The general public often views a university as a place to cultivate knowledge and educate the young minds of today, but the student often has a different interpretation. As noted throughout Thelin’s history titled A History of American Higher Education (2011), students in the early to mid-twentieth century were drawn to and often enjoyed the social life offered as part of the “collegiate experience”. This social life included pranks, involvement in various student organizations, attendance at athletic events, and upon graduation there was often an improvement in social standing with respect to the general populace. By the 1940s the majority of the nation’s colleges and universities were coeducational, and many of the institutions had some form of an athletics program that orchestrated athletic events, which served as a social outlet for students and alumni to meet and mingle with one another. Since social activities, such as attending football games, had grown to become such an integral part of the student’s higher education experience, the analysis of changes in social demographics and campus-wide traditions seems most warranted. The term social demographics in this context refers to the social environment observed through a historical analysis of the campus via materials from the time period and from first-hand accounts of students.

In particular, the focus of this paper is the analysis of Baylor University in the 1940s. During this decade, the university inaugurated a new president, supported a student-led religious revival and experienced the effects of World War II. Based on the memoirs and oral histories provided by Baylor students from this time period, the era can be further subdivided into three distinct categories each marked by its unique set of observed effects on the university’s social demographics and campus wide traditions. The accounts of Ruby Florence Bruton Hewett (Hewett, 1976) and Katheryne Lucylle Cope Fulmer (Fulmer, 1:1-2, scrapbook) describe their experiences on the Baylor campus at the end of the Depression and prior to the university’s involvement in World War II efforts. Velma Ray Hugghins, a Baylor student from 1941 through 1945, provides a female’s perspective regarding life at Baylor during World War II in its entirety (Hugghins, 1982). John Sid Jones (Jones, 1998) and James M. Kendrick Jr. (Kendrick, 3-5) provide details of what the men faced as they left Baylor to join the war effort, and in the case of the former, John is able to describe his experience on the Baylor campus after he returned from World War II to continue on as a student (Jones, 1998). Billie Huggins Harrison offers a female’s perspective on campus life in a post-World War II era (Billie, Series 1). Based on analysis of their pasts, Baylor students’ higher education experiences were affected by wartime efforts and associated alterations to social demographics and campus-wide traditions during the 1940s.

Ruby Florence Bruton Hewett

Ruby Florence Bruton Hewett began her higher education experience at Wayland Baptist College in Plainview, Texas in 1933 and completed her first two years of college in 1935. Prior to entering Baylor University in 1937, she taught for two years at a country school named Hancock that was located in Dawson County, Texas. Ruby entered Baylor near the end of the Depression and lived in Burleson Annex. She described her dorm as being a relatively quiet place. Ruby recalled that “I was kind of a poor student and I could never afford their…snacks and things, so I didn’t participate much in that” (Hewett, 1976).

In an effort to cover her education and living expenses, Ruby worked on campus in Memorial dining hall where all of the meals were served family style. The female students would sit eight to a table, and the student workers would bring the food to each table (Hewett, 1976). After completing her first year at Baylor, Ruby began teaching at a school in Castro County during the academic year and attended Baylor during the summer where she again would work in the dining hall. During one of her summers, Ruby met a fellow student worker named Hector Ugharal from Puerto Rico. She described Hector as being distrusting of American women because based on personal experiences he believed that they were not faithful to their husbands and boyfriends. Ruby and Hector became friends that summer while working in the dining hall, and at the end of the term Ruby recalls Hector saying, “Well, Ruby, one thing about you, you have helped restore my confidence in American women” (Hewett, 1976). Although this recollection may appear as a simple anecdote, the memory actually conveys information about the campus culture and students’ perceptions of one another. Ruby noted that throughout her education at Baylor, she had the opportunity to interact with students from many different backgrounds and nationalities, and this was a new experience for her. The social exchange between students from different countries offered new perspectives and gave students a better understanding of how others may view their actions (Hewett, 1976).

