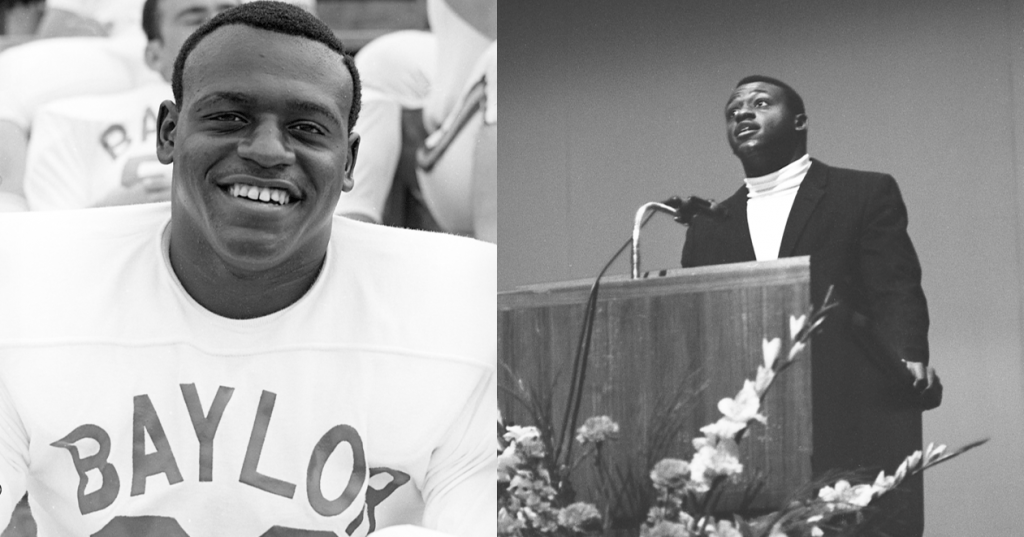

In September 1966 John Westbrook took a handoff, darted for nine yards, and became the first Black athlete to play football for Baylor and the Southwest Conference. His pathbreaking significance has been written about at several places over the years, including a feature story at the Baylor Athletics website. But there is another part of Westbrook’s story that has not been as well documented: his role as a pioneer in sports ministry.

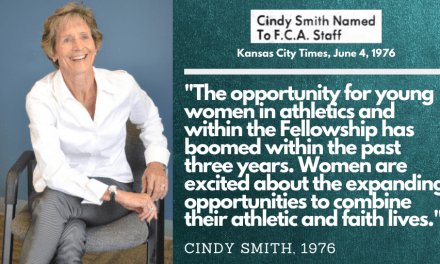

John Westbrook in his elements: football and public speaking. Photos from 1966. Courtesy of The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

In 1969, soon after graduating from Baylor, Westbrook became the first Black staff member hired by the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Before Westbrook, some African Americans had been involved in sports ministry. They spoke at evangelistic rallies, attended retreats, and wrote devotionals, among other tasks. But Westbrook was the first African American to have full-time employment in a major sports ministry organization. Although his time at FCA did not last long—he moved on to work in athletic administration and then as a pastor before passing away at age thirty-six in 1983—his presence deserves to be remembered.

But what, exactly, should we remember?

Besides Westbrook’s importance as a racial pioneer, I think there are three things in particular that we can learn from looking at Westbrook’s time in sports ministry.

- The complicated racial legacy of sports ministry organizations

In the United States today there are numerous sports ministry organizations filling all sorts of niches. But there are three main organizations that have the widest cultural reach and influence: the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, Athletes in Action, and Pro Athletes Outreach. All three are racially diverse, but have their origins in predominantly white institutions and constituencies. So how did they respond when the civil rights movement was gaining steam? Did they view racial diversity as a moral imperative back then?

Of the “Big Three,” only the FCA was in existence at the height of the civil rights movement (AIA and PAO were founded in the late 1960s and early 1970s). So it is through the FCA that we can best get a sense of the record of sports ministry organizations when it comes to civil rights.

On the one hand, the FCA was racially integrated from its origins in 1954. Even as it expanded in the segregated South during the 1950s and 1960s, it insisted on integration within its organization. To list one example: FCA leaders refused to hold a summer camp in the South until they had assurances that it would not be segregated.

