Idylls of the King. By Alfred Tennyson. Illustrated with thirty-seven engravings by Gustave Doré. London: Printed by Edward Moxon and Co., Dover Street, W (1868).

(ABLibrary 19thCent Jumbo Oversize PR5558.A2 1868)

Mid-January 1869 Alfred Tennyson to Frederick Locker ABL Digital Victorian Collection

Rare Item Analysis: Layers of Interpretation: Moxon’s Illustrated Idylls of the King in Context

by Andrew Hicks

Click here to visit an interactive timeline and map related to this post on Central Online Victorian Educator (COVE).

Edward Moxon and Co.’s illustrated 1868 edition of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, located in the Armstrong Browning Library’s Oversize collection, is an ornate volume outside and in. The book’s large size suggests that it should be displayed in the home, and the gilded edges of the pages complement the bright reds and golds of the cover, on which four shields bearing the titles of the four collected idylls surround the central image of a golden dragon. The book contains the text of the four idylls published to that time: “Enid,” “Elaine,” “Vivien,” and “Guinevere,” first published together in 1859, and then released in separate illustrated editions before being recollected here. Each is illustrated with engravings by the French artist Gustave Doré.

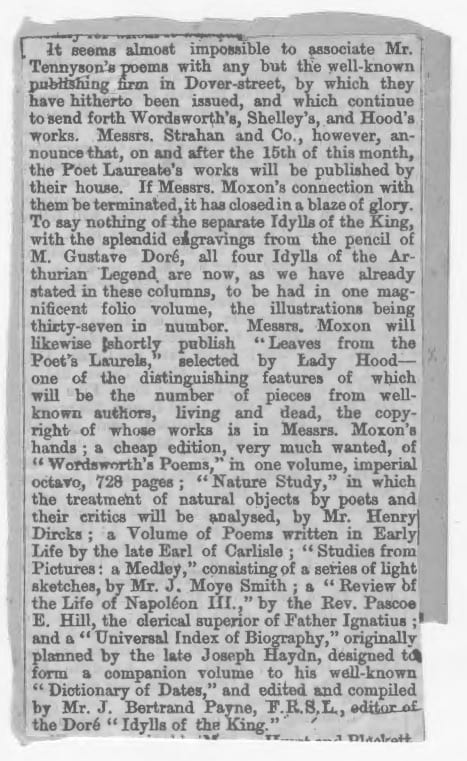

The Armstrong Browning Library’s Victorian Collection also contains a letter concerning this edition sent from Tennyson to his friend the poet Frederick Locker. The letter is dated from mid-January of 1869 and includes a clipping from the Daily Telegraph praising the edition and celebrating a triumphant close to Tennyson’s long relationship with Moxon as a publisher, which would end after this volume. The contents of Tennyson’s letter, however, indicate a less triumphant narrative surrounding this edition of Idylls of the King. Considering these two items together helps us to answer two primary questions: How does this volume, through its illustration and presentation, interpret Tennyson’s Idylls in light of Christian scripture and British literary history? Additionally, how does contextual information, including Tennyson’s correspondence, highlight the struggles, tensions, and ambiguities of this project?

To examine this volume through the lens of Christian scripture and British literary history is in keeping with a notable critical conversation surrounding Idylls of the King. Framing his reading within the context of the emergence of the higher criticism of the Bible, Charles LaPorte argues that Idylls “presents Tennyson’s most arduous intervention into the Victorians’ changing understanding of scripture” through “an appeal to religious affect” that is “grounded in culture” (68). Tennyson, according to LaPorte, guided by his belief “in the virtues of a shared national religion…frames Arthurian legend in the Idylls in such a way as to construct for the Bible a local, parallel instance of poetic inspiration” (69). According to this reading, Tennyson seeks with the Idylls to offer a national scripture that parallels the Bible while being framed through the lens of British myth, history, and poetry.

