways. One such response can be seen in the area of curriculum. As much as colleges are conservative institutions resistant to change, attracting the necessary enrollment for said curriculum proves to be a key element in the shaping of it. The twentieth century witnessed a decrease in popularity of the classical languages in society as a whole, along with a rise in demand for modern languages, shaping curriculum accordingly. At Baylor University, great development takes place in the Spanish department, triggered by this increased demand for it during this decade.

At Baylor University, the demand for Spanish especially after WWI resulted in the fast growth and development of the Spanish Department in the decade of 1920 to 1930. This growth can be seen through major changes and additions in the content and number of Spanish courses offered, the emergence of new programs, and the arrival of new faculty. The change in demand of classical to modern languages provided the context and space for the Spanish Department at Baylor to develop and take off during this decade.

Decrease in Classical Languages at Baylor

It is impossible to address the growth of modern languages at Baylor without considering the decrease that the classical languages underwent as well. The decade prior had witnessed the debate over the Latin requirement, seen especially between Latin Professor Downer and French Professor Brisoe. The Bulletin of 1915-16 begins with Downer’s piece: “A Plea for Latin” (Baylor Bulletin 1915-16, p.3). One of Briscoe’s famous remarks on the matter, probably not the only one sharing this sentiment, states that he sees “no occasion for studying a language which is already dead,” as found in a Lariat of 1918 (Baylor Lariat, 1918).

Despite Downer’s attempts, the Latin requirement was dropped from the core curriculum in 1918, and demand for the language was steadily decreased approaching the decade of 1920 to 1930. This dynamic paints the background of the context in which the modern language curriculum, especially that of Spanish, took off at Baylor during this decade.

Modern Languages after WWI

Spanish professor Andrés Sendón mentions in an oral interview in 1971 that he was invited to teach Spanish in 1919 by President Brooks because of the increase in demand for Spanish after the First World War. This demand also sparked the beginning of the Spanish Club, which Sendón was greatly involved in (Walker 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón, p.7). In the previous decade, while the classical languages experienced decline in demand, seen through the dropped Latin requirement along with reduced Latin course offered, the modern languages of Spanish and French experienced the opposite effect, with increased course offerings.

In the Baylor Bulletin of 1910, while every other language and field of study has its own heading, “French and Spanish” are found together as one, with only three courses of each offered (Bulletin 1909-10, p.38). By 1920, demand for these languages had increased to where Spanish alone lists twenty courses offered (“Spanish” and “French” finally serving as separate headings) (Bulletin 1920, pp.106-107).

President Brooks and the Spanish Faculty

The increased demand for Spanish after WWI that Sendón mentions is further evidenced in President Brooks’ selectivity in his hiring process of Spanish faculty. Indeed, demand for Spanish grew during this time; however, there were also professors actively seeking employment in the area of Spanish at Baylor. Two pieces of correspondence addressed to President Brooks show interest on the part of these individuals to teach Spanish at Baylor, from O.S. Garnett and C. M. Montgomery. One of these is actually a second inquiry alluding to a former letter in which President Brooks communicates a recently secured position for the Spanish department. Montgomery writes further “I noticed that your school has a very large enrollment this year and thought you might need another man for next year” (Brooks, S.P., Montgomery to Brooks, November 13, 1919). Despite the increase in student demand Montgomery notes and the evidenced availability of interested Spanish professors, Brooks chose not hire those directly seeking employment at Baylor, but rather personally sought out professors elsewhere.

In this same year of 1919 Brooks contacted two individuals that would later become two of the main professors in the Spanish Department at Baylor. By 1920 the Spanish Department had three full-time professors: Professor Buldain, who was head of the department beginning the decade (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón). Professor Sendón, probably the youngest of the three, and Professor Sparkman, who had been teaching at Baylor since 1913 (Sparkman Subject File).

President Brooks may have considered these individuals to possess certain characteristics that not every person seeking to teach Spanish at Baylor did. Especially considering Sendón and Buldain who were hired roughly at the same time at the beginning of this decade, after WWI and the demand for Spanish that seemed to follow it. Two relevant characteristics could have been that of Spanish being their native tongue and their academic and life experience with a Spanish-speaking culture. Sendón was originally from Spain and Buldain had been a preacher both in Mexico as well as at a Mexican church in San Antonio. Without considering this emphasis on native tongue and culture, it could seem confusing that Garnett, holding a B.A. and an M.A., was not hired, while Sendón was hired without even having completed his B.A. Sendón was not even a Spanish major. However, President Brooks still sought him out and hired him. With this type of experience as a native as an apparent criteria, Garnett and Montgomery’s applications or resumès proved insufficient.

The Spanish Faculty at Baylor

Sendón had left Spain at a young age at his mother’s request because of persecution for their Protestant faith (not Catholic). However, he did not migrate to the United States but moved in with an uncle in Aguascalientes, Mexico, where he finished high school. He had earned a scholarship to study in Mexico City but this opportunity was lost due to the Mexican Revolution breaking out during this time (The revolution lasted from 1910-1920). He completed a seminary degree in Monterey, Mexico before moving to the U.S. He was studying chemistry in the University of Arizona when President Brooks heard about him through a missionary, and invited him to finish his studies at Baylor while teaching at the same time. He began as a student and teaching at Baylor in 1919, completed his degree in 1920, (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón), and then accepted a full-time position as Spanish professor the same year (Sendón, February 18, 1920).

