By Benna Vaughan, Manuscripts and Special Collections Archivist

“We expect to speak with one voice on all matters affecting this hemisphere. Mr. Mann will be that voice.” Thomas Mann earned that vote of confidence from none other than Lyndon B. Johnson–by the early 1960s, Mann had twenty years of service in Latin American diplomatic relations and had earned the nickname, “Mr. Latin America.” The Thomas C. Mann papers at The Texas Collection provide a look at Latin America through the materials of a career foreign diplomat during the 1940s-1960s.

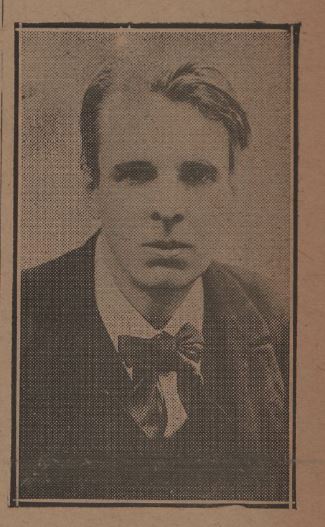

Thomas C. Mann was born in Laredo, Texas, on November 12, 1912, where he grew up bilingual due to the close proximity of his hometown to Mexico. Mann attended Baylor University from 1929-1934, earning a BA and then an LLB from Baylor Law School. He married Nancy Aynesworth, daughter of Dr. Kenneth H. Aynesworth (considered a founder of The Texas Collection), and spent 1934-1942 working at his father’s law firm in Laredo.

Mann began his foreign diplomatic career when he hired on with the State Department in 1942. Mann tried to enlist in WWII military service but was turned down because of his poor vision. Instead, he was asked to join the State Department, partially because of his bilingual abilities–he was a perfect fit for service in Latin America. He was Special Assistant to Montevideo, Uruguay in 1942-1943. From there, he became Assistant Chief in the Division of World Trade Intelligence (1944-1945), Assistant Chief in the Division of Economic Security Controls (1945-1946), Chief of the Division of River Plate Affairs (1946-1947), and then Second Secretary in Caracas, Venezuela (1947-1949). Mann was Deputy Assistant Secretary for Middle American Affairs from 1949-1953, during which time he worked closely with the new Eisenhower Administration on Latin America policy.

The only break in Latin American diplomatic service was in 1953-1954, when Mann became Counselor to Greece. But when President Jacobo Arbenz was overthrown in Guatemala in 1954, Mann was quickly brought back and assigned the office of Deputy Chief of Mission to that country, where he served one year. In 1955-1957, Mann was the Ambassador to El Salvador, and then in 1957 was appointed Assistant Secretary for Economic Affairs, a post he would hold until 1960. Mann would hold the office of US Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs twice, from 1960-1961 and then from 1964-1965. Between those years, from 1961-1963, he served as Ambassador to Mexico. Mann’s last diplomatic office was that of US Under-Secretary of State for Economic, Business, and Agricultural Affairs from 1965-1966. Mann retired from diplomatic service in 1966 and went to work for the Automobile Manufacturer’s Association from 1967-1971.

One of the most remarkable series in the papers is the Oral History series. Mann served under five U.S. presidents (Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson) and the oral history interviews Mann did for the Presidential Libraries of four of the presidents are very insightful. The oral history for the Kennedy Library is particularly interesting as it discusses a foiled assassination attempt on Kennedy when he was in Mexico in 1962. Mann also goes into some detail on his thoughts and understanding regarding the Bay of Pigs and events surrounding it, as well as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Each interview gives focus on a president, foreign policy and actions during that period (with the exception of the John Foster Dulles Oral History), and taken together, provide strong insights into the Latin American political landscape during those years.

Mann was also instrumental in helping to finalize the decades-old dispute between the US and Mexico regarding the boundary lines between the two countries, during his tenure as Ambassador to Mexico from 1961-1963. The boundary between the two was the Rio Grande, which had changed its course over the years, sometimes adding land to one country while taking it from another. Attempts at defining the boundary to the satisfaction of both countries had failed up until this time, and Mann played a large part in the discussions and negotiations which formally finalized the dispute, called the Chamizal Agreement, in January 1963. There are also two folders of recorded telephone conversations with LBJ in the collection that are very interesting to read and detail many conversations between the two from January 1964-June 1966.

Mann’s career is full of interesting events and situations, and his papers reflect that diversity. He was involved in the the Panama Canal Dispute and the Dominican Crisis in the early 1960s. He helped secure aid for fledgling governments in countries such as Bolivia, Brazil, and Chile. During his career, there was not much that went on in Latin America that Thomas Mann didn’t know about. His papers provide great insights into this long and interesting diplomatic career and also provide a wealth of research potential in the area of US-Latin American relations.

Gross, Leonard, “The Man Behind Our Latin American Actions,” Look, June 15, 1965

O’Leary, Jerry, Jr., “Portrait of a Diplomat: Mann Is a Forceful Loner,” Sunday Star, Washington, D.C., September 13, 1964

Meyer, Ben F., “Thomas Clifton Mann Receives Mexican Citation For Outstanding International Relations Achievement,” Baylor Report, May 1968