The legacy of Dr. William Hillis lives on in students who learn to love medical research

By Randy Fiedler

Longtime professor and administrator Dr. William Hillis is somewhat of a living legend at Baylor University. But if it were not for a few instances of divine intervention, this respected science educator might not have made it to the University where he has influenced multiple generations of healthcare professionals.

Longtime professor and administrator Dr. William Hillis is somewhat of a living legend at Baylor University. But if it were not for a few instances of divine intervention, this respected science educator might not have made it to the University where he has influenced multiple generations of healthcare professionals.

Hillis, Baylor’s Cornelia Marschall Smith Distinguished Professor of Biology, came to the University from Fort Worth. He graduated in 1953 with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry –– earning the Alpha Chi award for the highest senior grade point average in the process. After earning a medical degree from Johns Hopkins University, he spent the next 25 years as a scientific researcher, physician and medical school professor.

In 1964, during his time as a medical researcher in the U.S. Air Force, Hillis took his family with him to the newly independent African nation known as the Republic of Congo, which had thrown off Belgian colonial rule four years earlier. He went to the country to catch the wild chimpanzees he needed for his research on a vaccine for hepatitis.

It wasn’t until after he arrived in the Congo that Hillis discovered he’d come to a country in the middle of a growing revolution. He said he learned that native tribesmen, who blamed their former Belgian rulers for the difficulties the country was then facing, had sworn to kill any Europeans or other white people they came across.

Hillis first encountered these natives while driving back alone from the jungle. After being forced to stop at a crudely built roadblock, he was soon surrounded by tribesmen wearing headdresses.

Hillis first encountered these natives while driving back alone from the jungle. After being forced to stop at a crudely built roadblock, he was soon surrounded by tribesmen wearing headdresses.

“The American military advisory group had lent me an Army .45 pistol,” Hillis said. “I had it in the front seat with me, and so when (the rebels) started approaching me I just reached out the window and shot the gun up into the air. That scared them off –– they backed away, and I drove through the barrier.”

As the violence in the Congo escalated, Hillis’ wife and children were evacuated to the nearby country of Burundi while he stayed behind in Bukavu to provide medical care. Soon, he got word that the rebels were advancing on the city.

“I knew the rebels were sworn to kill all the white faces,” Hillis said. “I prayed if there were any way for the Lord to get me out of there safely, I’d forever be in his debt.”

“I knew the rebels were sworn to kill all the white faces,” Hillis said. “I prayed if there were any way for the Lord to get me out of there safely, I’d forever be in his debt.”

Just when it appeared that the rebels would arrive at any time, Hillis was interrupted during his prayer time by a fateful phone call from the American consul general.

“He said, ‘Dr. Hillis, I’m totally surprised by this, but a plane has landed here in Bukavu and it’s going back to Bujumbura [where your family is]…I took the liberty to make a reservation for you. It’s the last seat that was available,’” Hillis remembered the consul general telling him.

With takeoff only a few minutes away, Hillis hurried to board the plane and was soon reunited with his family. But after his arrival in Bujumbura, Burundi, he received shocking news from the American ambassador there.

“He said that one hour after my plane departed, the American ambassadorial staff in Bukaru and all the Europeans there were killed by the rebels. That night I remembered falling down on my knees and asking God why I had been spared out of all those people,” Hillis said. “I couldn’t understand anything at all about that until finally one day it occurred to me that I’d been saved for a purpose.”

One thing Hillis eventually realized was that God had given him a love for teaching and a desire to encourage students to pursue scientific research that could benefit mankind.

“So that’s when I came back to Baylor,” he said. He returned to the University in 1981, at the request of new president Herbert H. Reynolds, to chair Baylor’s biology department. Hillis later became Baylor’s executive vice president and then vice president of student life.

During his time at Baylor, Hillis also was instrumental in helping introduce the study of medical humanities and ethics on campus. Today he remains active by speaking to student medical associations, mentoring prehealth students with their research and teaching a freshman academic seminar. Helping students navigate their future as healthcare professionals remains one of Hillis’ passions.

“I feel like my role in medicine became to prepare doctors to go out and live meaningful lives,” he said. “I’ve tried to teach all of them that unto whom much has been given, much would be required.”

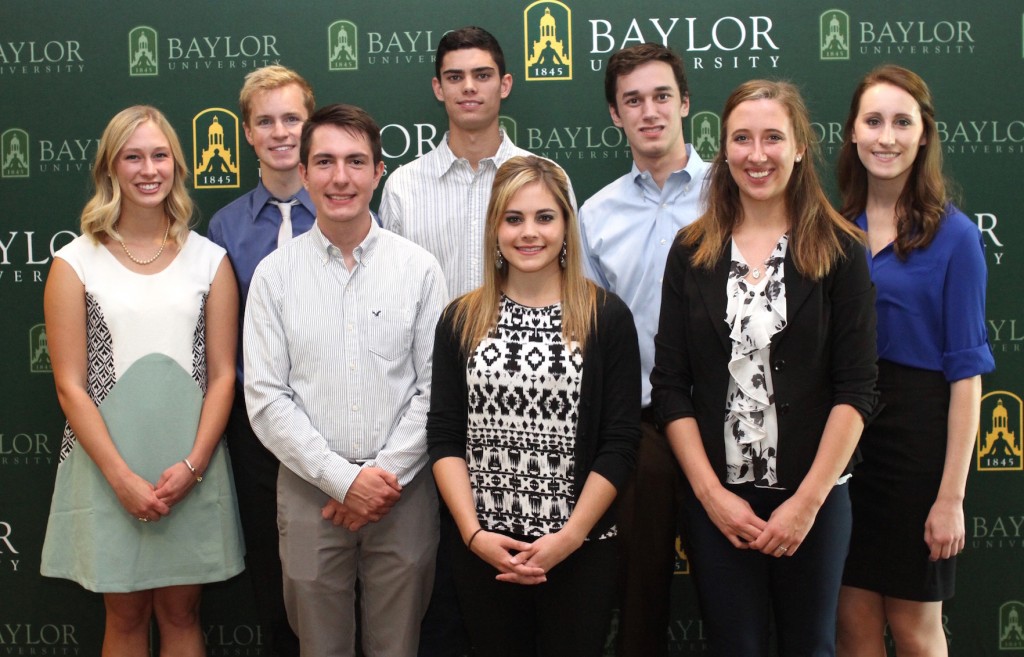

To honor Hillis’ dedication to helping students succeed, Baylor has created a new scholars program in his name. Funded by gifts from the Baylor family, the program provides prehealth students with needed financial assistance. The inaugural class of 12 students named as Hillis Scholars was presented in October 2015.

“I am extraordinarily humbled by this,” Hillis said. “I want very much for the Hillis Scholars Program to have success because I want our students to have the opportunity to do research while in school. They’ll know how to approach new problems in medicine, and how to solve those problems.”

For information on the The William and Argye Hillis Scholars in Biomedical Science Program, visit www.baylor.edu/hillis.

————————–

A version of this article first appeared in the Fall 2013 issue of Baylor Arts & Sciences magazine.

————————–

UPDATE: Dr. William Hillis passed away on April 26, 2018, at age 84. His wife, Argye, preceded him in death on April 29, 2017.

[…] military never even occurred to me,” Matthews remembers. “But the greatest mentor I ever had, Dr. Bill Hillis [BS ’53, the longtime Cornelia Marschall Smith Distinguished Professor of Biology], announced an […]