Although she attended class and worked part-time on campus, Ruby still made time to interact with her peers. She joined the Y.W. A. (Young Women’s Auxiliary) and the BSU (Baptist Student Union). She described students during the late 1930’s and 1940 as being aware of what was right and wrong and thought the majority of students tried to emulate this knowledge in their actions (Hewett, 1976). Based on her recollections, there were students who enjoyed rebelling against authority, but they were small in number and President Neff quickly took care of any disturbances. Ruby enjoyed participating in the Y.W. A. and the BSU because the students involved with these organization shared beliefs similar to her own. Ruby also recalled campus wide social events, such as a spring festival, where nearly the entire student body would participate in “donkey races and three legged races” (Hewett, 1976). Through participation in student organizations and campus wide events, Ruby appeared to have connected with other students at the university. Baylor’s hosting of campus wide social events offered a platform for interacting with other students and developing a type of connection with the university as a whole.

Ruby’s experiences at Baylor between her arrival in 1937 and her graduation in 1940 provide a depiction of the campus as it transitioned out of the Depression and into the 1940s. Campus wide events, such as the spring festival, were available and enjoyed by many students, and the social demographics encouraged the interaction of students with various backgrounds and of different nationalities (Hewett, 1976). Ruby is an example of a student who was able to balance school, work and a social life while attending Baylor, but her experience reflects that of only a portion of the campus. Analysis of Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer’s Baylor experience during from 1939 to 1941 provides another view of campus life and traditions during the years leading up to World War II.

Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer

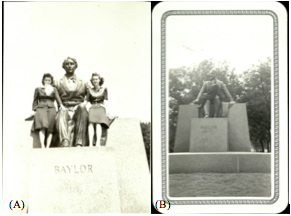

Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer attended Baylor as a student from 1939 to 1941 and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Speech. The scrapbook and photographs left by Katherine, which detail her experiences at Baylor University, depict her as the prototypical university student. She participated in various activities and student organizations across campus, and became close friends with several of her fellow classmates. As has become a tradition on campus, Katherine and her friends took several photographs (see Figure 1) with the Judge Baylor statue, including one while wearing her graduation cap and gown (Fulmer, 1:1-2, scrapbook).

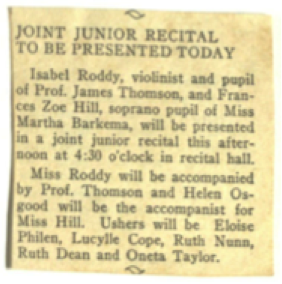

Katherine’s social experiences appear to have been well rounded as she participated in theater events, attended athletic events and spent time with her friends. Katherine did attend football games, which is evidenced by her keeping programs from the homecoming games that she attended in 1939 and 1940 that were played against TCU and Texas A&M, respectively. However, she also attended several musical performances and theater productions. During her senior year, she even served as an usher at one of the music recitals held on Baylor’s campus as seen in the newspaper clipping in Figure 2. She also visited the Browning room to observe the stunning display of artifacts secured in the Browning collection (Fulmer, 1:scrapbook).

