Charlotte M. Yonge. Musings over the “Christian Year” and “Lyra Innocentium.” 2nd ed. Oxford: James Parker and Co, 1872 ABLibrary 19thCentury Collection PR4839.K15 Z9 1872

John Keble. The Christian Year: Thoughts in Verse for the Sundays and holydays throughout the Year. 2nd ed. Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter, for J. Parker and C. and J. Rivington, 1827 ABLibrary 19thCentury Collection PR4839.K15 C4 1827

Rare Item Analysis: The Bible Extension that Nobody Asked for, but (almost) Everyone Loved: John Keble’s The Christian Year and Reactions

By Ileyah Tovias

COVE timeline | COVE timeline entry | COVE map

My presentation involves two rare items: Charlotte M. Yonge’s Musings over the “Christian Year”and John Keble’s The Christian Year. The copy of The Christian Year that the Armstrong Browning Library possesses is a second edition. Both of these items are held in the 19thCentury Collection of the Armstrong Browning Library. I’d like to mention that both of my rare items are the same rare items used by Christopher Yang in a previous blog post titled “Private and Public Interpretations of John Keble’s The Christian Year.” Yang focuses on annotations made in the edition of The Christian Yearrelating to Keble’s poem titled Holy Innocents, as well as Yonge’s comments about the same poem.

I’d like to discuss Keble’s “Morning” meditation and his “Wednesday before Easter”and Yonge’s reactions towards them. I was interested in the possibility of other sects of Christianity using The Christian Year, and I found the circular ending and generally positive message of Wednesday before Easter fascinating. Regardless of an individual’s personal use of The Christian Year, what is most important is how admired Keble’s collection of poems was throughout its period of popularity before abruptly being out of use.

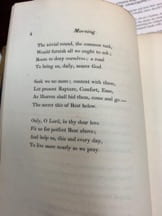

While John Keble composed a poem for every Sunday in the calendar year, he also included passagesrelated to Anglican ceremonies, such as Communion and Baptism. While the core of his content centers around Sundays, as well as the days leading up to a significant religious holiday such as Easter, Keble composed poems to accompany the morning and evening prayers assigned for every day of the year by the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, which The Christian Year was designed to accompany. In doing so, Keble encouraged readers to be active daily in the readings of The Christian Year, even if it was not Sunday. Each poem stemmed from verses in the Bible, many of which were assigned for prayers and services by the Book of Common Prayer, and Keble’s poem for ‘Morning’ prayer is inspired by a section from Lamentations, which is inscribed as follows: “His compassions fail not. They are new every morning.” Keble’s “Morning” can be interpreted as a joyful poem, reveling in the fact that we wake up to “New thoughts of God, new hopes of Heaven” (Keble 2). Keble is generous in the amount of details he writes about nature. This poem is primarily dealing with the marvels of nature and how it is all created from the hands of God. This is a commonly accepted belief among Christians, which helps to explain why other sects of Christianity than Keble’s own Church of England used The Christian Year.

Charlotte M. Yonge describes “Morning” as “a realization of how we may walk day by day in newness of life, and how the old becomes more and more dear for the new radiance continually shining on it” (Yonge 2). She does not have many negative reactions to this poem. Her main critique of “Morning”is that “the poem is perfect as a morning meditation, but is forced out of its use when sung like a hymn of praise” (2). It should be noted that Yonge was inspired by Keble and was a well-educated woman who was titled the “Novelist of the Oxford Movement,” a movement Keble himself was very involved with. Her works were well-received amongst others, so her “musings,” as she titles them, would not be seen as trivial in her time.

Keble uses a verse from Luke for “Wednesday before Easter:” “Saying, Father, if Thou be willing, remove this cup from Me: nevertheless not My will, but Thine, be done.” Historically, the Wednesday before Easter is also known as Spy Wednesday. This is the day Judas Iscariot plans to betray Jesus in exchange for a monetary reward. This is the turning point that ultimately leads to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. In some services, this day is seen as a day of darkness and sorrow. Keble’s poem does not symbolize that. Instead, he focuses on the Lord’s will and the obedience we must follow. In his opening lines, he seems to be speaking directly to God when writing,

O Lord my God, do Thou thy holy will –

I will lie still –

I will not stir, lest I forsake Thine arm,

And break the charm,

Which lulls me, clinging to my Father’s breast,

In perfect rest. (64)

Compare this to the poem’s closing lines:

“O Father! Not my will, but thine be done” –

So spake the Son.

Be this our charm, mellowing Earth’s ruder noise

Of griefs and joys;

That we may cling for ever to thy breast

In perfect rest! (66)

One immediately notices the circular ending, which I could not help but connect to the resurrection of Jesus. Even though Jesus was betrayed by Judas and eventually crucified, he rose again and is eternal.

Yonge seemed to think this as well. She believed “the point is not what kind of outward circumstances are ours, but whether we seek our own will, or bend to the will of God. In accepting that will, whether in grief or joy, is alone perfect rest! (113-14).

I found this interpretation of Spy Wednesday particularly interesting. Keble had the ability to construct the poem however he wanted to, and he chose to compose it in a positive light that was, at the very least, well-received by a colleague. In the time of The Christian Year’s popularity, it was printed hundreds of thousands of times; its impact was humongous. While John Keble initially wrote this for the Church of England, it was admired by other sects of Christianity. Although not part of Keble’s plan, this admiration from other Christians probably resulted in The Christian Year’s growing popularity. Keble was very influential with this piece and it was used alongside the Bible for decades, which is no easy feat. It would be interesting to consider the idea of reviving or adding to The Christian Year for current Catholic or Anglican churches to use. Even if it remained the same, it is unknown whether or not The Christian Year would be popular in churches today.