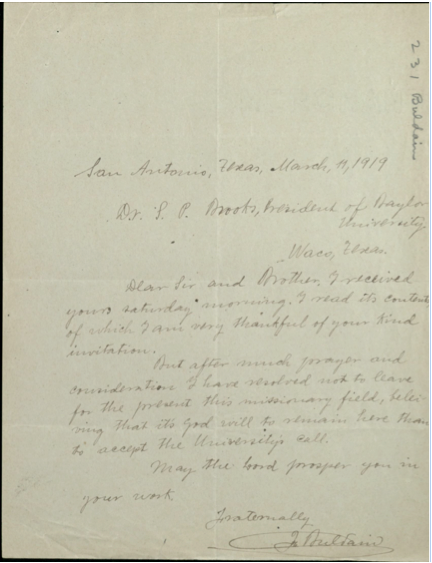

Buldain was a pastor at a Mexican church in San Antonio when President Brooks contacted him in 1919. Buldain’s resume reveals extensive preaching and engagements in different regions of Spain, Mexico, and Chile (Brooks, S.P., Buldain to Brooks, 1919). In correspondence with President Brooks, Buldain actually turns down the offer initially, stating he had “resolved not to leave for the present this missionary field, believing that it’s God’s will to remain here than to accept the University’s call” (Brooks, S.P., Buldain to Brooks, March 11, 1919). However, a letter dated three days later suggests a change of heart, as President Brooks rejoices that Buldain is “to be with us next year” (Brooks, S.P., Brooks to Buldain, March 14, 1919). Unexpected connections further abound: Sendón and Buldain actually knew each other already; upon arrival, Sendón was “surprised to find Mr. Felix Buldain, head of the department, whom I had in known in Aguascalientes, Mexico” (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón, p.7).

Sparkman began teaching at Baylor in 1913 after teaching at a public high school and Howard Payne University. He also worked in Cuba for a year in 1921, as several letters between him and President Brooks show (Brooks, S.P., Brooks to Sparkman, February 4, 1921; Brooks S.P., Brooks to Sparkman, February 23, 1921), and taught German at Baylor as well prior to this decade.

These faculty members, Sendón, Buldain, and Sparkman, remained Spanish faculty at Baylor for several decades and displayed these characteristics involving very high participation in the Spanish culture and language. This intentionality that President Brooks seems to employ in selecting the faculty of the Spanish department indirectly affected curriculum, as these professors worked to develop the department and expand the curriculum as explained in the following section.

Spanish Department: Process of Development

The beginning of this decade saw the arrival of valuable new faculty. This new faculty now faced the challenges of leading a small and developing department – one facing certain scrutiny, in particular from the declining but still strong classical languages. Sendón explains in an interview in 1971 of the presence of a certain attitude toward modern languages at times, especially during the debate about the Latin requirement and the importance of Latin.

But in those days, that is, there was an attitude among many people. They thought the languages should be relegated to second place in the curriculum. That was our first big fight in Baylor University. (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón, p.25)

Sendón also explains the need for reorganizing the curriculum at the beginning of the decade since previously it had been modeled after a Spanish literary manual. “It was an impossible program to follow, because we didn’t have the books, we didn’t have the materials, and we didn’t have the courses outlined” (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón, p.8).

The professors were sometimes asked to teach other things not related to Spanish. Sometimes this fell within their job description without much complication, such as Sendón teaching chemistry lab in the summers (due to his B.A. in Chemistry). The regularity of this is unknown, however. Brooks does inform Sendón in a letter to be ready to fill an additional position at any point in the summer if low demand for Spanish in the summer occurs. Sparkman did teach German for a time as well, and there is also record of him turning down a petition for teaching French to an Army camp in 1918. Though this correspondence did not initially involve President Brooks, Sparkman sent him the correspondence with his answer, stating “I am here at the expense of the university and am obligated to the university…” (Brooks, S. P., Sparkman to Brooks, July 5, 1918).

Sendón’s comment regarding having to change the curriculum sheds light on the lack of books for the use of the Spanish Department. Sendón contributed books and materials to the department and Baylor in a unique way—through his master’s degree. Sendón suggests his could be considered the “first self-taught master’s degree in Baylor University” (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón, p.11); he organized the materials for his courses, supervised by Sparkman and Buldain, wrote his own lectures, and added books to the library. Correspondence between President Brooks and Buldain in 1929 stating Brooks’ decision to purchase 61 volumes of “Nosotros” (probably a collection of Spanish books), serves as evidence of further expansion of Spanish curriculum toward the end of the decade. (Brooks, S.P., Brooks to Buldain, October 14, 1929).