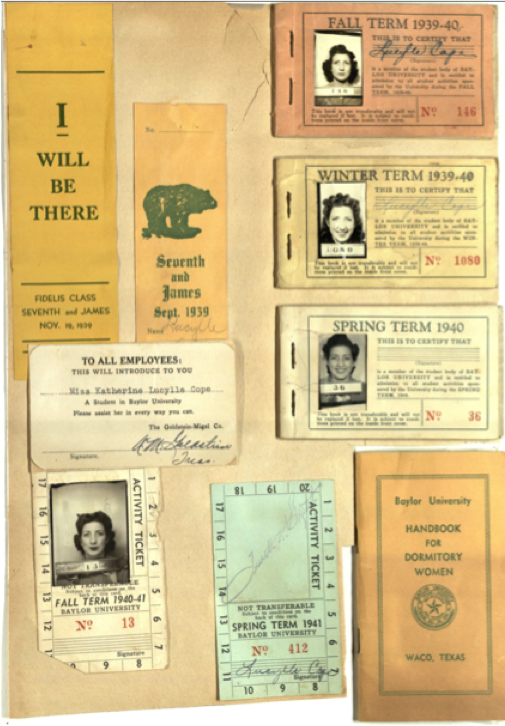

At this point in Baylor’s history, admittance to athletic events, subscriptions to the Baylor Lariat and access to many other amenities were provided by presenting your student identification card. In the 1939-1940 academic year, tickets were attached to the identification card, and each ticket could be redeemed for one event. In the 1940-1941 academic year, admittance to an event was provided via a hole punch on your student identification card. Each student was allowed a certain number of tickets or hole punches and received a new card each academic quarter as seen in the collection of Katherine’s identification and activity cards in Figure 3 (Fulmer, 1:scrapbook). While the reason for a limited number of activity passes is not known for certain, it may be suggested that the school wanted to limit the activities, so that the students would not neglect their schoolwork.

Throughout the photographs preserved by Katherine, the social interaction between students is clearly recognizable. Although she preserved a few photographs of her and her friends performing their obligatory studious activities, the majority captures the human and social interaction aspects of her college years. Figure 4 includes some examples of this social interaction with photographs taken while playing on grassy fields with other friends, meeting at the local ‘hangout’, dressing up for formal events and preparing for skits with costumes (Fulmer 1:1-2 1939-1941).

Through her careful preservation of photographs and programs obtained throughout her collegiate career at Baylor, Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer exhibited her passion toward Baylor and clearly indicated how much those experiences with friends meant to her. Her involvement in theater productions, attendance at football games, and membership in Baylor social clubs, such as the Red Head Club, indicates that during her time at Baylor Katherine voluntarily integrated herself into the campus culture and took part in campus wide traditions (Fulmer 1:scrapbook).

Upon analyzing the contents of the scrapbook and scenes depicted in additional photographs, the importance of social interactions with both female and male students and participation in Baylor traditions, such as Homecoming, in Katherine’s academic and personal development becomes clear. These events not only contributed to Katherine’s collegiate experience, but they helped prepare her for the world by making sure that she was well rounded in her interests. She was not a person who sat in the library and studied all day, but rather she experienced life outside of the classroom. She learned how to interact with other people in various settings. The description of both Ruby Florence Bruton Hewitt and Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer’s experiences as Baylor students highlight student experiences in the period leading up to World War II. Many of the characteristics of the social demographic and campus wide traditions echo what is observed across campus today, but these characteristics differ greatly from those that define the campus throughout the rest of the 1940s.

Velma Ray Hugghins

Although Ruby and Katherine’s experiences described student life prior to World War II, the effects of changes to the social demographic on campus and to university wide traditions have not yet been discussed. Analysis of the Baylor student experiences described in the memoirs of Velma Ray Hugghins, James M. Kendrick Jr. and John Sid Jones details how World War II affected the Baylor campus and the social dynamics between the students.

Velma Ray Hugghins attended Baylor from 1941 until 1945 and experienced the Baylor campus as it changed throughout the entire second World War. Velma majored in English during her undergraduate studies before pursuing a graduate degree under the watchful eyes of Dr. Armstrong and Dr. Smith (Hugghins, 1982). During her first semester as a Baylor student, Pearl Harbor was bombed, and people across campus began to change. She recalls that men knew they would eventually be leaving campus to assist in the war efforts and there was uncertainty regarding who would be alive and able to make return to Baylor after the war (Hugghins, 1982).

During World War II, Baylor opened its campus to army and navy personnel. These new students attended class, although not with Baylor students, and performed their drills and duties in the open areas across campus. Religion took center stage on campus as female students prayed for their fathers, brothers, fiancés and/or boyfriends who were fighting overseas. Similarly, male students who were awaiting to hear their orders or who received an early release from the armed forces found themselves putting a greater emphasis on their spiritual life rather than their social life or the campus traditions (Hugghins, 1982).

