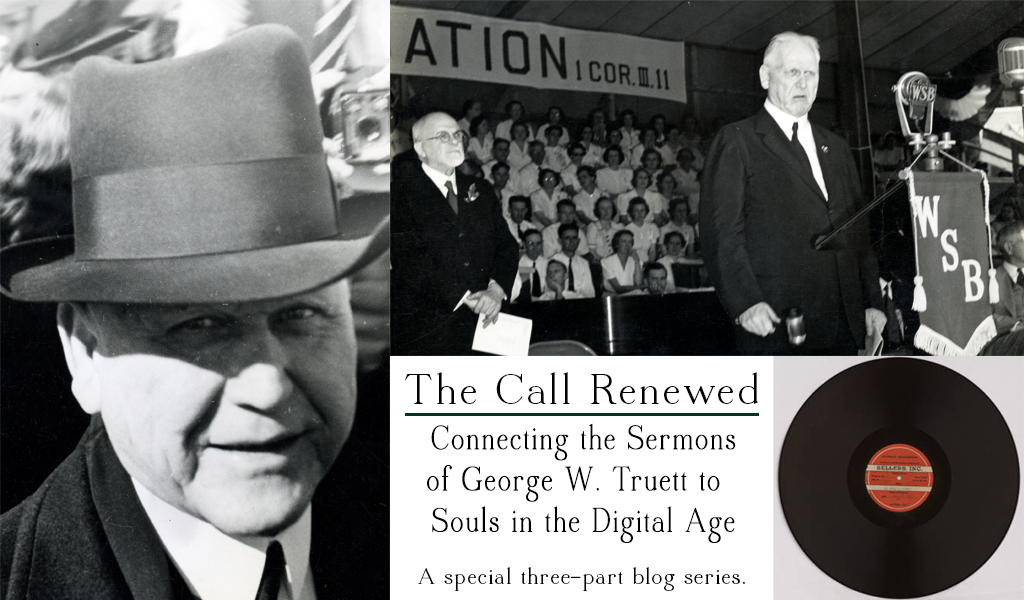

This is the second installment in a special three-part blog series on the project to digitize and present online the final sermons of George W. Truett (1867-1944), noted pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas and namesake of Baylor University’s George W. Truett Theological Seminary. Read the previous installment here.

The human voice is a powerful medium, surpassing the printed word in its ability to bestir, to convince, to cajole and – in the case of a pastor’s words to his congregation – to save. In a preliterate society the power of speech was the sole means of conveying an idea, rousing a people or sending along the latest gossip. And even after humans gained the skills to write down our thoughts via print and share them with others who spoke the same language, we find ourselves captivated, spellbound by someone with an ability to spin ideas from spoken syllables, to offer hope by the combination of his mind, his tongue and his vocal chords.

Perhaps that’s why there is such power in the recorded sermons of George W. Truett. It’s true that you can get the gist of his message by reading a transcript, either from our digital collection or in one of the many publications that cited his words. But nothing can replace the impact, the instinctive reaction that comes with listening to them, as clear as the day they were recorded over 70 years ago. Truett’s voice may occasionally waver, his cadence and phraseology may sound distinctly Southern and turn-of-the-19th-century, but when he infuses even a simple phrase or concept with the force of his well-honed speaking voice, it assumes an authority that can only come from a speaker who is supremely confident in what he has to say.

Building a Successful Sermon

Now that we’ve loaded approximately one-third of the sermons in the G.W. Truett Sermons Collection, a pattern has begun to emerge in the items I’ve encountered to date. While the content of each sermon is unique – covering everything from the Lord’s Prayer to Old Testament prophets and the application of contemporary world events with those experienced by the ancient Hebrews – the pattern of Truett’s delivery follows a noticeable pattern.

- Opening/Announcement

- Scripture reading

- Main point one

- Side point

- Anecdote

- Main point two

- Anecdote

- Main point three

- Altar call

- Dismissal/Hymn sing-out (occasionally)

It is tempting to label this approach as formulaic, but one must recall that Truett had been preaching for the better part of four decades by the time of these sermons’ delivery in 1941, so to a certain extent they must have come almost by second nature. In fact, while googling a number of passages delivered by Truett in this sermons, I came across several nearly word-for-word matches cited in books published in the early twentieth century. Why? Because they contained transcripts of sermons Truett had delivered as far back as 1917, the content of which was delivered almost verbatim in the 1940s. That makes his 1941 versions seem more like fond reminiscences of a life spent delivering God’s Word and less like rote repetition of a memorized formula.

