Elesha Coffman

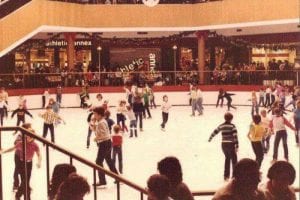

In a recent issue of the New York Times magazine, the “Letter of Recommendation” column touted “Dead Malls.” I was reminded of the malls I grew up with, in central Indiana in the 1980s. The best one was the Glenbrook Mall in Ft. Wayne, where my parents would do the Christmas shopping while my sister and I skated at the ice rink in the center:

(image from Pinterest; to my knowledge, I am not in the picture)

To think more about the history of shopping malls in the United States, I read Alexandra Lange’s article, “Malls and the future of American retail,” from Curbed. The article confirmed some details that I knew. Shopping malls largely date from the period after World War II, a time of increased consumer spending and suburbanization. Hundreds of malls were built in subsequent decades, but many of those are now closing or being dramatically repurposed, because people can buy things online instead and “hanging out at the mall” has lost much of the cachet it once (rather inexplicably) had. Large population shifts have also contributed to these trends. The postwar “white flight” from cities to suburbs has, in many places, reversed. The young, affluent (and still mostly white) Americans who are now gentrifying city centers do not want to drive all the way out to the suburbs, walk through an enormous parking lot, and shop in bland department stores with bad lighting. They want bold architecture, local flavor, landscaping, and spa services, and they want it all to be accessible via public transit.

The most obvious of the “Big Ideas” for this course that arises in the Lange article is unacknowledged assumptions. Shopping mall builders assumed that people would always do most of their shopping in person, back when nobody could imagine the Internet. Mall builders also assumed that suburban sprawl would just keep going and going, so a shopping center on an affordable, somewhat isolated lot would one day be surrounded by customers. This assumption about suburban sprawl was not entirely wrong, as many metro areas are still expanding in all directions, but the perception of urban centers as stylish and exciting, rather than decaying and dangerous, caught many planners by surprise.

The Lange article also highlights the interplay among business, state, and society. Malls might seem to be purely commercial spaces, but several public entities or concepts crop up in the article: the Department of Motor Vehicles (many DMV offices are located in malls), transit hubs, the Staten Island Ferry, state subsidies. Malls were always, in a sense, collaborative efforts of businesses and the state, because suburbanization would not have been possible without the G.I. Bill, which funded housing for WWII veterans, and the Eisenhower Highway System. Zoning policies, approaches to crime and education, “War on Poverty” programs, and other government interventions shaped cities and suburbs, too, as described in this paper from an undergraduate research journal at the University of Florida.

More significantly, the article speaks to Philip B. Scranton’s claim that “[i]nside a business there’s a minisociety” (MP, 9). A mall really is a minisociety, complete with food, employment, commerce, parks, social services, “mall cops,” etc. Lange argues, though, that it is a society with severe limitations:

However you remix the words “city” and “center”, however many public functions you invite in, however your sustainable landscape encourages walking (or hides the parking), it still isn’t the city. It’s a version of the city edited for the audience the owner and retailers want to attract.

All the mockery of the idea of Apple Stores as “town squares” multiplies tenfold—though malls, at least, must incorporate public bathrooms. No loitering policies, parental escort policies, and curfews explicitly exclude homeless people and teenagers from the mall. The economic mix of stores and the food options presents an implicit form of exclusion, as does the presence or absence of seating. The new urban malls must be responsible about the semi-public part of the equation.

A mall is perhaps the ideal place to examine questions of business and the meaning of society, all while sipping boba tea or looking for a good deal on shoes. Good luck finding a place to sit.