In this light, the format of the Moxon edition suggests parallels to similar modes of presenting Christian scripture already at play in Victorian society. One example is the popularity of “Family Bibles”—large, ornately decorated and illustrated Bibles that, according to Mary Wilson Carpenter, “were published in many different editions from the early eighteenth century through the late nineteenth century” and had the “heyday of their publication…[in] the Victorian era” (“From Treasures” 116). Elsewhere, Carpenter examines an illustration accompanying the story of Noah in one Family Bible, highlighting the illustration’s interpretation of the story to reinforce popular notions of “order…hierarchy…and the balance of sexual difference” (Imperial Bibles 16). Although a sustained examination of Family Bibles alongside Moxon’s illustrated Idylls would demonstrate certain differences between the projects, this connection to the Family Bible as Carpenter portrays it highlights an important feature of the Moxon edition. In addition to being a large decorative volume, Moxon’s Idylls uses illustration to interpret the text. In this edition the text is interpreted in light of Christian scripture and British literary history through the engravings of Gustave Doré.

Doré’s is primarily remembered as the illustrator of several classics of international literature, including the works of Rabelais and Balzac, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and Cervantes’s Don Quixote. If it seems initially odd that a text of such distinctly British national character would be illustrated by a French artist with a widely European body of work, it should be noted that Doré had a particular relationship to and investment in England, specifically the city of London. Doré enjoyed particular fame in London, with a popular gallery on Bond Street. In 1872, a few years after the publication of the illustrated Idylls, Doré collaborated with the journalist William Blanchard Jerrold on the volume London: A Pilgrimage, which highlights the effects of economic inequality in the city. He would also illustrate Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and had unfulfilled ambitions to illustrate the works of Shakespeare (“Gustave Doré”).

The most immediately relevant context for Doré’s illustrations of Idylls of the King, however, comes from his illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost and of the Bible. Both sets are dated 1866, shortly before the publication of Moxon’s edition. Juxtaposing Doré’s engravings from Idylls of the King with his illustrations from these other two works helps to establish the ways in which Moxon’s edition interprets Tennyson’s work through the lens of Christian scripture and British literary history. As a point of focus, I will here consider selections from Doré’s illustrations of “Vivien” alongside selections from Paradise Lost and the Bible. All images mentioned are included in the PowerPoint that accompanies this post.

In Tennyson’s “Vivien” (cited here according to its later appearance as “Merlin and Vivien”), Vivien tempts Merlin to reveal to her a charm that she will use to imprison him. Merlin makes reference to the Genesis narrative of the Fall in his resistance to this temptation: “Too much I trusted when I told you [of the charm], / And stirred this vice in you which ruined man / Through woman the first hour” (359-361). Doré’s illustrations seem to capitalize on this reference by interpreting the idyll as an echo of the Fall narrative. This can be observed in the notable ways in which these engravings echo his illustrations of Eden in Paradise Lost and the Bible, though with important contrasts.