Velma was a member of the Baptist Student Union (BSU) at Baylor, and at the end of her sophomore year the nomination committee asked if she would serve as co-president with Tom Johnson, a sophomore student athlete. This invitation was highly unusual as the presidency was typically reserved for senior BSU members. Furthermore, the chances were high that Tom would be assisting the armed forces during that next year. In fact, Tom was called to duty the following year, and Velma served as the first female, acting president of the Baylor BSU during her junior year. Her introduction to the organization during her freshman year was unique in that her hometown church asked her to give a speech about her experiences with the BSU when she returned home at Christmas. At the time, she did not know what the BSU was or what the organization did. She was surprised to find out that every Baptist student was automatically a member of the BSU when they entered Baylor, and during her presidency she sought to clarify this for other students (Hugghins, 1982).

In addition to her role as the BSU president, Velma was also the managing editor of the 1944-1945 Centennial Round-Up annual which marked the 100th anniversary of the founding of Baylor University (Hugghins, 1982 and Garrett, Jr., 1945). By serving in such prominent roles in student organizations on campus, Velma’s experience suggests that female students were more likely to acquire leadership roles that were often held by male students prior to World War II. Although this time period was an excellent opportunity for female students to gain experience in leadership positions and develop skills in areas which were considered male-dominated prior to World War II, the absence of male students on campus directly affected the social dynamics of the student body. Their absence caused a void within the student social dynamics with the lack of football games, empty leadership positions within student organizations that needed to be filled, and the decrease in the number of coeducational social gatherings, such as formals and dates (Hugghins, 1982). While Velma’s memoirs describe Baylor’s campus during this time period, the accounts of both James M. Kendrick Jr. and John Sid Jones describe some of the experiences that male Baylor students had during the World War II years.

James M. Kendrick Jr.

The preceding sections have established the importance of social interactions between students and participation in university wide traditions, such as homecoming, in regard to a student’s development during his higher education experience. Analysis of letters written to James M. Kendrick Jr. from fellow students at Baylor University during this time period sheds light onto how such changes affected the students.

Student Experiences at Baylor: 1939-1943

James entered Baylor in 1939 and graduated with a Bachelors of Business Administration in 1943 (Kendrick, 5:11, 19). As a student, he was invited to participate in several student organizations (Kendrick, 5:1-2), and he became a member of the Baylor Chamber of Commerce (an organization on campus whose goal is “to preserve and protect the traditions of Baylor University”, such as Homecoming and caring for the live mascot (Chamber 2015)) in 1941 (Kendrick, 5:20). Like Katherine, James attended a variety of music and theater productions held on campus, and he also attended several programs hosted by the Civic Music Association (Kendrick, 5:23, 27).

Based on the number of letters he received and the content of these letters, James was a very social person. He received mail from students at Baylor as well as students attending universities in other states. For example, he was friends with Jane and Louise who attended Stephens (a women’s college) and Christian College, respectively, both located in Columbia, Missouri (Kendrick, 3:9). Throughout the letters, his friends recall their enjoyment of picnics, dances, and the latest events. In the early 1940s he even exchanged a letter with a friend from Texas A&M discussing which school would claim victory at their next game (Kendrick, 3:3). In November 1941, James and his family encountered a most unfortunate experience when James’ father passed away. In the wake of this event, James received numerous sympathy cards filled with words of condolence (Kendrick, 3:2).

As time progressed to 1943 and World War II had started, James began receiving mail from friends who had joined the war effort. In general, his friends did not choose or get drafted to any one particular branch of the armed forces, but rather they were spread across the Army, Navy, Air Force and the Marine Corps (Kendrick, 3). James joined the Army and reported for duty on May 20, 1943 (Kendrick, 3:18). That same year, Baylor University moved the graduation date from the intended day of May 31, 1943 to May 9, 1943 (Kendrick, 5:3). This alteration to the graduation ceremony was likely to accommodate those graduates who would be reporting for duty across the nation later that month. Furthermore, the change in date also suggests that the number of students (and possibly faculty) who were joining the armed forces was large enough to warrant such a significant change in the intended academic schedule. Although James left the Baylor campus in 1943, he was not yet finished with his Baylor experiences.

