Preston Taylor

In an episode of the popular podcast “Planet Money,” Kenny Malone and Karen Duffin investigate the effects of Jimmy Carter’s plan for the government to buy dairy products during his presidential term. Entitled “Big Government Cheese,” this explains the downside of a specific government subsidy and the impacts it may have down the road.

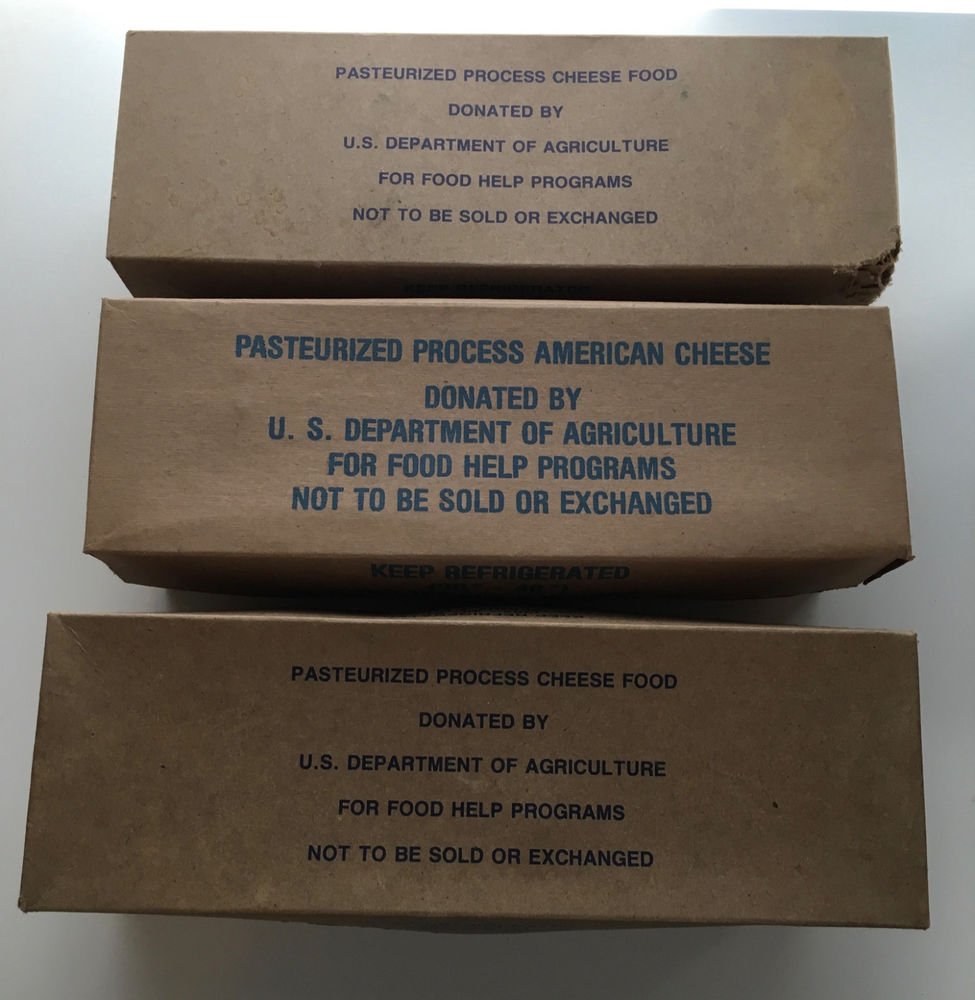

(Image from Twitter)

I was interested in this particular podcast because I love observing the impact when government interferes in the economy. It seems to me that often enough, the end result is worse off than before the original meddling. With this in mind, this topic immediately seems to follow the business, state, and society Big Idea that we have been focusing on. According to the podcast, this whole idea started as a far-fetched campaign promise to increase income for dairy farmers. In truth this is a fairly common occurrence as government subsidies are given to those who grow corn and many other agricultural products to increase production of certain goods. The problem with this particular subsidy is milk products cannot easily be stored in a silo for long periods of time as corn can. The solution was to turn it into cheese, which can be kept for a longer time than regular milk. So the government began buying large quantities of cheese which they stored in underground caves that served as natural refrigerators. They then processed the cheese into two and five pound blocks, wrapped in simple brown paper, and redistributed them to schools, the military, and food banks at no cost to consumers.

DUFFIN: This is a basic supply-and-demand problem. The government was demanding an unnatural amount of milk and so farmers were supplying an unnatural amount of milk.

Any time you have a greater production of a good than the popular demand for that good, as occurs with government subsidies, there are multiple problems that arise. A surplus of cheese was created, essentially meaning that there was more cheese available than people were willing to buy. If the government attempted to sell the cheese to ordinary consumers the price would drop below profitable rates for the farmers who were supposed to benefit from the subsidy in the first place. Thus the government gave the cheese away to a consumer group that would not have the resources to buy cheese in the first place: the homeless and impoverished in many urban centers.

The government now needed to wean the production of dairy down back to its normal rate, so instead of simply purchasing cheese, they implemented a policy of direct subsidization where the government directly paid dairy farmers to NOT produce milk. They also created ad campaigns like the famous “Got Milk?” to try and increase consumer demand, and slowly return the supply and demand curve to its normal, equilibrium state.

This is just one example of government subsidies creating conflict in the free market. The creation of surpluses rarely ends in a societal benefit and this article about fossil fuels serves as another instance where government interference in business creates problems for the average consumer. When it comes to topics of business, state, and society, it is my opinion that the market works best when left to fluctuate according to its natural processes. And the idea of making cheese purchases to bolster the economy is as far fetched as it truly sounds.

Certainly, subsidies are unpopular in business and economic literature. (I just glanced through a bunch of it online.) But I wonder if part of the reason for this judgment is what gets labeled a “subsidy.” For example, cities and states often give tax breaks to businesses to lure them to relocate. These places get labeled “pro-business.” How is a tax break not a subsidy? The main difference seems to be that business and economic writers like one of these things and not the other. For example, over at the Mises Institute, an author insists, “Exemptions and loopholes do not forcibly redistribute wealth; taxes and subsidies do, thereby benefiting some producers at the expense of others.” I’d say that exemptions and loopholes absolutely benefit some producers at the expense of others, and the resulting hyperconcentration of wealth is not, on its face, less problematic than a redistribution would be. It becomes an argument about what constitutes justice and social good, which neither side is going to “win” decisively. My point is, you can only start to have that argument once you decide not to define subsidy as “stupid government meddling,” but see the relationship of business, state, and society as more complex and multifaceted than that. (The cheese thing, though, that really was stupid government meddling.) https://mises.org/library/no-tax-breaks-are-not-subsidies