The opening engraving for “Vivien” (Slide 2 of the PowerPoint) depicts Merlin and Vivien in an intimate embrace beneath a large tree in a forest, striking a visual parallel to similar depictions of Adam and Eve from the Paradise Lost set (Slides 3 and 4). Certain details, however, complicate the parallel to Eden. Tennyson repeatedly employs serpent imagery to cast Vivien as a tempter, and Doré’s illustration echoes this imagery in the serpentine rendering of the trees’ roots and branches and the way in which Vivien’s pose mirrors this shape through the twisting of her body. The Edenic intimacy of Doré’s illustrations of Milton is recast here as a false intimacy and a vehicle for temptation. A similar contrastive echo is observable between the final engraving of “Vivien” (Slide 5) and Doré’s illustration of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden from the Bible (Slide 6). Both scenes are dark but illuminated by a faint light (the Eden image by the light shining on the angel, and the Arthurian image by a flash of lightning in the upper right corner). Strikingly, both images feature a figure or figures moving away to the right from a central point, and in both images a figure is looking back to that central point. There is an important contrast, however, in the identities of the figures themselves. In the Eden image Adam and Eve move together away from the angel that now guards the Garden, still intimately embracing, with Adam looking back over his shoulder in dejected longing. In the image from “Vivien,” Vivien moves alone away from the cursed Merlin, looking back over her shoulder in triumph. If “Vivien” is here interpreted as an echo of the Fall, then, it is a new narrative of the Fall with its own implications. Although humanity is expelled from the Garden in the biblical narrative and illustration, the tempting serpent is punished, and man and woman remain bound together in intimate solidarity. By contrast, in the illustration from Idylls the tempter is triumphant, and the intimate solidarity between man and woman is sundered through the identification of the woman with the tempter. This troubling conclusion highlights that while Doré’s illustrations from “Vivien” interpret the idyll through the lens of the biblical and Miltonic narratives of the Fall, these narratives are themselves modified and interpreted through this process.

There is a more direct parallel between Doré’s engraving of the founding of the Round Table (Slide 7), also from “Vivien,” and his illustration of the Last Supper from the biblical set (Slide 8). The centrality of Arthur in the former image mirrors the centrality of Christ in the latter, and the two images are united in depicting a group of figures gathered in various poses around a table and the significant presence of the chalice in each. This is a pointed example of what LaPorte identifies as a central feature of the Idylls: the “coupling of the figures of the mythical Arthur and the mythical Christ” (75). Within Tennyson’s project of framing his Idylls as “a local, parallel instance of poetic inspiration” (Laporte 69) to Christian scripture, this image directly establishes the crucial parallel between Arthur and Christ.

When viewed on its own, Moxon’s edition of Idylls of the King seems to be a successful collection of Tennyson’s idylls into a volume worthy of its literary and religious significance. Doré’s illustrations serve to connect the work to the scripture with which it is in conversation, while at the same time demonstrating the work’s reimagining of this scripture within British mythical and literary history. Tennyson’s letter to Frederick Locker from January of 1869, however, hints at the tension and ambivalence that attended this edition.

As previously mentioned, this letter includes a clipping from the Daily Telegraph praising the Moxon edition. Tennyson’s letter hints at a less triumphant story, however, especially in its treatment of James Bertrand Payne, manager of Moxon at the time and editor of the illustrated Idylls. Tennyson takes a sardonic tone when referencing Payne, seeming to mock the editor through comparison to Shakespeare’s Pistol (a self-important character from the Henry plays and The Merry Wives of Windsor), a comparison he would revisit in a later epigram (“Ancient Pistol, Peacock Payne”). Additionally, Tennyson includes a likely faux-reverential reference to the honorific F.R.S.L., indicating Payne’s status as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (though Tennyson seems to have inverted the ‘S’ and the ‘L’). It seems accurate that Payne’s self-aggrandizing influenced the illustrated Idylls, as his son verified that the editor used his own image as the model for Arthur in the front engraving (Cheshire 81).

The Telegraph clipping announces the severance of Tennyson’s relationship with Moxon, although the firm “had published his books for over thirty years” (Cheshire 67). Jim Cheshire asserts that this severance occurred at the end of long-brewing tensions between Tennyson and Payne, culminating in the publication process for this edition of Idylls. Payne was made manager of Moxon in 1864 by Emma Moxon, widow of the firm’s founder Edward Moxon (Cheshire 69), and immediately began implementing commercially aggressive tactics, including the increased production of elaborate illustrated editions marketed as expensive Christmas gifts (71-2). Tennyson was frustrated by the “commercial exploitation of [his] poetry” (67), and these frustrations only increased along with the poet’s disputes with Payne about a fair settlement on royalties for the illustrated Idylls. Tennyson’s letter to Locker, then, reveals the tensions at play between the volume’s assumed success and the poet’s conflictual relationship to its production.