Changes on the Baylor Campus

Although students left Baylor to assist with the war effort, there were students who remained on campus, and their experiences were detailed in letters written to James while he was serving in the Army. The letters he received were primarily from female classmates and friends, but he also received some from male students who remained on campus (Kendrick, 3,4). These letters from classmates shed light on the changes in the social environment and university traditions during that time. Based on their descriptions, the effect these events were having on some members of the Baylor student body was significant.

In a letter from James’ friend Virgil postmarked July 6, 1943 he describes the state of Baylor’s campus as,

Baylor is dead…there’s no one here and nothing to do if anyone was here, so you can imagine what a lousy time we are having. I do not as yet know when or where I will be going, but I hope that it is soon and far. The army and the navy have taken over here, as you know, and it gives one a strange feeling to find Burleson full of naval cadets and Brooks full of army men. (Kendrick, 3:21)

From this letter, the presence of cadets and army members on campus had a significant impact on student life. The tone of Virgil’s letter indicates that students feel as though the soldiers are encroaching upon their territory at Baylor. Although the rest of Virgil’s letter indicates that students are ready to assist with the war effort, the social demographic across campus has changed with the presence of the soldiers and altered social life across campus (Kendrick, 3:21). These sentiments were felt not only by male students, but also by female students. In a letter postmarked June 11, 1943 from James’ friend Lucille, she states:

Well, you wouldn’t recognize Baylor now. Soldiers here, soldiers there, soldiers everywhere. Really, it seems so funny to see them marching to their classes everyday. It seems to me that there are just millions of them. You were right when you said that college life would never be the same again. (Kendrick, 3:17)

Lucille’s account of the Baylor social dynamic during this time period reaffirms that which was suggested by Virgil. The campus environment had changed. There was now a considerable portion of the campus population that was new and foreign to the Baylor students. In a June 23, 1943 letter from Mary, James is told that female students “aren’t allowed in town Sat. after 7:30 without a date. These wolves are really getting out of hand” (Kendrick, 3:16). The “wolves” to which Mary is referring are soldiers who are staying on the Baylor campus. Mary’s letter provides another example of how the presence of these soldiers was affecting student life and social interactions on campus.

James even received postcards from his Aunt Clara updating him on how his family members were doing. Each of the postcards she sent had an image from Baylor or somewhere noteworthy in Waco (like Cameron Park), and an image of one of the postcards is provided in Figure 5. Throughout her postcards Aunt Clara made sure James knew his family was doing well and was thinking of him (Kendrick 4:36).

The letters James received from friends and classmates outlined the changes in the social dynamics, but analysis of the Baylor Round-Up annuals indicate that some of the beloved campus traditions were not occurring during the World War II years. For example, in the 1942-1943 Round-Up, the only two sports that were mentioned were football and basketball (Heard, 1943). The rest of the athletic teams had been cancelled during the war. The football and basketball teams were soon to follow suit. In the 1943-1944 academic year, neither football nor basketball was played at Baylor (Wood, 1944). This trend continued through the 1944-1945 academic year (Garrett Jr., 1945), and sports began to be reintroduced to Baylor’s campus in the 1945-1946 academic year (Box, 1946).

Although football and basketball were again being played on Baylor’s campus in 1945, Homecoming did not occur until the 1946 football season because “neither President Neff nor the faculty members felt that it would be appropriate to name any day this year … “home-coming” due to the fact that so many Baylor men are still overseas” (Lariat, 47(7), pp. 1). This did not prevent a “football queen” from being announced that year (Box, 1946). During the 1946-1947 academic year, the tradition of Homecoming came back to campus and was one of the largest football events held to that date with 19,000 people in attendance (Lariat, 48(12), pp. 1).