The FCA also publicized stories of interracial cooperation. They portrayed sports as a way to accomplish gradual change, with Black and white athletes providing a model for the rest of society to follow.

On the other hand, the FCA never spoke out publicly in favor of civil rights legislation. Instead of seeing racial segregation as a moral blot on society that demanded immediate legislative attention, it preferred to offer up sports as an orderly way to bring about gradual change. Bill Bradley, a leading white spokesperson for the FCA in the 1960s, claimed that he left the FCA in the late 1960s because he was shocked to find that so many members of the organization opposed or indifferent to civil rights legislation.

When John Westbrook was hired by the FCA in 1969, this was the cultural context he was entering. He was joining an organization with a long history of racial inclusion, but with a tendency to center white perspectives and experiences. He was, as Jackie Robinson put it in his 1972 autobiography, a “black man in a white world.”

It is good for all Christians involved in sports ministry to wrestle with this history. As we look to the past we’ll find some things to be proud of, and other areas where we can learn and grow from sin, mistakes, and ignorance.

- The burden of the Black athlete

This point follows from the first. To look at Westbrook’s experience is to get a better sense of the unfair burden placed on Black athletes, coaches, and sports ministers as they entered into predominantly white spaces.

For Westbrook, we can see this most clearly from his time at Baylor. While Westbrook had many good things to say about his experience—he praised John Bridgers, his football coach, as a “wonderful man,” and stated that “there was no openly hostile racial difficulty”—he still felt like an outsider.

“I was on a team but it was like being in a room filled with people and not having anyone to talk to,” he said in a 1968 interview before his senior season. That loneliness took a mental toll on Westbrook. “Even with my faith I contemplated suicide several times,” he said.

In 1970 while he was on staff with FCA, Westbrook wrote in more detail about his struggles at Baylor. The title of his article? “I Was The Man Nobody Saw.”

If you ask white students who were at Baylor during Westbrook’s time, many of them would say they DID see Westbrook. I’ve spoken with a few of them and read their remembrances online. They describe Westbrook as friendly, kind, and good-natured.

How could Westbrook feel like he was not seen?

“Too many people didn’t look at me as John Westbrook,” he wrote. “They didn’t ask my aims in life or what I thought. When they looked at me, all they saw was black—and their thinking ended right there.”

Westbrook also felt the weight of an entire system of sports segregation placed on his shoulders. “I was always aware of who I was, and had to put up my front,” he recalled. “I felt like I was the guy that could take all the crap and I had to be the one to keep my head cool and that kind of thing, for the sake of somebody else coming along later.”

That was the burden Westbrook had to carry.

While we praise Westbrook for his courage as a pioneer, we should also lament the struggles that he faced. It was a burden he never should have had to bear. And while there is no doubt that progress has been made when it comes to racial demographics and opportunities in college sports and sports ministry, there is still work to do. One way to honor Westbrook’s legacy might be to consider the extent to which our spaces and institutions today continue to place greater burdens on Black athletes, coaches, and sports ministers.

- The value of honesty

The third and final thing we can learn from Westbrook follows from the first two: the importance of honesty.

Consider the two articles mentioned above: the 1968 interview and the 1970 essay. In recent years we have praised athletes for openly discussing mental health, portraying it as a brave new development. Westbrook was doing it fifty years ago!

For Westbrook, this openness was quite literally a matter of life and death. By his senior year, he decided he could no longer keep his feelings bottled up, pretending like everything was ok. He had to open up about his struggles—not just to the Black confidants who had always been there for him, but to white people in the Waco community as well.

When he was asked to do an interview for the Baylor Religious Hour about his experience at Baylor, he didn’t sugarcoat it.

“I told the truth as I saw it—of my loneliness, of the sin of stereotyping a man, either way,” he wrote in his 1970 essay.

Westbrook’s honesty did not bring about a miraculous change. It did not solve the problem of racism. But it did give him some breathing room. And it allowed people around him to get a better sense of who he really was and the depth of the struggles that he faced.

In sports ministry today, Westbrook’s honesty is a good practice to follow. Whatever the issue, Christian leaders in sports should work to provide spaces where honesty can flourish. They should confront difficult issues head on, instead of pretending like all is well.

If those in sports ministry can do these things—if they can practice and pursue honesty while working to learn about the racial dynamics of their organization’s past and present—they can honor the legacy of John Westbrook.