Fifty years ago this month, students in Baylor’s brand-new women’s residence hall — what is now known as North Russell — began classes for the fall 1962 semester. The three-story building had been conceived as a way to help relieve some of the overcrowding in Baylor campus housing being felt by the early 1960s.

When Baylor’s largest women’s residence hall, Collins Hall, opened its doors to 600 freshmen women in the fall of 1957, it had been the first time in 10 years that no women had been turned down for on-campus housing due to a lack of rooms. But the number of both men and women wanting to live on campus continued to grow, and within just four years Baylor was again busting at the seams.

At the time, Baylor’s six female residence halls had a capacity of 1,550 students, but prior to the fall 1961 semester a total of 1,850 women had applied for housing. The University did its best to cope with the shortages by putting three women in two-woman rooms in Allen and Memorial Halls, and by announcing in August 1961 that a change would be made to allow Baylor women to live off-campus in private housing, with parental approval. But it was obvious that these were only short-term measures, and since enrollment was expected to grow even more a long-term solution was needed.

When it came time to find land on which to build a new dormitory, Baylor was fortunate to be situated next to land that had been targeted for slum clearance through the federal Urban Renewal program in Waco. This land butted up to the northeast border of campus, roughly between between Baylor and the Brazos River, and also was located between the University and the land just to the west on which Interstate 35 would eventually be built.

On Dec. 6, 1961, the Baylor Board of Trustees authorized the letting of a contract for a new 90,000-square-foot women’s dormitory to be opened for 475 students at the beginning of the 1962-1963 academic year. Later that same day, the Urban Renewal Agency’s board gave its approval to a bid of $545,000 by the Baylor-Waco Foundation to purchase some of the cleared Urban Renewal land. The land would eventually be donated to Baylor, and part of it would be home to the new women’s residence hall.

On Dec. 6, 1961, the Baylor Board of Trustees authorized the letting of a contract for a new 90,000-square-foot women’s dormitory to be opened for 475 students at the beginning of the 1962-1963 academic year. Later that same day, the Urban Renewal Agency’s board gave its approval to a bid of $545,000 by the Baylor-Waco Foundation to purchase some of the cleared Urban Renewal land. The land would eventually be donated to Baylor, and part of it would be home to the new women’s residence hall.

The building would contain three wings and form a “U” shape, much like Baylor’s new Marrs McLean Science Building, which began construction around the same time. The original goal was to have two of the residence hall’s wings completed and in use by the start of classes on Sept. 5, 1962, with the third and final wing to be completed almost a month later on Oct. 1.

Construction began almost immediately and progressed rapidly — so rapidly that the building would be completed ahead of schedule, with all three wings open by the start of the fall 1962 academic year. By May 12, 1962, built-in furniture had been installed and the building was far enough along that female students were invited to attend an “open house,” which allowed them to take a peek inside a display room and get an idea of what to expect when the dorm opened in the fall.

Construction crews were rushing to get the building completed before move-in day. If you walk by the building today and look down at your feet, you can still see when the concrete sidewalks were laid — Aug. 22, 1962. The $1.5 million residence hall finally opened at the start of the fall 1962 semester as the new home for 475 women, 75 percent of those freshmen. The building didn’t have a truly permanent name when it opened. Everyone simply called it “New Hall.”

Construction crews were rushing to get the building completed before move-in day. If you walk by the building today and look down at your feet, you can still see when the concrete sidewalks were laid — Aug. 22, 1962. The $1.5 million residence hall finally opened at the start of the fall 1962 semester as the new home for 475 women, 75 percent of those freshmen. The building didn’t have a truly permanent name when it opened. Everyone simply called it “New Hall.”

An article in the Sept. 14, 1962, issue of the Baylor Lariat praised the ambience of the building. “Hallways are a light gray, which lend themselves to the coolness provided by air conditioning,” it said. “Restful and study-provoking colored walls of green, pink, beige and blue are a pleasing contrast to the natural-finished woodwork in each bedroom…Television lounges on each floor will serve doubly as clubrooms. Two spacious study rooms furnished with dark oak furniture are on each floor.”

An article in the Sept. 14, 1962, issue of the Baylor Lariat praised the ambience of the building. “Hallways are a light gray, which lend themselves to the coolness provided by air conditioning,” it said. “Restful and study-provoking colored walls of green, pink, beige and blue are a pleasing contrast to the natural-finished woodwork in each bedroom…Television lounges on each floor will serve doubly as clubrooms. Two spacious study rooms furnished with dark oak furniture are on each floor.”

Despite its rather bland name, New Hall was affected by some exciting social changes when it first opened. Assistant dean of women Viginia Crump announced that freshmen in New Hall and other female residence halls would have their curfew extended from 9 p.m. to 11 p.m., and could keep that later curfew as long as their grades didn’t drop. Also, since New Hall did not have its own women-only dining hall attached to it, Crump informed its female residents that they should dine across the street in the dining hall of Penland Hall, a men’s dorm. Officially mandated co-educational dining had not been standard practice at Baylor before that time.

As mentioned in a recent story in the Lariat, a large basement had been constructed under New Hall, mainly to be used as a bomb shelter in case of nuclear attack. The area was supposedly large enough to hold all the New Hall residents in the event of an emergency. When Lariat reporters toured the underground space in 2011, it still contained “a massive collection of U.S. government-issued cylinder bins” emblazoned with instructions on how to use the bins as either water storage units or commodes.

If things had gone as first envisioned, New Hall would not have been a women’s residence hall forever. Administrators originally planned to turn New Hall into a men’s dorm once a new women’s dorm was built somewhere near Allen Hall. But that new dorm never materialized, so New Hall has remained a home for Baylor women all its days.

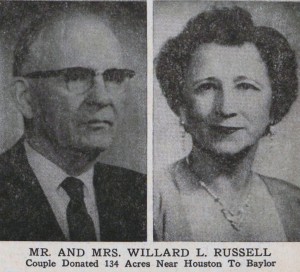

“New Hall” could not help becoming less and less new over the years, and on March 17, 1966, it finally lost its clunky original name. That day, Baylor trustees voted to change the name of New Hall to “Russell Hall,” in honor of Baylor graduates and benefactors Mr. and Mrs. Willard L. Russell. The Houston couple had recently donated 134 acres of land near Houston to Baylor, worth about $250,000 at the time.

“New Hall” could not help becoming less and less new over the years, and on March 17, 1966, it finally lost its clunky original name. That day, Baylor trustees voted to change the name of New Hall to “Russell Hall,” in honor of Baylor graduates and benefactors Mr. and Mrs. Willard L. Russell. The Houston couple had recently donated 134 acres of land near Houston to Baylor, worth about $250,000 at the time.

The familiar problem of too many Baylor women and not enough campus housing continued throughout the 1960s, and by the middle of the decade it was clear that Baylor needed an additional women’s residence hall. Instead of building a new facility near Allen Hall, as was originally planned, trustees decided to add on to Russell Hall. The dorm’s U-shape was transformed into a rectangle with the addition of a second U-shaped dorm that connected to the previous one. This new three-story facility — called South Russell Hall — was completed in 1967, and the original section of residence hall became known as North Russell.

South Russell would be the last campus housing facility that Baylor would build for almost four decades. In 2004, the University dedicated the North Village Residential Community, a beautiful coeducational complex that has sparked a new era in residential living at Baylor.

(Clippings from the Lariat courtesy of Baylor Libraries Digital Collections)