Robert Browning, Bells and Pomegranates (1841-46) pamphlet collection copy six in eight parts (ABLibrary Rare X 821.83 P1 M937b c.6)

Rare Item Analysis:

by Alexa Welch

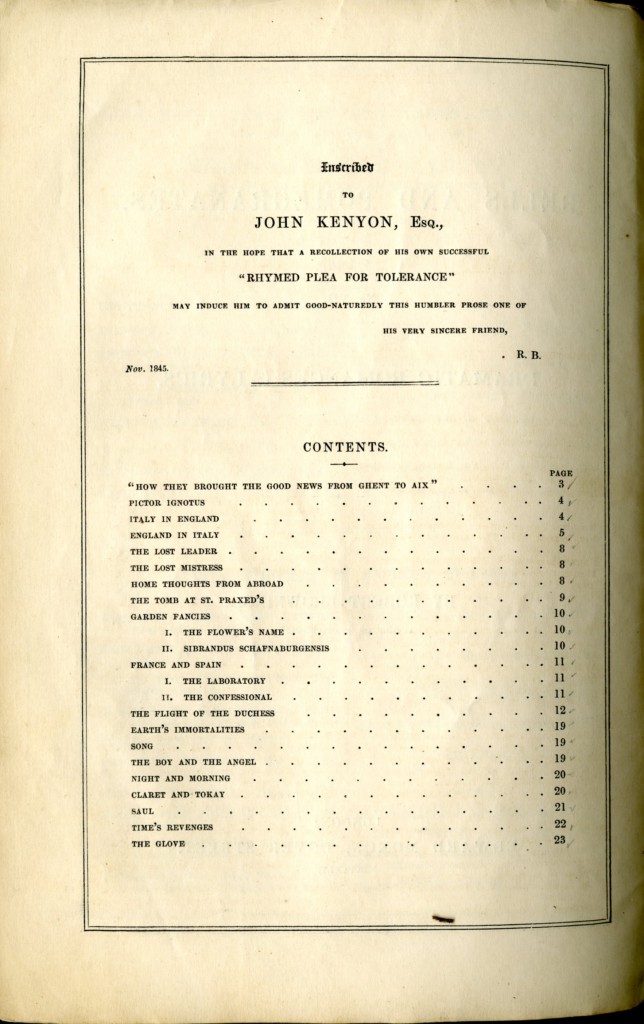

Robert Browning published his famous work, Bells and Pomegranates, in the form of eight separate pamphlets. The purpose of this collection was to get his works into the most hands possible by not having it bound as an expensive book. We are lucky enough to have nine copies here at the Armstrong-Browning Library. The sixth copy held in the Armstrong-Browning Library’s ABL Rare Books Collection has Robert Browning’s own inscription made out to an “F. Stone Esq.” An online copy of the first of the volumes can be located through BearCat at this link: http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112067508694;view=1up;seq=15 .

Browning’s construction of the Bells and Pomegranates breaks his poetry into groups, and frequently into paired poems. Some of the poems in this collection were previously published in the Monthly Repository, a British monthly magazine that was published in the early 19th century up until 1838. Perhaps the most famous works from Bells and Pomegranates are in the third volume: Dramatic Lyrics. In this volume you will find early versions poems such as “My Last Duchess” and “Porphyria’s Lover.” However, should you find yourself looking at the table of contents on this volume you will find neither of these poems listed. With this first edition we have the opportunity to see these works as originally conceived by Robert Browning.

“My Last Duchess” and “Porphyria’s Lover” are two separate instances of Browning having originally paired two poems with other works. “Italy” is the title that you will find “My Last Duchess” listed as, and it is next to a poem entitled “France.” Later renamed as “Count Gismond,” “France” is similar to the aforementioned poem in that it details the story of a woman who doesn’t reserve her attention for only her husband. The pairing of these two creates a parallel between the women and encourages the audience to see the stories and their similarities. Are the duchess and countess guilty of the same crimes against their powerful husbands? Ought we reconsider the ending of the duchess in light of Gismond’s fight for the countess? This pairing shows two powerful couples in two powerful countries and how similar their marital issues might be. Browning insists that the people of Europe were citizens of the same world and could find more similarity than might be expected of different nationalities.

The shocking story of “Porphyria’s Lover” —also contained in the third volume—is paired up with Browning’s “Johannes Agricola in Meditation” under the name “Madhouse Cells.” The two poems seem entirely different because of their subject matters: the contemplations of a religious man and the story of a man who kills the woman that he loves. However, this pairing forces the reader to see the similarity between the two. Neither narrator has a healthy understanding of his position in the world and what is right. The benefit of this pairing, and its title, forces the reader to see the madness in both men. Even if you aren’t entirely aware of the Catholic heresy in the meditations of Johannes Agricola, you might see the evil in the murder described in “Porphyria’s Lover.” One of the downsides of this pairing might be that it does not allow for the audience to agree with either of the poems subjects. The shocking twist in “Porphyria’s Lover” is hinted at with the title of the two works since it follows “Johannes Agricola in Meditation.” As a result, the audience is expecting something decidedly deranged to occur.

After the publication of Dramatic Lyrics, the four poems were all separated and given the titles that we know them by today: “My Last Duchess,” “The Count Gismond,” “Porphyria’s Lover,” and “Johannes Agricola in Meditation.” In the first volume of Bells and Pomegranates, we see another change in title. The poem we know as “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church” was first published as “The Tomb at St. Praxed’s.” This might seem insignificant, but the new title better establishes what happens in this poem: the bishop requests a specific design for the tomb that he will hold him. What the new title establishes is a question in the reader’s mind: why is the poem about the tomb he ordered and not called simply “The Bishop’s Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church”? The title change encourages the reader to question whether or not the Bishop’s requests are even followed. This minor title change to a poem that kept every line in the original gives us a small insight into how Browning wanted the reader to see his poems.

The beauty of a first edition is not to be limited to its monetary value. From the first edition we can see Browning’s early attempts to collect his poems and look at how they have changed. I would encourage you that even if you can’t read through the works, take the time to identify your favorite of his poems and see just how much they’ve changed since Browning first published them in his delightful Bells and Pomegranates.