My column this week looks at the artistic movement called “Realism” and the challenge of showing life as it really was.

Every time I teach the second half of the U.S. history survey course, the first artists I talk about in the Gilded Age are the ones grouped together under the classification of the “realists.” These were painters like Thomas Eakins, who sought to dispense with romanticism and idealization of life and to show things how they really were.

Eakins was born in Philadelphia in 1844 and lived most of his life there. In 1875, he painted one of his most famous pictures, “The Gross Clinic,” depicting a group of medical students operating on a patient under the guidance of a professor. The gritty portrayal of what surgery looked like and details like the blood on the professor’s hand and the grimacing woman near the table caused something of a controversy.

Fourteen years later, Eakins painted a similar scene titled “The Agnew Clinic,” and while it’s just as unflinching as the earlier work, one can clearly see how far medical science had progressed in the intervening years.

The lights are brighter, the young medical students and professor are all in white lab coats now instead of everyday dark suits, and an anesthesiologist is tending to the patient. Also a female nurse is standing nearby obviously unmoved by the scene, in stark contrast to the woman overcome in the 1875 painting.

The point of works like these is that, in addition to Eakins’ obvious skill as an artist, he’s providing a good account of what medical science really looked like in these years.

Other painters came along in his wake and continued his style of realistically portraying city life (particularly an unorganized group called the “Ashcan School”), but in terms of accuracy they could no longer compete with a new way of visual storytelling that was quickly becoming a sensation: photography.

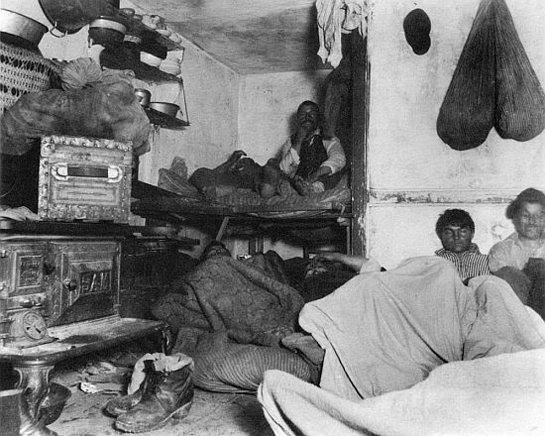

Jacob Riis was five years younger than Thomas Eakins and came to the U.S. from Denmark at age 21. For a while in the 1870s he was homeless in New York, sleeping in public parks and surviving on handouts. He finally found work as a reporter and then moved on to photography. Some of his photographs of the grim side of life in New York were so movingly graphic that they spurred cries for reform.

And so successful was photography at showing how things really looked — without the assumed influence of a painter’s skill with a brush — the assumption that paintings could portray reality all but disappeared.

A new exhibit opening this week at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, however, can remind us that we once depended on painting to show us reality.

“Eyewitness Views: Making History in Eighteenth Century Europe” is the only exhibit of its kind I’ve ever heard of. Most people will not know the artists included, but, honestly, great art isn’t the point. The curators explain that by focusing on historic events like pageants, ceremonies and even disasters “these paintings turn the viewer into an eyewitness on the scene, bringing the spectacle and drama of history to life.”

And they do. Of the ones I’ve looked at, perhaps the most striking is a 1765 canvas that depicts the ruins of a church in the city of Dresden that had been shelled by Prussian artillery during the Seven Years War. I’ve never seen anything like it, and it shows you a scene that, unless you know of this painting, can exist only in your imagination.

If you’re in Los Angeles between now and July 30, stop by the museum for a reminder that it was once painting that showed us what the world around us really looked like.