by Rachel DeShong, Special Event Coordinator and Map Curator

This blog post is the second in a series of three posts highlighting John Melish, a 19th century cartographer, and the impact his 1816 map, Map of the United States with the Contiguous British & Spanish Possessions, had on U.S. history.

Popular Graphic Arts, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-10486.

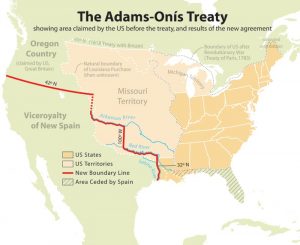

The Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 was the culmination of prolonged boundary disputes between Spain and the United States. Spain was attempting to retain their colonial empire in the Americas which was crumbling at the hands of revolutionaries. The United States, on the other hand, was rapidly expanding its borders but was highly concerned about the British presence in Florida. Although officially recognized as Spanish territory, Florida was heavily influenced by British mercantilism. During the War of 1812, British naval vessels used Florida as a launching point for attacks on New Orleans and other ports of the American South. Moreover, the United States had growing concerns regarding the number of runaway slaves and Native Americans residing in Florida. For these reasons, both Spain and the United States sought a mutually beneficial compromise with Florida at the heart of the deal.

Luis de Onís y Gonzalez was the Spanish Foreign Minister who negotiated the treaty. Arriving in Washington, D.C. in October 1809, he was not recognized as a legitimate government representative at first due to a civil war in Spain. It was not until December 1815 that the United States formally accepted Onís’ credentials. Although negotiations commenced under Secretary of State James Monroe (before he became the fifth president), most of the results occurred under Secretary of State John Quincy Adams (who would become the sixth president.) After the finer points were settled, the Adams-Onís Treaty accomplished two of the Unites States’ major priorities:

- Spain ceded Florida to the United States.

- The United States now claimed a solid, international boundary extending from the American South to the Pacific Northwest.

In order to coax these concessions from Spain, the United States relinquished any and all claim to Texas. Popular opinion considered it was far more advantageous for the United States to acquire Florida and a border that extended to the Pacific Ocean than it was to spread American influence to the Southwest. Melish’s map was cited specifically in the treaty as the used to determine the boundary lines. Although the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty immediately, members of the Spanish government hesitated. Spain hoped to use the unsigned treaty as leverage to prevent the United States from providing support to revolutionaries in the Spanish colonies. When Spain finally ratified the treaty in 1821, enough time had passed that it had to be ratified again by the U.S. Senate. Ironically, there were a number of Senators, particularly Henry Clay, who were reluctant to disavow American claims in Texas. Despite growing opposition, the treaty was officially ratified in 1821. Less than a year later, Mexico formally gained its independence from the Spanish Empire. A subsequent treaty ratified in 1832 by the United States and Mexico reaffirmed the border established by the Adams-Onís Treaty.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=937608.

Using the contours of John Melish’s map, the border followed three rivers: the Sabine River, the Red River, and the Arkansas River. However, disputes between states arose later on when it was discovered that Melish’s map was slightly incorrect. Stay tuned for Part 3 of the blog series to learn what these specific issues were and how they were reconciled.

Bibliography

Brooks, Philip C. Diplomacy and the Borderlands: The Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. New York: Octagon Books, 1970.

Stagg, J. C. A. Borderlines in Borderlands: James Madison and the Spanish-American Frontier, 1776-1821. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2009. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1npjn3.

Tyson, Carl N. The Red River in Southwestern History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.

No Comments