Written by Melinda Creech, Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

James Russell Lowell was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor and diplomat associated with the Fireside Poets. The Fireside Poets, whose popularity rivaled English poets, used conventional meter, making the poems suitable for family reading by the fireside. Lowell and Elizabeth Barrett Browning corresponded, sharing volumes of poetry and an interest in anti-slavery issues. Later when Lowell visited in England and Europe, letters were exchanged with Robert Browning about their social engagements.

The Armstrong Browning Library’s holdings related to James Russell Lowell include twelve letters, one Elizabeth Barrett Browning manuscript of Lowell’s poems, and one previously unpublished manuscript poem by Lowell, and over seventy books, some rare.

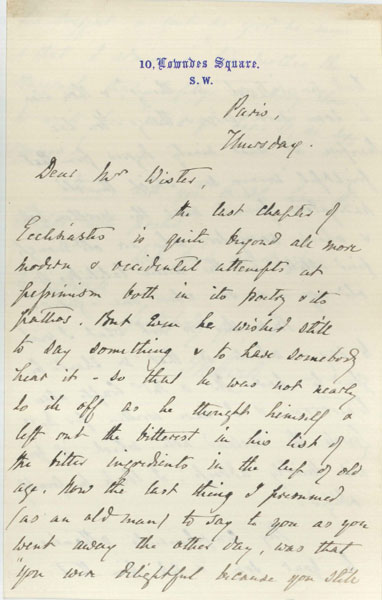

In this letter, addressed to the mother of Owen Wister, American author and “father” of Western fiction, Lowell apologizes for disparaging her age at their last meeting.

The last chapter of Ecclesiastes is quite beyond all more modern & occidental attempts as pessimism both in its poetry & its pathos. But even he wished still to say something & to have somebody hear it—so that he was not nearly so ill of as he thought himself & left out the bitterest in his list of the bitter ingredients in the leaf of old age. Now the last thing I presumed (as an old man) to say to you as you went away the other day, was that “you were delightful because you still took an interest in things, “…You are therefore at least ninety degrees from that frightful “wormy sea” which the old navigators found near the northern pole & which navigators who are old enough find still in the arctic latitudes of old age…

James Russell Lowell. “I asked of Echo: ‘what’s a good adviser?’” 03 July 1858.

This poem, written on the back of an envelope, has never been published.

I asked of Echo: “what’s a good advisor?”

And Echo answered confidently “I, sir!”

I called again & asked, “What then’s a mentor?”

And Echo answered straight, “a men-tormenter!”

Letter from James Russell Lowell to Frederic William Farrar. 7 May 1883.

In this letter to cleric and author F. W. Farrar, Lowell comments about how much he likes Tennyson’s verses.

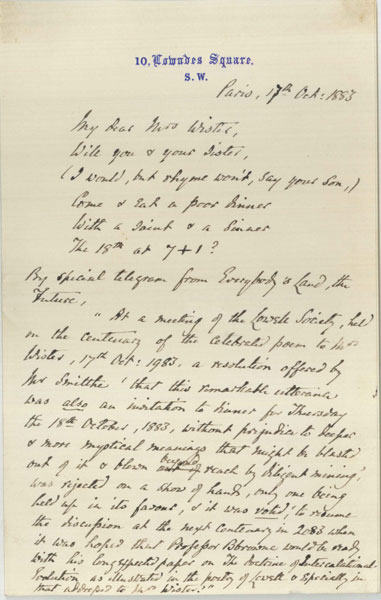

Letter from [James Russell Lowell] to Mrs. Wister [Owen’s mother]. 17 October 1883.

Lowell composes two humorous poems inviting Mrs. Wister to dinner.

My dear Mrs. Wister,

Will you & your sister,

(I would, but rhyme won’t, say your son.)

Come & eat a poor dinner

With a saint & a sinner

The 18th at 7 + 1?

P.S. ½ past 2.

My dear Mrs. Wister,

Yours burned like a blister

With pinpoints of “slow” & all that,

So, to prove I don’t tingle,

I send you some jingle

If possible ten times as flat.

If you can’t come on my day,

What say you to Friday?

The dinner will be quite as bad:

And, unless you’ve objections

To fastday reflections,

Come both, & make both of us glad!

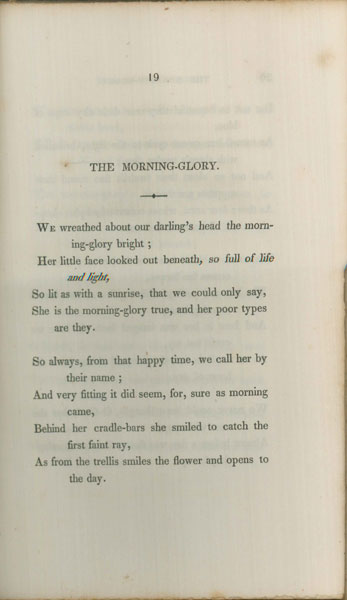

Felicia Hemans, James Russell Lowell, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, eds. Echoes of Infant Voices. Boston: Wm. Crosby and H. P. Nichols, 1849.

This rare first edition includes poems by Longfellow, Lowell, Emerson, Hemans, and Dickens.

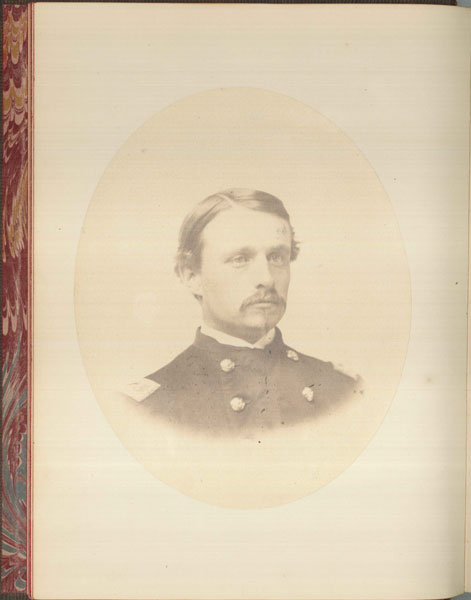

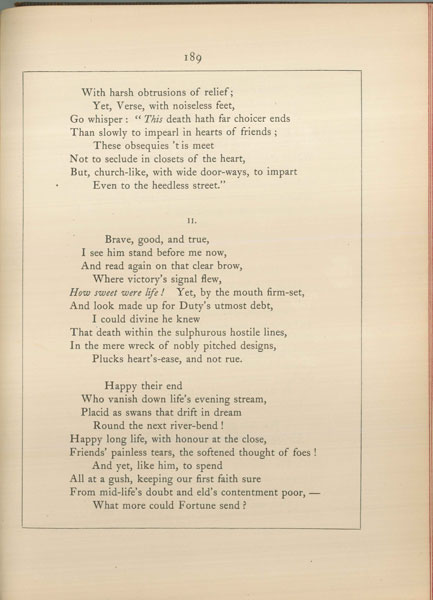

James Russell Lowell and Ralph Waldo Emerson, eds. Memorial, RGS. Cambridge: University Press, 1864.

This volume compiled in memory of Robert G. Shaw, contains extracts from Shaw’s letters and poems from Lowell, Emerson, and others. Shaw, an American military officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War, commanded the all-black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which entered the war in 1863. He was killed in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, near Charleston, South Carolina. He is the principal subject of the 1989 film Glory.

James Russell Lowell. Under the Willows: And Other Poems. Boston: Fields, Osgood, & Co, 1869.

This volume is a first edition. “Under the Willows,” the second poem in this collection and the poem from which the collection takes its name, is a paean to a willow tree in the month of June.