Recurring Themes, Surprising Candor

In today’s megachurch society, with its emphasis on the “gospel of prosperity” and the myriad interpretations of what it means to be a Christian, listening to G.W. Truett’s firebrand Baptist delivery can be an eye-opening experience. He makes no bones about the foundation for his entire ministry:

Let me begin my message today by saying, quite personally, that for 40-odd years it has been my sacred privilege to preach from this pulpit. And through all these long years, I have had one theme, and that theme has been Christ. No other theme in all the world would challenge the attendance and the attention of men and women and young people for long, long years, except this theme: Christ. [1]

His major recurring theme, regardless the superficial theme of a particular sermon, is always the importance and urgency of bringing souls to Christ. Truett’s preaching carries a sense of impending doom for the unsaved, as one would expect from a favorite uncle or trusted neighbor who has your best interests at heart but has been unable to win you to his cause just yet. It is easy to see a major force behind his constant urging: the ongoing war in Europe, which would come to be called World War II and into which Truett would watch his country plunge in early December, 1941.

As our contemporary culture has moved further and further into a “you believe what you believe, I’ll believe what I believe and we’ll both be equally right” mindset, Truett’s candor regarding the way to salvation can strike modern listeners as shockingly exclusionary, even cliquish.

Salvation is not by a church, no matter what church. Greatly important as is the church as an institution, salvation is not by a church. All the churches in Christendom put together could not, in a million years, give the new birth to some soul wrong with God. Salvation is not by a church, nor by an ordinance, nor by a so-called sacrament, nor by some ritual – however imposing and impressive it may be – nor by some ceremony, nor by a creed, nor by a confession. Salvation, spiritual salvation for humanity, is by a person, and that person is Christ. Mark how he calls to us: “No man cometh unto the Father but by Me. I am the way, the truth and the life; I am the door. By me, if any man enter in, he shall be saved. He that climbeth some of the way is a thief and a robber.” [2]

Chances are you have heard the last half of this appeal (“I am the way, the truth and the life …”) but it is Truett’s dismissal of any other supposed road to salvation that may be hard for contemporary Christians to swallow.

The language Truett uses to describe life in the early 1940s may also surprise first-time users of the sermons. Americans today are hyper-aware of the words they use to describe people, concepts and events. For someone who has been raised to speak as neutrally and with as little opportunity to offend as possible, it may come as a shock to hear Dr. Truett refer to a boy with physical handicaps as “crippled.” Likewise, hearing him refer to someone as “dumb” or non-Christians as “heathens” may make contemporary listeners uncomfortable.

As with all of the materials in our collections, we urge our users to place these materials in their proper historical context. Truett was a man born just two years after the end of the American Civil War, educated and raised during the “Gilded Age” and matured during the rapid societal changes of the early 1900s. His language reflects his roots, his upbringing and his culture in the same way that today’s Americans are molded by the complex milieu of our societal surroundings. Users should be mindful that Truett’s language and style of delivery – including charming ways of pronouncing words like “parliament” (“pah-lee-ahh-ment”) and “Joshua” (“jaw-shoo-way”) – are reflective of the time and place when they were delivered.

Other notable features of Truett’s style include a fondness for alliteration, as evidenced in this passage from his sermon of June 22, 1941:

And what wonders can be done, sometimes with just one sentence. Many a life has been checked, challenged, changed by one sentence. You may have spoken it – you probably have.

Also making an appearance in this sentence is another of Truett’s rhetorical devices, namely, the use of three descriptors or examples to drive home a point. Truett seems to value the well-established efficacy of the concept of the “magic in threes” principle. Human brains are wired to respond more positively and effectively to a series of things that is odd in number, and three seems to be the most effective of all. An example of this, from the same sermon:

Here’s a talent we can use day or night, anywhere in the world we go, at any time: the talent of prayer. [3]

***

This is just a cursory look at the style and substance of Truett’s sermons, of course, and we welcome your in-depth examinations, comments and cross-postings as you get deeper into the collection. If you find a favorite passage or an insight you think is too good not to share, we’d love to see your tweets, Facebook posts or blog links. Send us a message at digitalcollectionsinfo@baylor.edu or like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/baylordigitalcollections to continue the conversation!

Works Cited

[1] From the sermon “Philip at Samaria.” Delivered March 16, 1941. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/ref/collection/fa-gwt/id/199

[2] From the sermon “What Think Ye of God?” Delivered April 8, 1941.

http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/ref/collection/fa-gwt/id/221

[3] From the sermon “The Gifts of God.” Delivered June 22, 1941.

http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/ref/collection/fa-gwt/id/289