As evidenced by the letters James M. Kendrick Jr. received from classmates and friends while in the Army, the social aspects of Baylor’s campus changed dramatically during World War II, and left students with an uneasy feeling as their typical social gatherings occurred less often and with fewer people (especially male students) as compared with pre-war times. From analysis of Baylor Round-Ups and Lariats during the war years, one can observe that campus traditions, such as Homecoming, were cancelled during the war years, and this is likely for two reasons. First, the university’s cancelling of a joyous, celebratory event shows respect for the armed forces as well as the impact on the campus of losing all but approximately one hundred of their male students (Jones, 1998). Second, since the nation was at war, money spent on events such as Homecoming would have been viewed as frivolous (even if the university had the money to spend). The letters written to James provide excellent examples of the social changes occurring on Baylor’s campus during this time in history, and an analysis of John Sid Jones’ oral memoirs will provide a firsthand account of a male student’s perspective of the Baylor campus upon returning from service in World War II (Jones, 1998).

John Sid Jones

In his memoirs John Sid Jones describes his personal experience as a Baylor student who left campus halfway through his undergraduate studies, served his country in the war effort, and returned to Baylor after the war to finish his degree. John’s family had close ties with Baylor University before he ever stepped foot on the campus. Both of John’s parents and his paternal aunt graduated from Baylor University in 1915 and 1916. John’s uncle, Sid Williams Jones, was planning to attend Baylor University before being fatally injured during a football practice while attending prep school at Burleson. After his passing, John’s grandfather established a scholarship in honor of Sid Williams Jones at Baylor University, and Baylor students continued using this scholarship for over 80 years (Jones, 1998).

John and his family began attending Baylor homecoming events during the 1930’s and enjoyed participating in such an exciting institutional and family tradition. John entered Baylor University in January 1943, but due to World War II efforts, he did not get to experience his first Baylor homecoming as a student until 1946. With the majority of the male students on campus either volunteering or being called to serve during World War II, Baylor’s football program was not operational during the 1943 and 1944 seasons (Jones, 1998). Even though the war had ended at the beginning of the 1945 school year, homecoming was not held during that year since many of the male students were still not yet home. John Sid Jones was one of the students who had not yet arrived back home. He entered the naval service after completing the 1944 spring term and returned to Baylor during the summer term of 1946 (Jones, 1998).

Prior to leaving campus in 1944, John completed as many classes toward his pre-med degree as he could fit into his schedule. He recalled that his first room assignment was in Brooks dormitory, but as Baylor began making room for army and navy personnel on campus during the spring of 1943, John and many of his male classmates were sent to various housing accommodations, some of which were located off campus. The following year Baylor students did not attend classes or have much interaction with the servicemen stationed at Baylor. The total number of Baylor students was reduced to approximately 900 female students and 100 male students by May 1944 (Jones, 1998).

With several of his family members having attended Baylor before him, John was aware of what Baylor had been like prior to World War II and noted that his experience was different from that of his family members. Nearly all of the Baylor students during this time period knew each other because the campus population had dwindled with the male students serving in war (Jones, 1998). John did participate in student organizations and attended BSU events while Velma Ray Hugghins was president before he left for service. While John was overseas, he exchanged letters with a female friend at Baylor who kept him apprised on events occurring around campus (Jones, 1998).

John returned to the Baylor campus during the summer session in 1946 and noted that many of the female students who had been at Baylor with him before the war had graduated, and the male students were returning to campus. Compared to when he left in 1944, John stated that the student population had grown from approximately 1,000 students to nearly 4,000 students. Although the end of World War II brought Baylor students back to campus, there was also an influx of new male students who used the GI bill to pay for their college tuition (Jones, 1998). These students grew up during the Depression in the 1930’s and in many cases neither they nor their family had the means to pay for a college education. For their service in the armed forces, the United States government was affording these young men an opportunity to obtain a higher level of education (Jones, 1998).