A view of the wider context also demonstrates the mixed reception that Moxon’s Idylls received. Financially, the project proved detrimental to Moxon. Cheshire asserts that the assumption of the volume’s success was and is largely based on Payne’s overstated reports (68), and that the cost of the edition’s publication combined with its lower-than-expected sales contributed to Moxon’s decline (84). Although the illustrations were praised in many outlets (including The Spectator), others were more critical. The Musée d’Orsay reports, for instance, that some British readers “thought that the characters did not have sufficiently ‘English” features’ (“Gustave Doré”). It is easy to read into this response a certain nationalistic doubt that a French artist could properly render a distinctly British work. A review of “Vivien” and “Guinevere” (upon their publication in 1867, before the collected edition) from The Anathaeum similarly criticizes Doré’s interpretation of Tennyson’s work by speculating that “Dore has never read Tennyson, and has never thought of Tennyson while engaged upon this work” (qtd. in Cheshire 85). These critiques are grounded in the notion that textual illustrations are open to reinterpreting or misinterpreting the illustrated texts. This seems to be a concern that Tennyson shared. Cheshire highlights Tennyson’s misgivings about illustrated editions of his work, associating it with an anxiety about “the inevitable and necessary dislocation between word and image” (70) and the accompanying surrender of the author’s control when a text is handed over to be interpreted by an illustrator.

This concern over interpretation is telling in light of the layers of interpretation present in Moxon’s edition. Doré’s illustrations interpret Tennyson’s text, which is itself engaged in an interpretive relationship with Christian scripture. Although Tennyson’s letter to Locker seems fueled primarily by the poet’s fraught relationship with Payne, contextual information helps connect Tennyson’s ambivalence toward the volume to his misgivings over artistic interpretations of poetical works, including his own. In this way, these two rare items together illustrate two features of an ambitious project: the interpretation of Tennyson’s Idylls in light of Christian scripture and British literary history, and the tensions and ambiguities that attend this process. Although my analysis of Doré’s interpretive work is limited to a small selection of engravings from “Vivien,” the volume’s other illustrations would prove fertile ground for further work in assessing the scriptural and literary resonances of Doré’s interpretations. Additionally, the suggested connection to Victorian Family Bibles offers an avenue for further investigation into the significance of the format of Moxon’s illustrated Idylls. In these and other ways, these two items from the Armstrong Browning Library suggest further possibilities for future scholarship.

Accompanying PowerPoint: Layers of Interpretation

Works Cited

Carpenter, Mary Wilson. “From Treasures to Trash, or, the Real History of ‘Family Bibles.’” Constructing Nineteenth-Century Religion: Literary, Historical, and Religious Studies in Dialogue, edited by Joshua King and Winter Jade Werner, The Ohio State University Press, 2019, pp. 115-138.

—. Imperial Bibles, Domestic Bodies: Women, Sexuality, and Religion in the Victorian Market. Ohio University Press, 2003.

Cheshire, Jim. “The Fall of the House of Moxon: James Bertrand Payne and the Illustrated ‘Idylls of the King.’” Victorian Poetry, vol. 50, no. 1, 2012, pp. 67-90. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41698835.

“Gustave Doré: Master of Imagination.” Musée d’Orsay, 2014, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/events/exhibitions/archives/exhibitions-archives/page/0/article/gustave-dore-37172.html?cHash=19a00c278c. Accessed 4 October 2019.

Laporte, Charles. Victorian Poets and the Changing Bible. University of Virginia Press, 2011.

Tennyson, Alfred. “Ancient Pistol, Peacock Payne.” The Poems of Tennyson in Three Volumes: Volume Three, edited by Christopher Ricks, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1987, p. 11.

—. “Merlin and Vivien.” Tennyson: A Selected Edition, Revised Edition, edited by Christopher Ricks, Routledge, 2014, pp. 805-834.