Additional Spanish Programs

In addition to these curricular changes, the emergence of the Spanish club at the end of WWI, followed by the formation of Spanish labs in 1924 by Sendón, added a social and extracurricular dimension to the study of Spanish at Baylor. According to Sendón, while the Spanish Club emerged directly as a result of student demand (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón, p.15) he was the mastermind behind the Spanish lab. The labs served a similar purpose to that of the club but was a more controlled setting which allowed for beginner participation, which the Spanish club did not provide for as well (Baylor Lariat, Oct. 6, 1924, pp.1, 3). These labs often involved the acting out of “real-life” scenarios such as the barber scene (Baylor Lariat, Feb. 5, 1925) and business-like scene described in the Lariat (Baylor Lariat, Jan. 29, 1925).

Trips abroad as the one to Mexico City led by Miss Long, a faculty member at Baylor, were also a part of the Spanish program at Baylor. Miss Long had been a missionary in Mexico for eight years, once again stressing President Brooks’ preference for faculty with immersion experience. Though it is unclear how long she taught at Baylor, she did lead such trips as the one to Mexico City in 1922 described by former Spanish student Blonda Woodard, in an interview in 1976. The students on the trip describe Miss Long as competent and appreciated for her experience.

What makes this trip particularly remarkable is that it was only two years after the end of the Mexican Revolution, which makes it a fairly progressive ordeal. In her interview, Woodard even describes a situation in which a friend and her ended up separating from the group and taking a different train back to Mexico City, which was stopped and boarded by “some horsemen in caballero costume,” whom she thought might kidnap them (Owens, 1976, Interview of Blonda Alexa Weatherby Woodard, pp. 13,14). Compared to how study abroad is approached today, especially in regards to location and safety measures, this trip described by Woodard would seem risky to the Baylor (or American) student and staff member.

Additional endeavors to the learning of Spanish such as the Spanish labs and trips abroad enhanced the curriculum and stress the effort made by the faculty to further the Spanish department at Baylor. These programs were successful due to the increased interest in learning Spanish among Baylor students.

Conclusion

Baylor has proven to be a progressive school in its approach toward the education of modern languages. While President Brooks attempted to keep the prominence of the classical languages for as long as possible, Baylor was also the first university in Texas to teach Spanish (Walker, 1971, Interview of Andrés Sendón, p. 29). This new Spanish curriculum that developed in the decade of 1920 to 1930 contributed greatly to the success and growth of the Spanish department. Through course changes and additions, new faculty, and immersion trips abroad, it was able to keep up with the increasing societal demands for Spanish education. In subsequent decades , Spanish students and faculty at Baylor have profited from these endeavors, as Spanish continues to be studied today and boasts one of the largest departments at Baylor.

References

Baylor University. (1910). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor University. (1915-16). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor University. (1920). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor University.

Baylor Univeristy. (1930). Baylor University Bulletin. Waco, TX: Baylor Univeristy.

Brooks, Samuel Palmer. (1919 March 6). [Letter to Buldain, Felix M.]. Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C81, Folder #345). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Brooks, Samuel Palmer. (1919 March 14). [Letter to Buldain, Felix M.]. Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C81, Folder #345). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Brownlee, Milton M. (1924 October 6). Sendón starts new method of teaching Spanish department. The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/7664/rec1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Buldain, Felix M. (1919 March 11). [Letter to S.P. Brooks]. Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C78, Folder #306). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Brooks, S.P. (1929 October 14). [Letter to Buldain, Felix M.] Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C81, Folder #345). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Buldain, Felix M. (1919 March 6). [Resume of Buldain, Felix M.]. Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C81 Folder #345). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Downer, J.W. (1918 August 1). Status quo of latin. The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/5147/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Garnett, O.S. (1919 March 25). [Letter to S.P. Brooks]. Palmer Samuel Brooks Papers (Box #2C78, Folder #306). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Interview of Andrés Sendón by Thomas F. Walker. Baylor University Project for Oral History, 1971. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/buioh/id/2733/rec/8. Baylor University Institute for Oral History, Waco, TX.

Interview of Blonda Alexa Weatherby Woodard by Estelle Owens. Texas Baptist Oral History Consortium, 1976. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/buioh/id/2054/rec/18. Baylor University Institute for Oral History, Waco, TX.

Meyer, Ben. (1929 January 29). “Business taught in Spanish laboratory.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/7305/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Meyer, Ben. (1925 February 5). “Spanish Laboratory Scene of Barbering.” The Baylor Lariat. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/7609/rec/1. The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Montgomery, C.M. (1919 November 13). [Letter to S.P. Brooks]. Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C78, Folder #309). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Sendón, Andrés. (1920 February 18). [Letter to S.P. Brooks]. Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C78 Folder #311). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Sparkman, E.H. (1918 June 27). [Letter to S.P. Brooks]. Samuel Palmer Brooks Papers (Box #2C78, Folder #305). The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX.

Sparkman, Ellis Hugh. [vertical file, 1878-1952]. (Texas BU Subject Files). Texas Collection Vertical Files, Baylor University, Waco, TX.