The influx of male students in a post-World War II era again changed the social dynamics and traditions across the Baylor campus. Beloved traditions, such as homecoming, were again taking place, and male students were again available to fulfill the leadership positions within many of the student organizations on campus. Like James M. Kendrick Jr., John was also a member of the Baylor Chamber of Commerce and strove to protect Baylor’s traditions after he returned from the war (Jones, 1998). Even though campus life appeared to be returning to what students considered the “norm” in a pre-World War II campus setting, the experiences and memories of these students were different from those of their predecessors and ultimately shaped their thoughts and actions. For example, after the male students returned from service, there was an increased focus on their faith and spiritual life (Jones, 1998 and Hugghins, 1982).

John Sid Jones provided a male student’s perspective of Baylor during and after World War II and analysis of his experiences shows how the campus changed during that time period with respect to the social dynamic amongst students and university wide traditions. Billie Ruth Huggins Harrison’s Baylor experiences provide a female’s point of view regarding the campus in its post-World War II years.

Billie Ruth Huggins Harrison

Billie Ruth Huggins Harrison attended Temple Junior College prior to arriving at Baylor in 1945. Similar to Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer, Billie’s social interests were well rounded and diverse. She attended music and theater events held in Waco Hall including events held by the Waco Symphony. Her first semester at Baylor, Billie was invited to participate in nearly a dozen student organizations and kept the invitation for each event. Although not always the case, people typically keep such items only if they have an emotional tie to the object in question. Thus, her taking the time to scrapbook such mementos likely indicates that she treasured the memory of at least being invited to such social events. Ultimately, she did join Phi Gamma Nu, a national society for businesswomen, which is fitting because she graduated with a Bachelors of Business Administration in 1947 (Billie, Series 1).

While she was attending Temple Junior College, Billie attended some football games at other universities (Billie, Series 1). Baylor University, which is one of the largest universities close to Temple, did not have any football during the 1943 or 1944 seasons as previously described (Wood, 1944 and Garrett Jr., 1945). So, instead of attending Baylor football games, Billie attended the annual rivalry match of the University of Texas and Texas A&M. She kept the programs from each of these games, and each of these two years the program cover contained a patriotic image as seen in Figure 6 (Billie, Series 1). Although the University of Texas and Texas A&M did continue to play football during the war years, they paid tribute to those serving their country by gestures such as including those photographs on the cover of their programs. This act reflects the impact that the war had on all colleges and universities throughout the country, not just at Baylor.

By 1945, football was reintroduced to the Baylor campus, and Billie attended what was originally supposed to be the Homecoming game against Southern Methodist University until President Neff and faculty members canceled the Homecoming events (Billie, Series 1 and Lariat, 47(7), pp. 1). A photograph of the program cover from this game is provided in Figure 7 (Billie, Series 1). Billie was also able to attend the 1946 Homecoming event, which was the first official Homecoming after World War II. The spectacle attracted a huge crowd of students and alumni as people sought to interact with one another after the war (Billie, Series 1 and Lariat, 48(12)).

Analysis of Billie’s memorabilia associated with her time as a Baylor student from 1945 to 1947 suggests that her experiences were not that much different than Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer’s experiences. However, the characteristics of the student population were markedly different during Billie’s college years as compared to that of Katherine Lucylle Cope Fulmer’s college years. As mentioned in the analysis of John Sid Jones’ memoirs, the changes in the student population after World War II were caused in part by the influx of male students who were using the GI bill to pay for their college education (Jones, 1998). Additionally, in the post-World War II era, each student on the Baylor campus brought a unique set of wartime memories and personal losses to the campus which shaped their actions and beliefs. Since Billie was interested in a variety of extracurricular areas, such as music and theater, the absence of athletic events did not appear to hamper her social growth and experiences, but the changes in the social dynamics across campus surely had an impact on her maturation process while at Baylor. The soldiers that were on campus during the war were no longer there, so their lack of presence brought back a sense of familiarity between students on campus. By the last year of Billie’s Baylor experience, Baylor athletic traditions and the social demographic on campus was similar to what it had been prior to World War II, but the effects of the war had left an indelible mark on the lives of students who lived during that event (Billie, Series 1).

Conclusion

Baylor’s athletic traditions and the social makeup of the campus changed dramatically during the 1940s. Analysis of the undergraduate experiences described by six Baylor students during this era shed light on how the student body and their collective experiences changed throughout the decade. Through a comparison of these students’ experiences, three distinct student populations were identified and described in detail. The first group of students in this era arrived at Baylor near the end of the Depression but before World War II affected the campus. These students enjoyed traditional university-wide events, such as homecoming and spring festival (Fulmer, 1:scrapbook and Hewett, 1976), and joined various student organizations, such as the Red Head Club (Fulmer, 1:scrapbook). The second type of student population was characterized by their Baylor experiences during World War II when the male students left campus and servicemen arrived on campus. The social dynamics amongst students, the student organizations and the university-wide traditions all experienced changes during this time period (Kendrick 3-5, Hugghins, 1986 and Jones 1998). The characteristics of the third student population during this time period were marked by the students’ wartime experiences. This group of students saw a rapid increase in the number of male students as they returned home from war and began integrating back into campus life (Jones, 1998 and Billie, Series 1). Analysis of these three groups has shown that changes to a university’s social climate and alterations to or the absence of campus-wide traditions do affect a student’s higher education experience.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1356113. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Author’s Note

While referring to archival sources in the text, the following citation format is used (source name, Box#: Folder#(s)).

References

Billie Huggins Harrison Papers, Accession #3906, Series 1, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Box, E. (Ed.). (1946). The 1946 Round-Up (Vol. 45). Waco, TX: The Students of Baylor University. Collection: Baylor University Annuals – The “Round-Up”.

Fulmer, Katherine Lucylle Cope, Accession #BU/375, Box 1, Folder 1, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Fulmer, Katherine Lucylle Cope, Accession #BU/375, Box 1, Folder 2, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Fulmer, Katherine Lucylle Cope, Accession #BU/375, Box 1, Scrapbook, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Garrett Jr., J.L. (Ed.). (1945). Centennial Round-Up (Vol. 44). Waco, TX: The Students of Baylor University. Collection: Baylor University Annuals – The “Round-Up”.

Heard, D. (Ed.). (1943). Nineteen Hundred and Forty-three Round-Up (Vol. 42). Waco, TX: The Students of Baylor University. Collection: Baylor University Annuals – The “Round-Up”.

Hewett, R. F. B. (Interviewee) and Owens, N. E. (Interviewer). (July 7-28, 1976). Oral History Memoir: Texas Baptist Oral History Consortium. Baylor University Institute for Oral History, Baylor University.

Hugghins, V. R. (Interviewee), Cook, L. K. (Interviewer) and Stokes, K. J. (Interviewer). (August 27, 1982). Oral History Memoir. Baylor University Institute for Oral History, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, Folder 2, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, Folder 3, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, Folder 9, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, Folder 16, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, Folder 17, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, Folder 18, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 3, Folder 21, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 4, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 4, Folder 36, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 1, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 2, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 3, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 11, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 19, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 20, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 23, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

James M. Kendrick Jr. Papers, Accession #2749, Box 5, Folder 27, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Jones, J. S. (Interviewee) and Myers, L. E. (Interviewer). (August 12-27, 1998). Oral History Memoir. Baylor University Institute for Oral History, Baylor University.

Thelin, J. R. (2011). A history of American higher education, 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins.

Wood, M.J. (Ed.). (1944). The 1944 Round-Up of Service (Vol. 43). Waco, TX: The Students of Baylor University. Collection: Baylor University Annuals – The “Round-Up”.

(1945) No homecoming. The Baylor Lariat, 47(7), pp. 1. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/34427/rec/1

(1946) University cleans up debris of largest homecoming: Football game draws 19,000. The Baylor Lariat, 48(12), pp. 1. http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/lariat/id/22206/rec/1

(2015) Baylor University website description of Baylor Chamber of Commerce (no author listed on website). http://www.baylor.edu/chamber/